The William Windham lunacy trial

About the book: 'Bring Him in Mad'

Wiliam Frederick Windham, the eccentric squire of Felbrigg Hall in Norfolk, was put through a public inquiry into his state of mind by his high-born relatives. They wanted to ‘bring him in mad’ because of his infatuation with Agnes Willoughby – a notorious young woman of the kind popularly known as ‘pretty horsebreakers’. Windham stood to lose both his freedom of action and the control of his property if found of unsound mind.

Reflecting on the case from his Edwardian old-age, fictional retired solicitor George Phinney tells the story of Windham and the events leading up to, and following, the trial.

Phinney’s memoir brings to life the principal characters involved in the case and charts the twists and turns of an affair that gripped public attention for weeks and caused a national sensation.

About the trial: Lunacy Commissions

Windham’s trial was technically a Commission De Lunatico Inquirendo. These were required when relatives sought to take control of a “supposed lunatic’s” property and person.

As Lunacy Commissions were part of a complex and expensive Chancery court procedure, they were comparatively rare and seldom contested. In the three years from July 1860 to June 1863 only 180 such cases were brought, of which Windham’s was one of only five contested before a jury.

Most were conducted quickly and quietly at country inns or asylums, and Windham’s was exceptional in the degree of popular and press attention it attracted. Lunacy Commissions declined after the introduction of the cheaper, simpler and more private ‘receivership’ procedure in 1891.

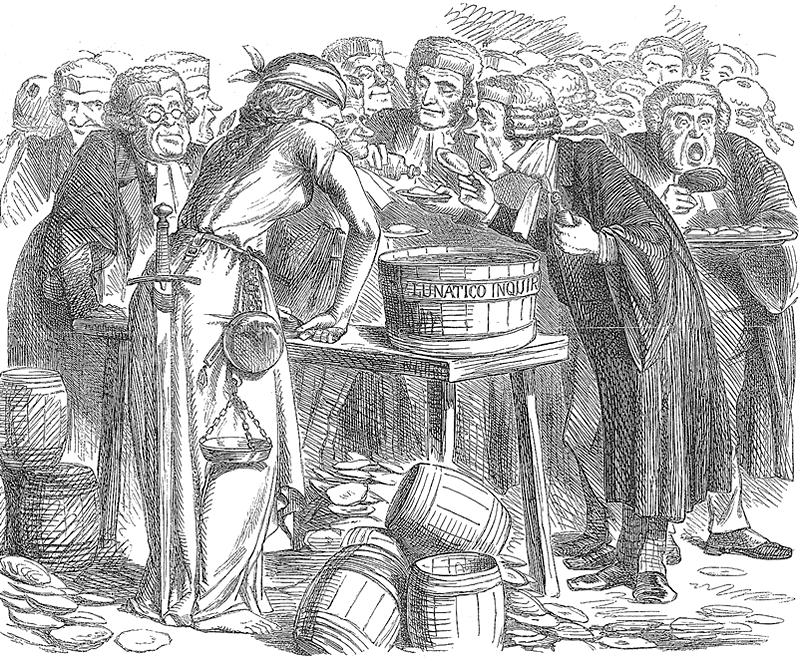

Windham’s case was heard before a packed courtroom, and was exhaustively covered and commented upon in the London dailies and the periodical press. In the end it turned itself into a kind of lunacy.

Punch published a cartoon of barristers eating oysters from a barrel with the caption: ‘Law and Lunacy, Or, A Glorious Oyster season for the Lawyers‘.

About the real characters

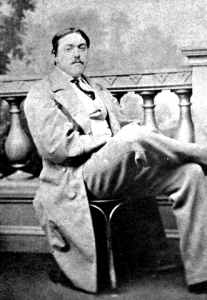

William Frederick Windham

Born an only child with a harelip, the heir to wealthy Felbrigg Hall in Norfolk endured a lonely and capricious upbringing. He developed an awkwardness of manner, and eccentricities – such as waiting at table, costumed in the Windham family livery. Later, he would dress as a railwayguard and work trains on the Eastern Counties Railway.

Born an only child with a harelip, the heir to wealthy Felbrigg Hall in Norfolk endured a lonely and capricious upbringing. He developed an awkwardness of manner, and eccentricities – such as waiting at table, costumed in the Windham family livery. Later, he would dress as a railwayguard and work trains on the Eastern Counties Railway.

His truculent father, William Howe Windham, died when he was aged only fourteen and his mother Lady Sophia, a daughter of the aristocratic Hervey family of Ickworth in Suffolk, remarried and consigned him to the care of various ill-suited, and sometimes brutal, ‘tutors’.

Agnes Willoughby

Unable to establish a rapport with suitable young women of his own class, Windham became fascinated with the ‘pretty horsebreaker’ Agnes Willoughby while he was boarding in London.

Unable to establish a rapport with suitable young women of his own class, Windham became fascinated with the ‘pretty horsebreaker’ Agnes Willoughby while he was boarding in London.

She was a low-born country girl who had risen rapidly to become a celebrated society courtesan by the age of twenty-one. She could be seen holding court from a fine carriage in Hyde Park, or viewing Italian opera from her own box.

Though incredulous on first hearing it, Agnes eventually accepted Windham’s marriage proposal. It did, after all, offer her the long-term security of becoming the Lady of Felbrigg Hall.

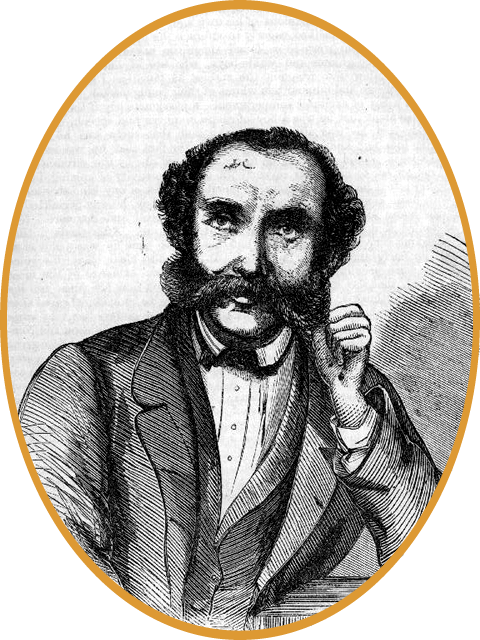

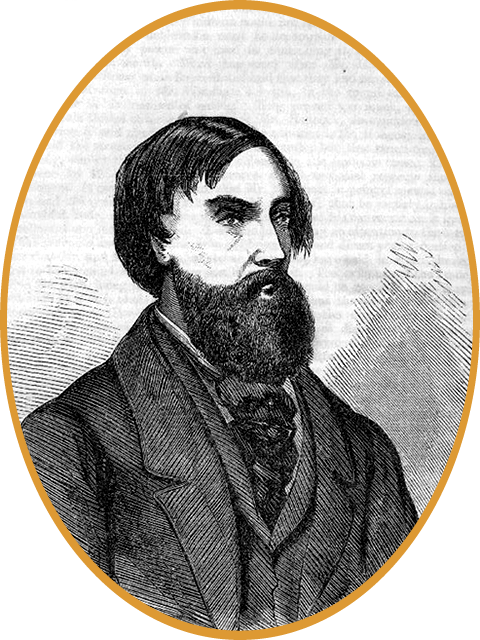

General Charles Ashe Windham

The military reputation of Windham’s Uncle Charles was made in the Crimean War when he was acclaimed ‘The Hero of the Redan’, but broken in the Indian Mutiny when his generalship was called into question.

The military reputation of Windham’s Uncle Charles was made in the Crimean War when he was acclaimed ‘The Hero of the Redan’, but broken in the Indian Mutiny when his generalship was called into question.

He tried, and failed, to stop his nephew’s marriage to Agnes Willoughby, which took place when William came into his inheritance on reaching twenty-one.

He then sought to have his nephew delared mad by a Lunacy Commission, to invalidate his marriage and take control of Felbrigg from him.

Many doubted the purity of the general’s motives, especially when he refused to be cross-examined at the trial.

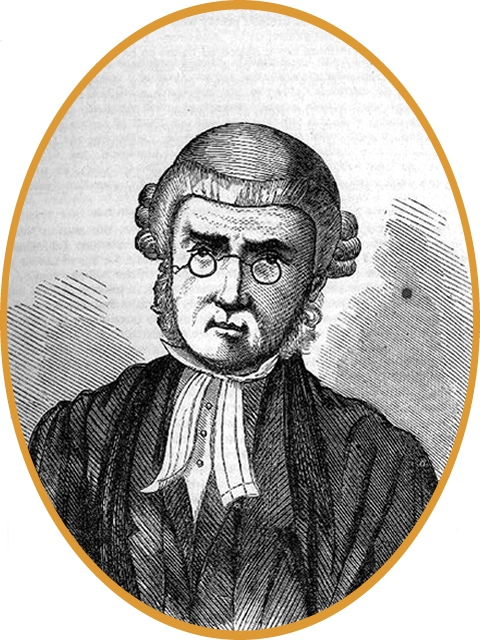

Montague Chambers QC

Distinguished barrister Montague Chambers led the case against Windham, which was brought by the general and fourteen other aunts and uncles who barely knew their nephew.

Distinguished barrister Montague Chambers led the case against Windham, which was brought by the general and fourteen other aunts and uncles who barely knew their nephew.

Windham’s mother, Lady Sophia, did not join in with the action but neither did she give evidence for her son.

Chambers produced numerous witnesses who swore to the “supposed lunatic’s” undoubted peculiarities from childhood.

Much of this was more comic than damning, but then he called some witnesses who swore to unspeakable doings on Windham’s part, including foul gluttony, murderous threats of violence, and indecent exposure.

Hugh Cairns QC

Austere Ulsterman, and rising Conservative politician, Sir Hugh Cairns was engaged to lead for the defence. He deployed his formidable forensic and oratorial skills to the full, but the defence team tried the court’s patience by putting up an endless procession of trivial witnesses testifying to Windham’s sanity.

Austere Ulsterman, and rising Conservative politician, Sir Hugh Cairns was engaged to lead for the defence. He deployed his formidable forensic and oratorial skills to the full, but the defence team tried the court’s patience by putting up an endless procession of trivial witnesses testifying to Windham’s sanity.

Sir Hugh, later the first Earl Cairns, was afterwards twice Lord Chancellor and a prominent lieutenant of Benjamin Disraeli’s.

He suffered a scandal of his own in 1884 when his son, Lord Garmoyle, was successfully sued for breach of promise to marry by the actress May Fortescue who won £10,000 in damages.

Samuel Warren QC

Coincidentally, the man who presided over the trial, ‘Master in Lunacy’ Samuel Warren QC, had earlier written a novel entitled Ten Thousand a Year about a legal case concerning a young heir. Warren had authored other literary works, like Diary of a Late Physician, that were popular in their day but have not stood the test of time owing to their overwrought prose and simplistic moralising.

Coincidentally, the man who presided over the trial, ‘Master in Lunacy’ Samuel Warren QC, had earlier written a novel entitled Ten Thousand a Year about a legal case concerning a young heir. Warren had authored other literary works, like Diary of a Late Physician, that were popular in their day but have not stood the test of time owing to their overwrought prose and simplistic moralising.

Because Lunacy Commissions were so rarely contested, the ‘Masters’ who tried them were not actual judges. Vain and vacilating, and lacking the experience to handle major proceedings conducted in the public eye, Warren allowed them to drown in a sea of irrelevancy.

Dr Forbes Benignus Winslow

Winslow was the principal ‘alienist’, or ‘mad-doctor’ as psychiatric practitioners were then often known, put up against Windham.

Winslow was the principal ‘alienist’, or ‘mad-doctor’ as psychiatric practitioners were then often known, put up against Windham.

His testimony concerning what exactly he thought Windham was suffering from was a confused and incoherent finding of so-called ‘amentia (“not downright idiocy, but something between idiocy and lunacy.”).

The psychiatric case against Windham was strongly based upon the assertions that he was an imbecile and that his marriage to an ‘immoral woman’ like Agnes Willoughby was compelling evidence of something called ‘moral insanity’.

See Inconvenient People by Sarah Wise.

Dr Thomas Harrington Tuke

Dr Harrington Tuke was the leading defence medical witness. The defence experts in general characterised Windham as boysterous and immature, but disbelieved in the concepts of ‘amentia’ (“an exploded term”) and ‘moral insanity’.

They argued that no degree of simple eccentricity (such as a young nobleman choosing to act as a sweep and carry a soot-bag in the street) would amount to madness. This reflected a pronounced current of public opinion to the effect that Windham’s actions, however questionable, were his own business and that he should be free to marry whomsoever he wished.

Dr Harrington Tuke was the leading defence medical witness. The defence experts in general characterised Windham as boysterous and immature, but disbelieved in the concepts of ‘amentia’ (“an exploded term”) and ‘moral insanity’.

They argued that no degree of simple eccentricity (such as a young nobleman choosing to act as a sweep and carry a soot-bag in the street) would amount to madness. This reflected a pronounced current of public opinion to the effect that Windham’s actions, however questionable, were his own business and that he should be free to marry whomsoever he wished. Sir George Armytage

It fell to a ‘special jury’ of twenty-three men of high social standing to decide the issue, of whom sporting Yorkshire baronet Sir George Armytage was elected Foreman.

It fell to a ‘special jury’ of twenty-three men of high social standing to decide the issue, of whom sporting Yorkshire baronet Sir George Armytage was elected Foreman.

The frequently repetitive hearing became something of an endurance test for these gentlemen, straddling the Christmas of 1861 and lasting from 16th December to 28th January in cold and uncomfortable courtroom conditions.

If their verdict went against Windham, then his freedom of action would be ended. The victors could then apply to the Court of Chancery for committees to be formed to supervise both his person and his property.