Travel by bus, or “omnibus”, could be a hair-raising business in the first half of the Nineteenth Century. Collisions occurred, axles broke, wheels came off, and horses fainted or bolted. In the absence of fixed stops one had to step out into the unregulated traffic and hail the contraption down, then climb a precarious ladder to perch outside on top if the cramped interior was full. Dangerous overcrowding was commonplace. All human life was consumed by the omnivorous omnibus, as I shall illustrate here with reference to Leeds and London. I shall also suggest how the humble omnibus presumed to change the fate of nations.

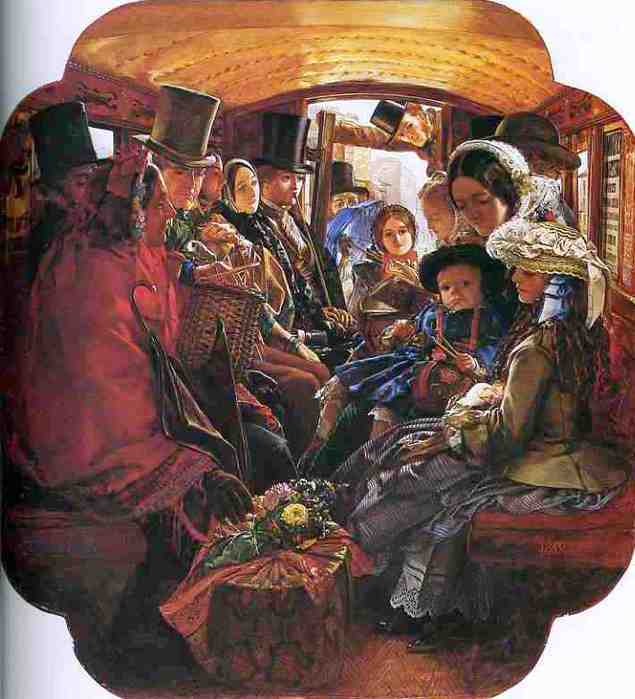

“Omnibus Life in London” by William Maw Egley, 1859. A vivid glimpse into a lost world.

In Leeds the first suburban omnibus began running out to Headingley, then a fair way out of the town proper, in June 1838. For a sixpenny fare, and laid-on “for the accommodation of merchants and others”, it was at first rather an exclusive service. Indeed only one vehicle worked the route initially, doing round trips between the Three Horse Shoes in Far Headingley and the Wheat Sheaf Inn on Upperhead-Row, via The Oak. And early omnibuses were small, seating only ten or twelve persons facing each other in two rows inside, and, later, the same numbers again seated back-to-back on a rooftop “knife-board”. (The Leeds Mercury 30/06/38; The Leeds Intelligencer 30/06/38, 2/7/42).

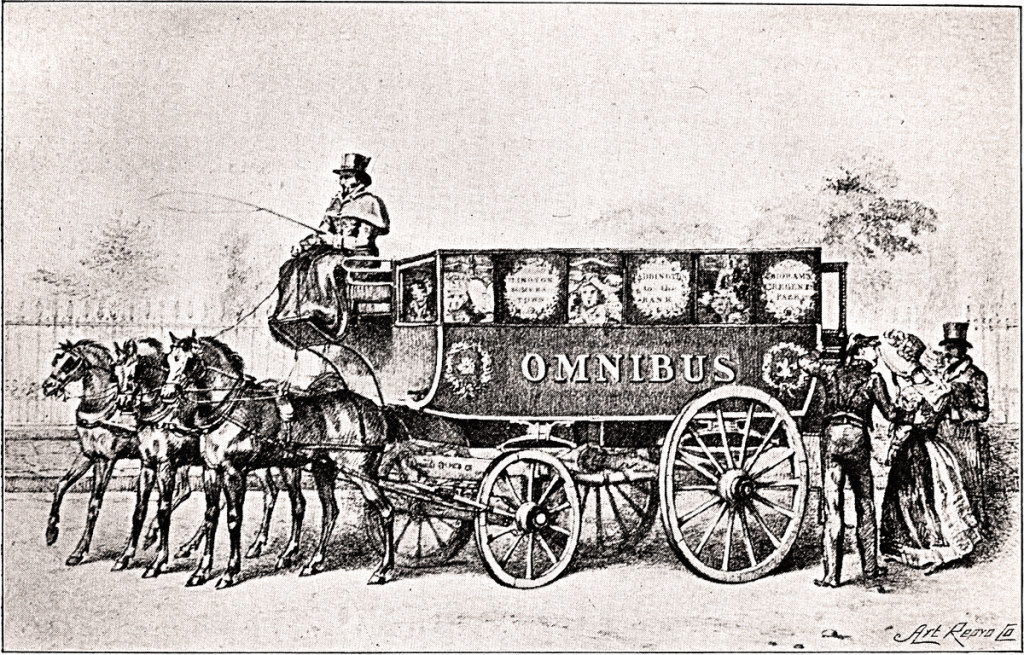

“Omnibus” by David W. Bartlett.

More suburban routes swiftly followed, their vehicles bearing grand names like “The Wellington” and “The Royal Sovereign”, though comparative social exclusivity did not necessarily guarantee good behaviour. In 1839, a lawyer returning to Leeds too late to get home to Bradford took the Kirkstall omnibus instead, with a view to staying at the Star and Garter Hotel there. According to a witness at a subsequent court action he had been drinking at the Griffin Inn, the Boar Lane town terminus, when he got on board and “appeared to be in liquor”. He was alleged to have broken a pane of glass during the journey, which he subsequently refused to pay for, and he was taken into custody. One can imagine the headline appearing today: “Boozy Bradford Barrister Breaks Bus Window”. (The Leeds Intelligencer 12/9/1840, 5/6/41; The Leeds Mercury 26/11/42).

Bad behaviour was not confined to passengers. In 1843, a driver of the Kirkstall omnibus was fined 5 shillings, with costs, by the magistrates, for leaving his vehicle unattended for some time in front of the Griffin’s taproom. In 1844 another driver, named Joseph Coghill, was fined 20 shillings, with costs, for leaving his vehicle and horses unattended for a lengthy period, whilst he was “moistening his clay” in the same taproom. The recidivist Coghill, now driving the Leeds and Bradford omnibus, was again fined for the same offence in 1845. Also in that year he was charged with “wanton cruelty” to one of his horses and was separately convicted of “furious driving” in a manner “dangerous to the public”. (The Leeds Intelligencer 9/9/1843, 8/6/44; The Leeds Times 4/1/45, 1st February 1845, 26/3/45).

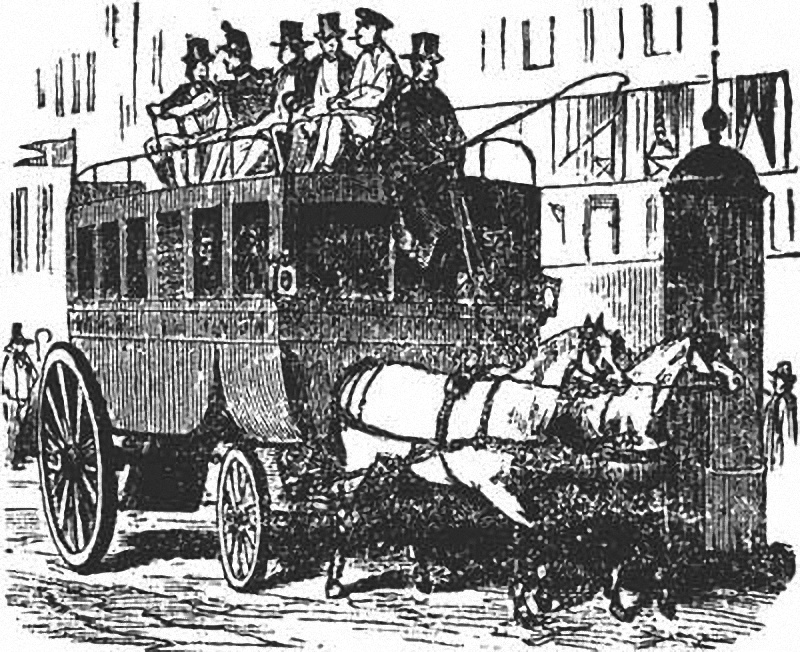

Illustrated London News, 1840.

Instances of “furious driving” were common, especially in London where multiple routes quickly proliferated and there was keen competition for passengers. The first London service was established in 1829 by a (British born) former Parisian resident and coach-builder named George Shillibeer. It ran from the Yorkshire Stingo pub at Paddington along the New Road (Marylebone Road and its continuations) to the Bank of England. The conductors he employed were notorious for pilfering from their employer, so that while passenger numbers went up, cash receipts came down! (Omnibuses and Cabs: Their Origin and History, H.C. Moore, London, 1902).

Shillibeer’s First Omnibus, 1829.

London conductors were known as “cads”, while the drivers were dubbed “jarveys” (or “jarvies”), and both acquired a reputation for dishonesty and bad behaviour. Under the headline “Tricks of Omnibus Conductors”, a case came before the Mansion House magistrates’ court in the City whereby a conductor was fined for misrepresenting his vehicle’s destination to a passenger, when he had no intention of going that far. “The public might form some idea of the extent to which impositions of all kinds are carried on by omnibus conductors and drivers when they are informed that Mr Goodman” [the court clerk] “stated that upwards of 4,000 summonses had been issued against them within the last year”. (The Northern Star 30/6/1849).

A summons was issued against a Mr Waddelove, conductor of the Hoxton to Chelsea omnibus in 1848, for offensive conduct towards some female passengers, “who complained that he had grossly insulted them, and assailed them in the most indelicate manner as they were stepping out of the omnibus.” When “gentlemen present remonstrated with him upon such disgraceful conduct…the defendant, who was evidently intoxicated, commenced swearing at them and assailing them with abusive epithets…”. He subsequently assaulted one of the gentleman, and he was deprived of his licence and ordered to pay a 40 shilling fine or serve two months imprisonment. (The Northern Star 7/10/1848).

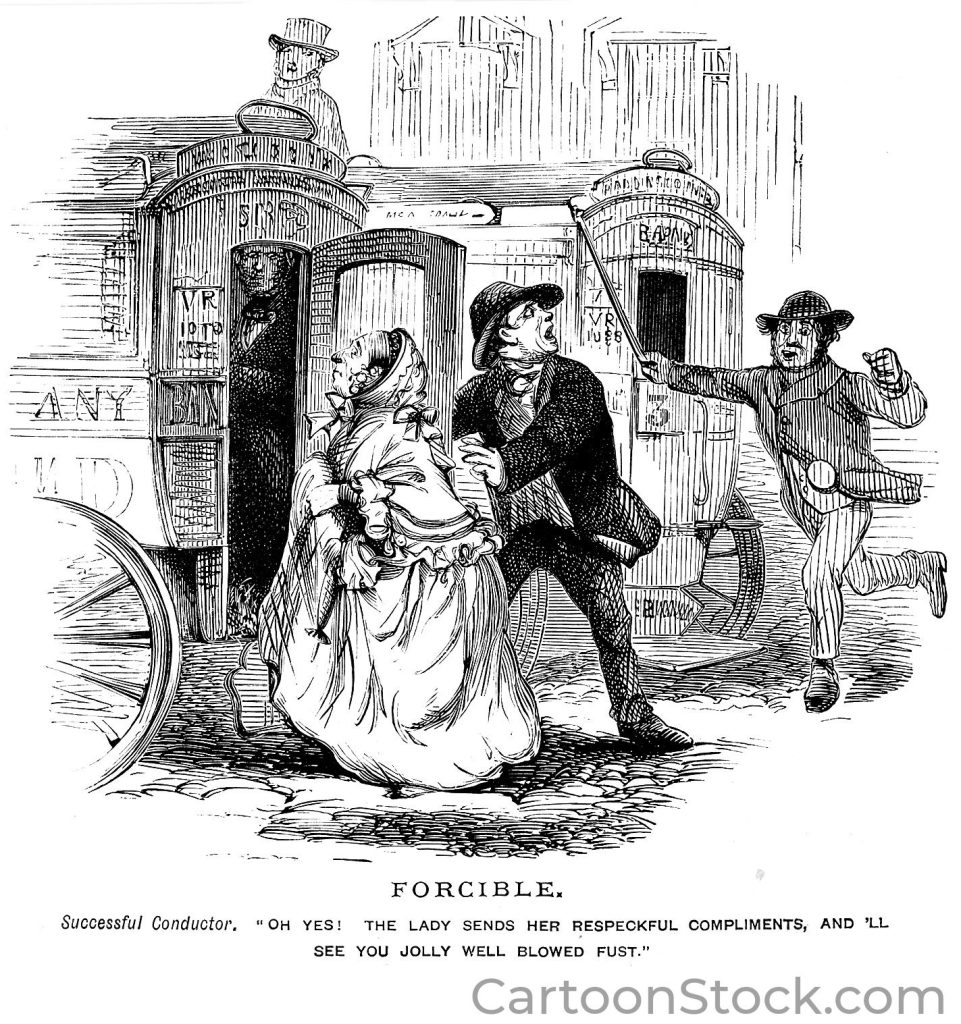

“Forcible”. Punch, by Cuthbert Bede. Cartoon illustrating competition between omnibuses for passengers.

In “a suitable warning to his brother jarvies” in 1840, a London omnibus driver received one month’s imprisonment, with hard labour, for reckless driving. Another jarvey, named William Gilbert, had a verdict of manslaughter given against him at an inquest in 1844, arising “out of the usual offence of omnibus racing”. Evidence was given that Gilbert’s omnibus, owned by Peter Mountain, had got into a race with another, owned by the Conveyance Company, near King’s Cross, as a result of which the wheel of a gig was clipped, causing the elderly farmer driving it to be thrown down to his death. At trial, Gilbert was acquitted of manslaughter, but only due to doubts over the deceased’s sobriety at the time of the accident, and concerning the proper allocation of fault. (The Leeds Mercury 20/6/1840; Northern Star 27/1/44; Lloyds Weekly London Newspaper 28/1/44; The Weekly Chronicle 17/2/44).

Accidents, often leading to fatalities, were regular occurrences. One might be run over, or pitched from the roof into the street, as happened to Mr Flooh, the resident clown at Batty’s Hippodrome, Kensington, in October 1851. He had caught the omnibus home after one of his performances when it collided with a “ruck in the road” on Oxford Street. He was removed to hospital whereupon, “it is probable that Mr Flooh will be unable to follow his vocation for some time.” Some passengers simply died natural deaths, whilst yet seated aboard, an end that overtook the principal clerk of Coutts & Co., on the Bayswater omnibus in April 1847. In January 1853, a cigar box containing the dead body of a new-born infant was found left on a London omnibus seat. (The Northern Star 17/4/1847, 11/10/51; The Leeds Times 15/1/53).

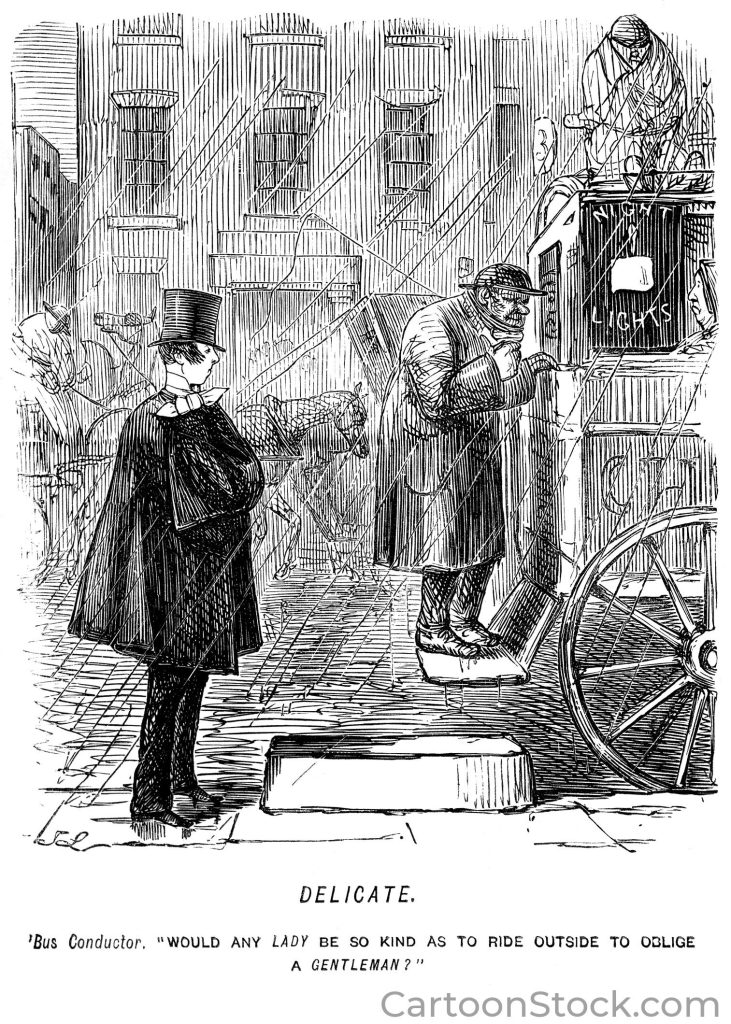

“Delicate”. Punch, by John Leech. Gentlemen were supposed to allow ladies seats inside, whilst they rode on top.

The “Atlas” omnibus, plying between Elephant and Castle and Paddington, was standing by the Obelisk on London Road in January 1844, receiving luggage on its roof, when its pair took fright and bolted. The jarvey was thrown from his box, sustaining severe head injuries, and the “fine-spirited animals…galloped furiously up the Westminster-road”, then, “dashed violently across the foot pavement into the shop-front of Messrs. White and Co., tailors and drapers, Hercules-house, Mount-street. The shop-frontage consists of immense panes of plate glass, two of which were completely shattered. The only passenger the omnibus contained was a lady, who had fainted during the time the vehicle was in its impetuous course…but without receiving further injury.” What happened to the horses is unclear. (Age And Argus 27/1/1844).

A “Ludicrous Accident” befell the occupants of a Chelsea and Fulham omnibus near Charing Cross in October 1840. “The vehicle had a full complement of passengers – two rows of ladies and gentlemen seated with due decorum on either side, and looking at each other with becoming gravity – when, just as the omnibus entered the Strand, one of the wheels came suddenly off, and the ladies and gentlemen seated on the off side were precipitated into the laps of the ladies and gentlemen on the near side, to the utter discomfiture of all parties…Fortunately, however, no serious injury occurred, the utmost mischief that resulted being the damage of one gentleman’s inexpressibles, by the breaking of a basket of new laid eggs which the lady who honoured him with her embrace was conveying as a present to a friend in the city.” (The Leeds Times 17/10/1840).

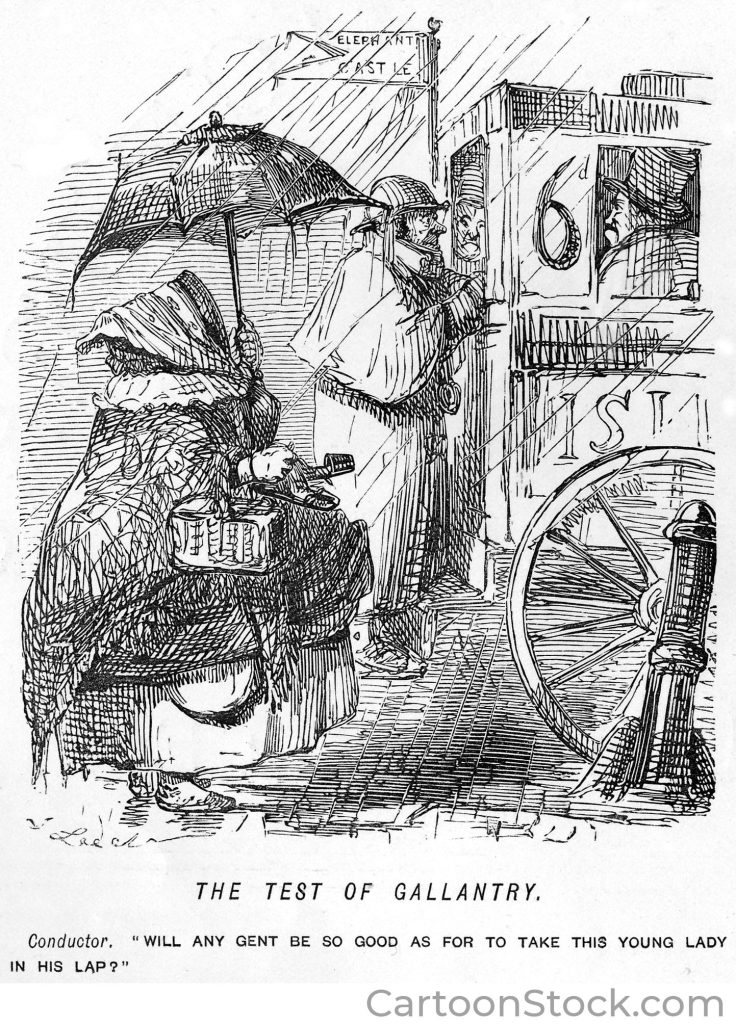

“The Test of Gallantry”. Punch, by John Leech.

It seems that gentlemen sometimes did allow ladies onto their laps – only to rescue them from inclement weather of course! One very wet evening in June 1851, an Islington omnibus drew up at the Angel Inn: “A well-dressed female, who had charge of a trunk and several band-boxes” was told that the omnibus was full. “A rich stock-broker, who was inside, either compassionating the young woman’s condition, or noticing that she was pretty…” offered to accommodate her on his knee. “The gentleman placed his arm around the young woman’s waist and held a conversation with her in an undertone, till the omnibus stopped at Tollington Park.” Both alighted here whereupon the young woman, with all her luggage deposited on the pavement, asked him where a certain gentleman of the neighbourhood might live, to which he replied that he was that very same gentleman. She then said that she had been engaged by his wife as a cook, to take up residence today. “The young woman had actually ridden home on the omnibus on her master’s knee,” the report concluded, adding, “How the matter ended has not transpired.” (The Leeds Times 7/6/1851).

“L’Omnibus: A Busy Town Square, Paris, 1908”. Eugenio Alvarez Dumont.

Romance might blossom in a crowded omnibus on a wet day, but passengers might just as well be robbed by their fellow travellers. In July 1843, R.H. Blakemore, M.P for Wells, was deprived of three £1,000 notes in an omnibus while proceeding from his bank in Ludgate Hill to his home in Regent Street. One banknote soon reappeared at the Bank of England in Liverpool, presented by “the keeper of a disreputable house” in that town. The other two notes did not surface until 1848, when they were presented for encashment by a south-London publican, who claimed he had won them in a wager with an (unnamed) “respectable” gentleman at Epsom races. (Berrow’s Worcester Journal 27/7/1843; The Leeds Intelligencer 10/6/48).

In September 1844, a messenger of the Great Western Railway Company was despatched to take 800 sovereigns and £500 in bank notes from Paddington station to the company’s banking house in Lombard Street by omnibus. Whilst sitting on top, the blue bag in which he was conveying the money was substituted for a blue bag “exactly resembling it, and filled with old pieces of lead and copper”, and the fact was not discovered until he reached the bank. One senses an “inside job” here. (The Leeds Intelligencer 14/9/1844; The Leeds Mercury 14/9/44).

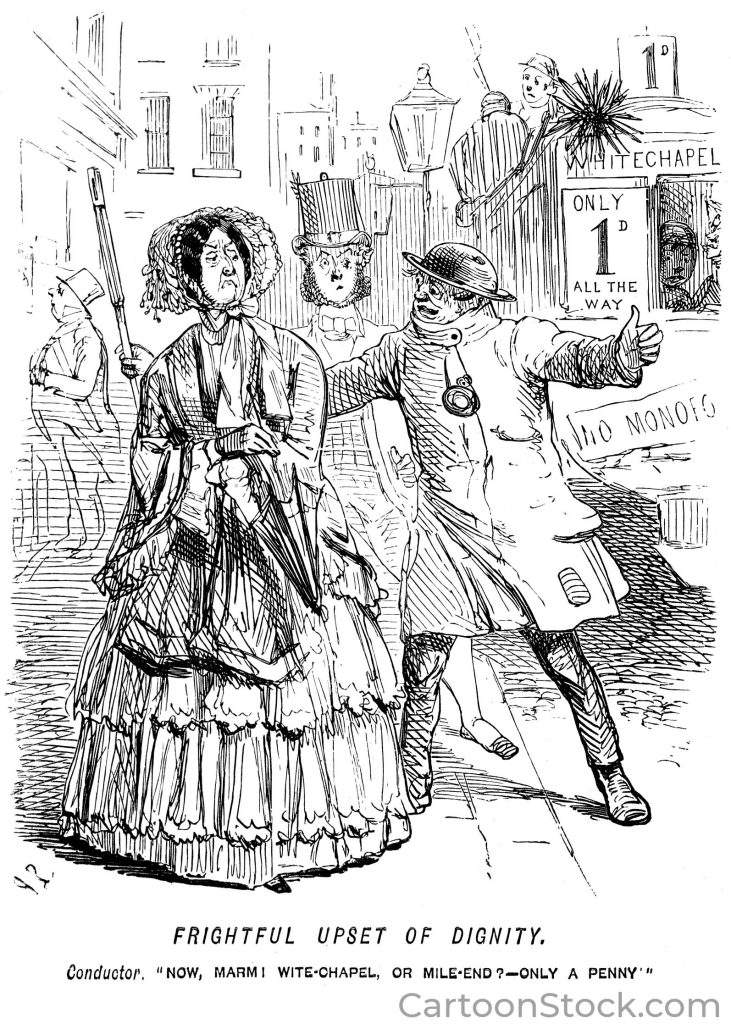

“Frightful Upset of Dignity”. Punch, by John Leech.

And honesty was not always rewarded. In May 1846, a young man riding in an omnibus from Regent’s Park to the Bank “found in it an elegant silver card-case”, containing £140 in bank notes and the address of the owner. “He immediately delivered the card-case and contents to the owner, a lady, and received an answer that ‘she would think of him,’ but up to this time her recollection seems not to have suggested the propriety of rewarding a person to whom she is so much indebted, as he has not seen or heard anything of her.” (The Leeds Times 9/5/1846).

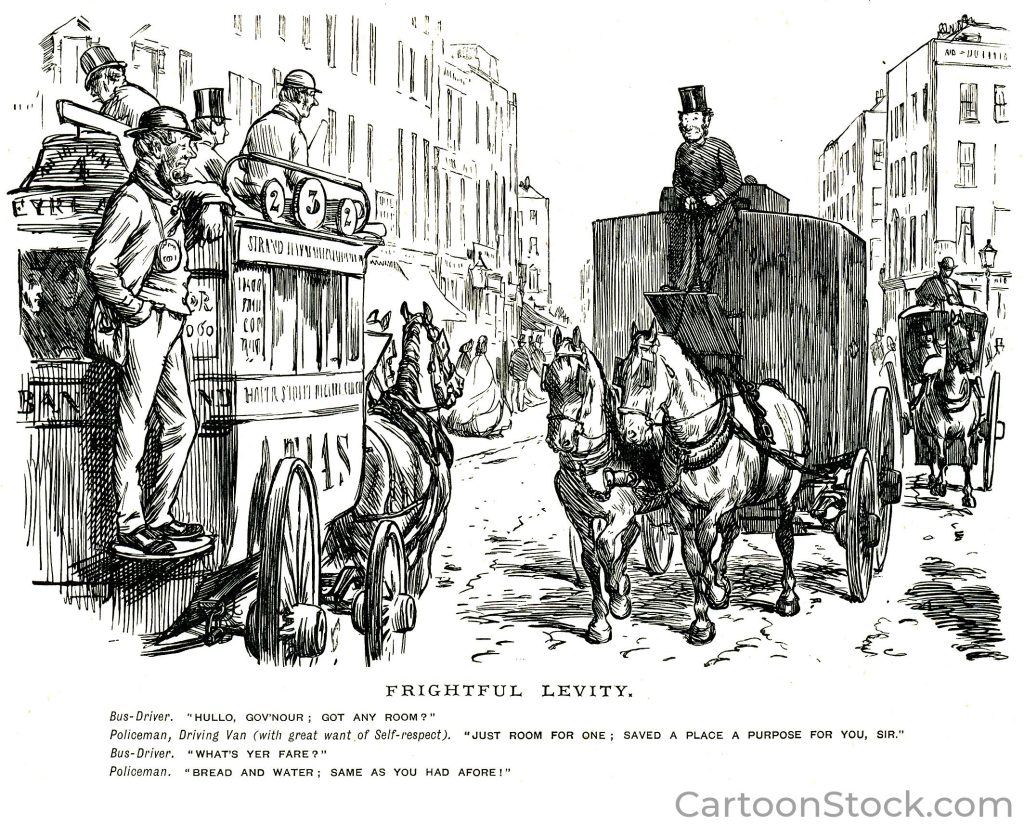

An innocent gentleman, “who had every appearance of being one of the higher class of society”, appeared to almost demand being treated as a criminal in a “Ludicrous Affair” on a rainy day in December 1840. He hailed down a police van, thinking it was the Belgrave Square omnibus, explaining his mistake by stating that the Macintoshes worn in the wet by those he took to be the driver and conductor had obscured their police uniforms. (The Northern Star 12/12/1840).

“Frightful Levity”. Punch, by Charles Keene. So easy to mistake a police van for an omnibus!

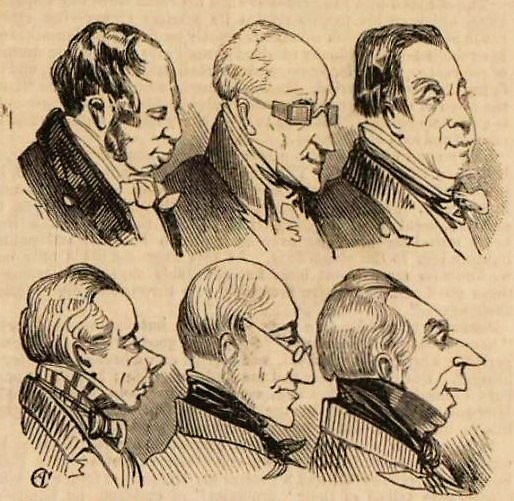

One might encounter far-flung characters when travelling by omnibus. In March 1843, a party of “Ojibbeway Indians” from North America boarded an omnibus to visit the first tunnel bored under the Thames, running from Wapping to Rotherhithe. On their alighting, “The appearance of feathered heads, painted faces, bear-skin garments, and mocasined legs, in the classic locality of ‘Wapping Old Stairs,’ created a general hubbub…The ladies were very active in shaking hands with the redskins.” (The Northern Star 23/03/1844).

“Heads from an Omnibus”. Illustrated London News, 1843. No sign of headdresses or painted faces here.

Serious disorder might sometimes occur. In October 1848, a gentleman and his wife boarded a midnight Chelsea omnibus outside Cremorne pleasure gardens, and the following ensued: “A great number of persons got on the roof, and two others hung on to the steps behind. While the omnibus was making its way down Sloane-street, the persons outside, who were evidently the worse for liquor, began singing and making a great noise. The omnibus stopped before a public house, and some of the passengers got down and had refreshments…The omnibus, after waiting some time, went on, and the noise outside was continued. Some of the persons outside let off fireworks. One person, whose legs hung over the side of the omnibus…placed a catherine-wheel at the end of a stick and set fire to it…The sparks from the fire-work came into the omnibus over the passengers, and caused much alarm.” When the gentleman spoke to the conductor about the situation, he merely said, “Oh, It’s all right”. (The Northern Star 7/10/1848).

There was widespread disorder across Europe in that year of 1848. This was sparked by the February revolution in Paris, which cased the abdication of “Citizen king” Louis Phillippe and his replacement by the French Second Republic. Under the headline “Omnibuses And Coaches During A Revolution”, it was reported that, “In the Rue St. Honore…several attempts to raise barricades were made. The pavement was torn up in several places; omnibuses seized and upset – one in such haste that the passengers had not time to get out, but all were tumbled over along with the vehicle…in the Rue Richelieu, a gun shop, strongly fortified with iron shutters, was…broken into by means of an omnibus, which was used as a battering ram…” (The Leeds Times 4/3/1848).

“Barricade on the Rue Soufflot”, 1848, Horace Vernet.

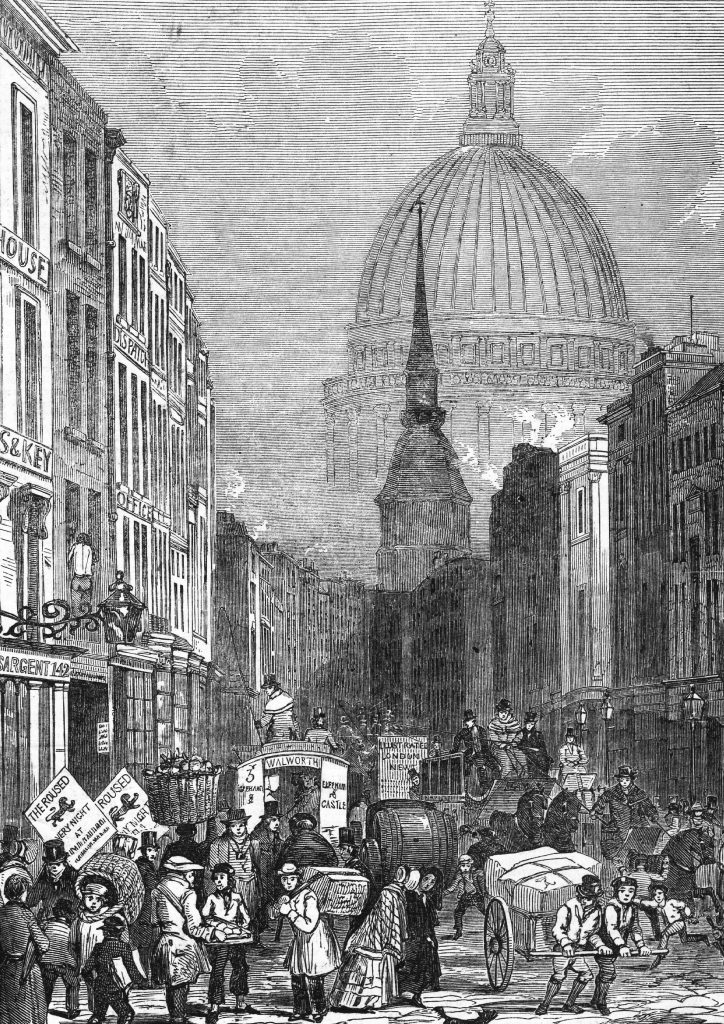

So it could be claimed, in 1849, that, “Few things in modern times have been such influential agencies as the omnibus…Those social conveniences have revolutionised all the chief capitals of Europe…The accidental upset of an omnibus suggested the first idea of a barricade…The overturn of a carriage was converted to the overturn of a monarchy.” But, at the same time, “Among ourselves it is a peaceful and health-giving instrument. By its help all the world is able to live out of town. Barristers, merchants, artists and men of letters, who formerly crowded the narrow passages of Fleet Street and Cheapside, live now, by its permission, in snug suburban cottages in Norwood, Hampstead, Putney or Blackheath.” (The Northern Star 3/11/1849 – reproduced from The Athenaeum literary magazine).

I am indebted to the British Newspaper Archive for access to the above articles, as identified by publication and date:

Another magnificent article from this self-effacing Literary Nobody.

There is a cornucopia (certainly not a plethora) of stories of incidents and adventures ranging from omnibus races that would rival Ben Hur to Parisian ram raiding via an elegantly-phrased mention of a gentleman’s unmentionables. All of human life is here, on the mid-nineteenth century omnibus.

Well-written and carefully researched as always. Would that these blog posts arrived more often.