Sadly, no trace remains of Liverpool Zoological Gardens, “a place of favourite and fashionable resort” in its day, which graced the south-side of West Derby Road beyond the old Necropolis from 1833 to 1865. Indeed, there are few relics nowadays of the Victorian terraced housing which subsequently dominated the area. The Gardens enjoyed an eventful history that I shall describe below, which involved a glorious rise and an ignominious fall.

The Zoological Gardens were opened on 27th May 1833 by Thomas Atkins, the long-time proprietor of a travelling menagerie, the beasts of which were, of course, destined to form its principal attraction. Now nearing his seventies and no-doubt tired of life on the road, Atkins had acquired an old brick-field and pit named “Plumpton’s Hollow” on the edge of town for his purpose. This had been notorious as “a place where multitudes of the lower orders have hitherto been accustomed to resort for the enjoyment of prize fights, and similar amusements”. Atkins had determined to transform it into a pleasant attraction for respectable townsfolk where, “every attention will be paid to the preservation of order and the exclusion of improper visitors…”. (The Liverpool Mercury 22/2/1833, 31/5/1833).

Liverpool Zoological Gardens. Liverpool Zoo/Zoological Parks

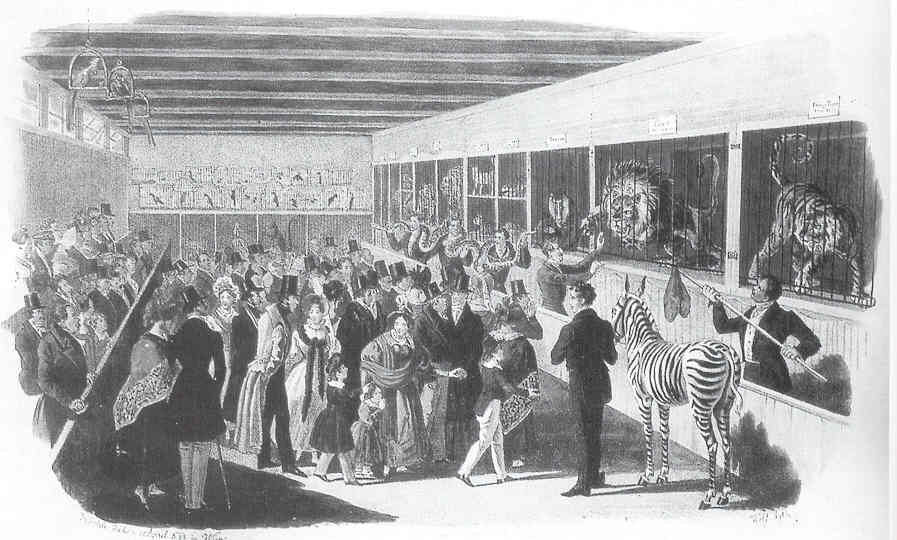

The existing excavations made the chosen plot ideal for landscaping into a scenic garden, arranged around a natural amphitheatre. A circular grand-menagerie was built in this depression, next to a lake, and there was a monkey house, an elephant house, a bear pit, an eaglery, an aviary, and a waterfowl pond, all suitably populated. There was also a concert room, a refreshment room, and an orchestra-stand on a lawn. Shortly after its opening, the “inducements to a visit” were described as, “extensive grounds very beautifully laid out, a very numerous collection of animals and birds so disposed as to be seen to the best advantage, and the charms of music…giving life and animation to the whole.” Later, there was also a centrifugal railway and a camera obscura. One Monday in June 1833, there were estimated to have been between three and four thousand visitors, entrance being restricted to annual subscribers and their families, and only such others as could pay a shilling and produce a pre-booked Visitor’s ticket. (The Liverpool Mercury 22/2/1833, 31/5/1833, 21/6/1833, 28/6/1833, 25/12/1835; The Liverpool Standard 1/10/1833; The Liverpool Mail 7/8/1847).

Zoological Gardens, Regents Park, by George Scharf, (Aviary) (1835). Public Domain

Zoological Gardens, Regents Park, by George Scharf, (Monkey House) (1835) . Public Domain

Of course ships put into Liverpool from all over the world, and they soon began to bring exotic animals with them to augment the Gardens’ menagerie. Many citizens also seemed to have curious specimens available to contribute. The Liverpool Standard of 7th April 1835 cited the following presents (amongst numerous others) as having lately been received by the gardens: “An Ursine sloth and a monkey from Captain Harding, ship Bounty Hall; an American black bear from Captain Nicholson, ship Tally Ho; a Caffrarian cat from Captain Adam McMinu, ship Hibernia; an Indian buffalo from Captain Ellis, ship Tyrer…etc…”. On 28th July 1836, Gore’s General Advertiser catalogued, amongst many live donations recently made: “…a king vulture, from Robert Gladstone, Esq, Abercromby-Square…a whistling duck, Captain Bispham of the Sandbach; a red curassow, a crocodile, and three tortoises, Captain Burnett of the Montezuma; a pair of Muscovy ducks and three snapping turtle, Captain Curtis of the Kensington…”. In September 1836, Captain Kellock of the East India ship the Cestrian presented the gardens with a tiger that had belonged to the Nizam of Hydrabad, and which had reputedly devoured sixteen sheep on the voyage over from Bombay. (The Liverpool Standard 6/2/1835, 7/4/1835, 7/7/1835, 16/9/1836; Gore’s General Advertiser 28/7/1836; The Liverpool Mail 15/12/1836).

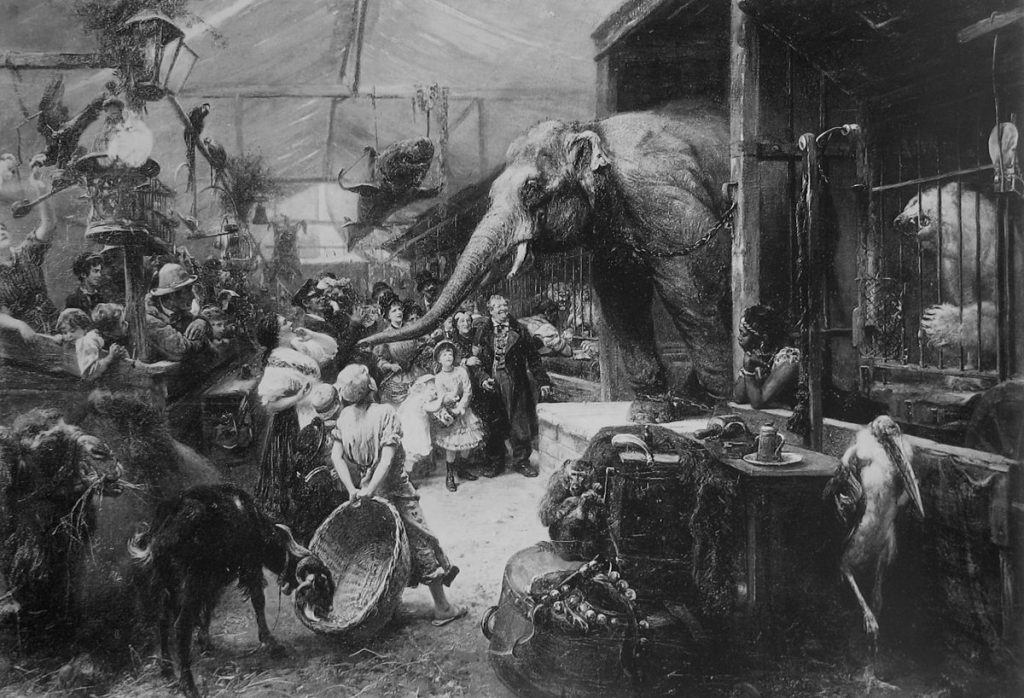

Menagerie, by Hermann Van Aken, (1833). Public Domain

Strangely, two (unnamed) men were brought before the city magistrates in late 1833 charged by Mr Atkins “with having represented themselves as belonging to the Gardens, and having obtained in that character from captains of vessels, different animals intended for that establishment.” However, “After hearing the case, the magistrates decided that there was not sufficient evidence to convict them of fraud, but cautioned then not to appear there again, lest they should stand in a very different situation.” (The Liverpool Mercury 4/10/1833)

Atkins was certainly not short of animals to exhibit, so that one wonders how such a diverse bestiary might be properly fed and looked-after. And he was always on the look-out for new additions. In June 1835, “Mr Atkins, the indefatigable collector of curiosities, is gone on a special mission to London, for the purpose of inviting some illustrious strangers, now in town, to partake of the illustrious hospitality of his gardens. He is expected to return, in the course of the week, accompanied by a male and female nylghou [large Indian antelopes], and their young family, a cassowary [a flightless New Guinean bird], some black swans, and several other birds and beasts.” (The Liverpool Standard 9/6/1835).

Isaac Van Amburgh with his Animals by Edwin Landseer (1839). Public Domain

And the animals were far from being the Gardens’ sole attraction. For instance, in August 1834, Atkins was advertising evenings wherein, “The Grounds and Principal buildings will be Splendidly Illuminated with Coloured Lamps arranged in Arcades, Festoons, Stars, Flowers, &c, &c…” There was to be the spectacle of a balloon ascent and the accompaniment of a military band, and the evenings were to culminate in a firework display. The Gardens manufactured its own fireworks, and ambitious pyrotechnic performances featured regularly throughout its existence, though it is not recorded how its more timid residents tolerated these explosive disturbances. (The Liverpool Mercury 1/8/1834)

The Gardens opened in spring for each year’s season, with a program of events to last through to the autumn. Each season’s centrepiece was usually a topical tableaux, based upon recent dramatic happenings such as a battle, a siege, or an outbreak of revolutionary violence. In 1838, in view of its eruption in recent years, “The whole of the east side of the garden was laid out to represent Mount Vesuvius, towering above its adjacent hills, and, at its feet, Naples and its beautiful Bay…the optical illusion was accomplished by means of small hillocks and painted canvas…The lighting eruption began at 9 o’clock…At first, a thin column of smoke issued from the crater and rose in the air…After an interval a brilliant flash succeeded…Presently the flashes became more frequent, and flame mingled with the smoke at the craters mouth ever and anon changing its tint from a violet to a livid and from a livid to a crimson hue…Vesuvius opens, as it were, her womb, and pours forth an overwhelming flood of molten fire, carrying desolation in its path…” (The Liverpool Standard 8/6/1838)

There were some real-life, rather then merely figurative, mishaps along the way. William Mayman, a West Derby Road publican, stated that, early one Sunday evening in October 1838, “I was standing at my own door, near which was a man with a basket of nuts for sale. This man first saw a large bear make his way over the gate into the lane. He immediately threw his basket to the beast, and it began to eat the nuts. At this moment a child, being on its way to buy some nuts, I ran and caught hold of it to bring it to my house for safety. Before I had advanced many yards, the bear jumped upon my back, sized me by the right arm, and began to grind it with his teeth in a dreadful manner.” After a prolonged struggle, “the keepers of the gardens came and beat him off, just in time to save my life.” Unfortunately Mayman had been severely mauled in saving the child, and was henceforth subject to such bad fits that he took his own life by arsenic in 1845 (aged only 36). Bizarrely, Mayman’s pub was actually called “The Bear”, a name his widow later declared it had borne even before the attack! (The Liverpool Standard 19/10/1838, 11/2/1845; Gore’s General Advertiser 27/5/1841; The Liverpool Mail 8/2/1845; The Liverpool Mercury 3/11/1864).

Animal Shack, Paul Tierbude, Photo engraving after a painting by Paul Friedrich Meyerheim (1885). Public Domain

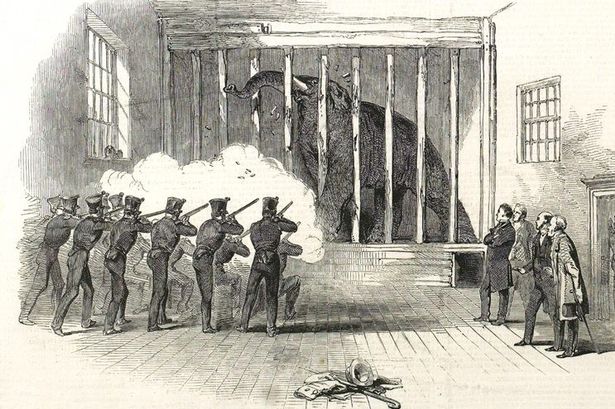

Thomas Atkins died on the 6th June 1848, aged 84, described in his obituary as, “most liberal to all connected to the large establishment of which he was the head.” The saddest incident in the Gardens’ history coincidentally followed less than two weeks later, when his beloved elephant Rajah, whom he had owned for over eleven years, followed its master to its demise. The poor beast grew infuriated after being struck twice with a broom by its keeper (Richard Howard), to make him budge, and he ran at the man, jammed him against the bars of the cage, let him fall, and then crushed him to death underfoot. Rajah had killed a keeper (Henry Andrews) in this manner before, one night in 1843, when “The handle of a broom, with which the deceased had often struck the animal, was found near the place, broken in two pieces.” Rajah was not forgiven this time, and Atkins’ sons John and Edwin first resolved to poison the creature, then, that having failed, had him shot by a company of riflemen. The keeper’s widow, Sarah, died “through excessive grief” soon afterwards. (The Liverpool Mail 23/12/1843, 11/11/1848; The Liverpool Standard 13/6/1848, 20/6/1848).

The Shooting of Rajah. Public Domain

The Gardens were, perhaps, never the same again. Shifting priorities were suggested by the new proprietress, Atkins’ widow Elizabeth’s, subsequent efforts to secure a wine & spirits licence for the premises (it already had a beer licence). A lawyer named Mr Snowball opposed her 1851 application, ostensibly on the ground that, “It would be very dangerous to allow parties to partake of spirits in a zoological garden, for many accidents, it was well known, had happened from persons poking the dens of wild beasts even when sober…” (Such examples of “Temerity Punished” had indeed arisen before, one man having had his hand “severely lacerated” in 1847 by a lion he had been “teasing” with a stick.) The real reason for the magistrates’ rejection of Elizabeth’s applications probably lay in their reluctance to see the Gardens descend into disorder and prostitution, such as was notorious at London’s Cremorne pleasure garden. (The Liverpool Standard 17/8/1847; Liverpool Mercury 12/9/1851).

In January 1852 Elizabeth sold the Gardens to Mr John Durandu, “a bullion dealer and exchange broker, Waterloo-road”, whose brief period of ownership does not seem to have been a happy one. In December of that year he brought a complaint against a police officer, who had insisted on taking him up as “drunk and disorderly”, despite his affirmation that he was “perfectly sober at the time”. The Liverpool Mercury speculated that 1852 “cannot have been a profitable season.” He had his own license applications rejected, and in March 1854 sought to recover £10 from Elizabeth Atkins in the County Court in respect of “four macaws and a parrot” he alleged had gone missing. (The Liverpool Mercury 24/2/1852, 10/9/1852, 21/3/1854; The Liverpool Mail, 25/12/1852).

By April 1854, Atkins’ son John had taken the Gardens back into family ownership. And, “In order to secure some new and curious specimens of the animal world,” his brother Edwin had “started, in 1852, on the perilous journey of exploring the almost unknown tracts of the interior of Africa. He had been most successful in his daring adventure, having secured several specimens, when death overtook him on a small island on the White River, a branch of the Nile, in January last.” This was quite notable, considering that David Livingstone’s famous Nile explorations did not begin for over a decade. But despite Edwin’s enterprise, by 1855 it could be complained that, “It is well known that these gardens do not posses that enormous zoological collection which so distinguished them in former years…” (The Liverpool Mercury 14/4/1854, 21/4/1854; The Liverpool Standard 24/4/1855).

Menagerie. In the Animal Shack by Paul Friedrich Meyerheim (1894). Public Domain

The changing nature of the Gardens is evident from increasing references to “a great number of improper characters” attending them. This euphemism meant prostitutes, “a class whose presence must always prevent families from attending”, and John Atkins’ newspaper advertisements now stated that all such persons would be prohibited admission. Atkins responded to a complaint from “The Society for the Suppression of Vicious Practices”, that “with the assistance of the police, women of the town had in fact been prevented from entering the gardens.” He was finally granted a wine and spirits licence in 1857, which accelerated the Gardens’ slide into vice. A “Temperance Festival” held there in 1858, “was strangely belied by a visit to the alcoholic refreshment rooms, particularly as the evening advanced, the consumption of liquors being in proportion to the extra number of visitors.” (The Liverpool Mercury 29/6/1857, 13/7/1858, 31/8/1858; Gore’s General Advertiser 16/7/1857; The Daily Post 16/7/1857).

Atkins sold the Gardens to the Zoological Gardens Company Ltd (“a company of capitalists”) in early 1860. Despite their promises to increase the stock of animals, when they opened for the season in May 1861, “The most important improvement we have to notice is the new decorations of the immense dancing platform…These have been carried out in a most expensive and expansive style…Completely encircling the platform is an arcade of thirty-two arches… The inner faces of these arches are filled with gas jets…In the illumination of the platform and precincts three thousand gas jets are used and they are surrounded by thirty thousand lustres.” Clearly, the Zoological Gardens had completed the transformation into a Pleasure Garden that the licensing magistrates had feared. When the elephant house burned down in September 1861 all it contained was the skeleton of Rajah, which was thus “reduced to ashes”. (The Liverpool Mercury 30/3/1860, 4/5/1861; The Liverpool Mail 31/3/1860; The Daily Post 7/5/1861, 28/9/1861).

The Dancing Platform at Cremorne Gardens by Phoebus Levin (1864). Public Domain

By now the area was becoming heavily built-up, and the Gardens were no longer on the edge of town. The finances must always have been precarious, with the expense of purchasing, feeding and keeping the animals, and of mounting grand spectacles, offset by the revenues from only a half-year season, and that at the mercy of the weather. And, since their fall from grace, the Gardens were no longer considered a public amenity by the metropolitan great and good. In 1864 the proprietors did offer to sell the land to the corporation for £28,000 to make for a public park, and it was sad that this means of preserving an open space with mature gardens for posterity was declined. Ultimately the temptation to realise the site’s development value, especially that of the frontage to West Derby Road for shops and pubs, proved too much, and the Gardens finally closed on 30th September 1865. The ground was levelled and laid-out for building purposes, with Boaler Street driven right through its middle, served by several streets leading off. Now most of that is gone in its turn, largely replaced by an anonymous industrial estate. (The Liverpool Mercury 8/9/1864; The Daily Post 2/10/1865).

When closure first loomed in 1864, The Liverpool Mercury commented thus: ‘The unenviable character borne by “the gardens” of late years extinguishes all feeling of regret at the fate with which they are threatened. It was not always so. At one time, and that no distant date, the title of “Zoological Gardens” was not the misnomer it has for some time been. The two or three half-starved specimens of the “king of beasts,” and the mangy monkeys, which a visitor to “the gardens” in recent times might, after much searching, find, were but the miserable remnants of one of the finest collections of animals in the kingdom, representing in value many thousands of pounds. In those better days, too, “the gardens” were the favourite resort, not of the demi-monde but of the “upper ten thousand,” as well as of the numberless lower ten thousand who could only claim to be honest and respectable.’ (The Liverpool Mercury 19/10/1864).

Additional Sources: “The Streets of Liverpool” by James Stonehouse, pp., 116-21 (1869); Entry for Thomas Atkins in the Oxford DNB; “A History of Zoological Gardens in the West” by Eric Baratay & Elisabeth Hardouin-Fugien (2002)

Nice to see this article reproduced in the Liverpool History Society’s Journal 22 for year 2023