One of the most prominent and distinctive buildings on nineteenth century Liverpool’s skyline would have been the beautiful, but now long demolished, St Paul’s church. I have a personal connection to its former site, which I shall explain.

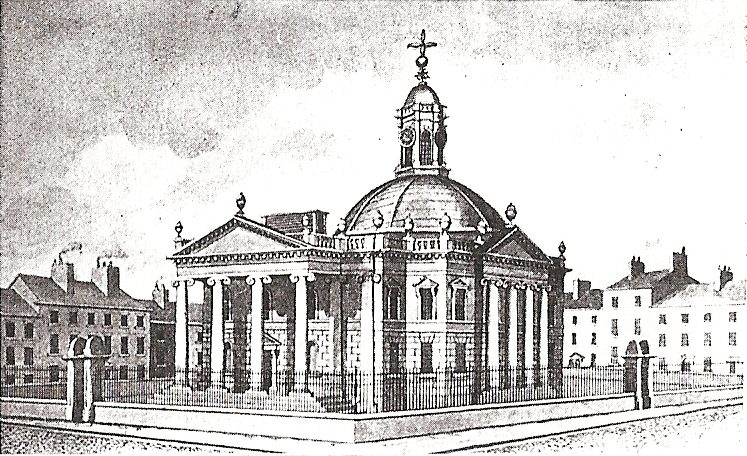

John Raphael Isaac’s bird’s eye view of Liverpool in 1859 depicts St Paul’s standing tall above the neighbouring Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway station (Exchange), and the church’s dome and surmounting ball and cross would have been visible from ships out on the river. It was a smaller version of St Paul’s in London and was built in the mid-eighteenth century on that cathedral’s model, though it was oddly compacted into more of a square (somewhat like a Byzantine cathedral) rather than the cruciform layout of the original. It sat in the middle of St Paul’s Square, which was a prosperous and fashionable area on the fringe of countryside in the mid-eighteenth century, surrounded by stately Georgian terraces. There was the Ladies Walk nearby, where one could stroll beneath a pleasant bower of trees and gaze out over the river.

St. Paul’s from sepia wash drawing by Brierley, 1830

But the prosperous and fashionable soon fled as the explosive growth of industrial Liverpool drastically altered the area’s character. The docks advanced north along its shoreline, bringing warehouses and factories and slums and all the vices of “sailor-town”. The Georgian terraces of St Paul’s Square descended into multi-occupancy, and soon-to-be densely populated courts were erected behind them. The east side of the square was demolished to clear space for building Exchange station, bringing with it noise and smoke. Poor St Paul’s steadily became a church without a congregation as the nineteenth century progressed, many of the incomers being chapel folk or the irreligious. It was closed in 1901 and lay derelict until 1931 when it was, lamentably, torn down.

My own association with the place, although I didn’t know its history then, came sometime in the early nineteen-seventies when I was in my mid-teenage years. Liverpool Boxing Stadium, built on the site of St Paul’s church in the middle of the square, was opened in 1932, and by the seventies it was supplementing its usual pugilistic fare by staging rock concerts. An earlier, long-haired version of myself went to see Arthur Brown’s Kingdom Come there (yes, the “God of Hellfire” himself) and of all the concerts I have seen down the years it remains one of the most memorable to me. Performing on a tiny stage in the middle where the ring usually was, with one half of the hall cordoned off, Brown and his sidemen delivered a highly theatrical prog-rock set. I seem to remember him being in a wooden boat on wooden waves at one point, and at another him climbing into a giant syringe which was then depressed so as to trap him within it. The visuals came from coloured slides being loaded into a projector right next to my seat. Some of these details may well be incorrect (it was 40 years ago), but that’s how I remember it.

These and the more pugilistic entertainments (neither of them to everyone’s taste) were swept away in the mid-eighties when the stadium was demolished in its turn, and the site was left empty for a quarter of a century or so. More recently a great big modern office complex has been built there. Although the structure has a St Paul’s Square address, it overshadows everything around it so it’s hard to picture that this was once a residential square with an attractive church at its centre. Arthur Brown is still going strong though. I have seen him twice since, at roughly twenty year intervals, most recently at the Brudenell Social Club in Leeds when he was on fine form and had an excellent youthful band with him. I hope to see him again in another twenty years. And St Paul’s church, with its surrounding square, lives on in my imagination at least, where it features as a setting in my current fiction writing.