The first underground railway in the world, the Metropolitan, was built in London between 1860 and 1863 from Paddington to Farringdon. Its construction involved the innovation of “cut-and-cover”, whereby roads were dug up, rails and brick tunnels were installed in the cuttings, and the roadway was then restored above. The idea seemed simple enough, but could it be realised in densely populated areas without causing massive destruction to surrounding buildings ? And could the travelling public be persuaded to venture underground, a realm commonly associated with darkness, dampness, sewage and drains? The novelty of the project meant that it’s progress was extensively covered in the press, as I shall explore in this post.

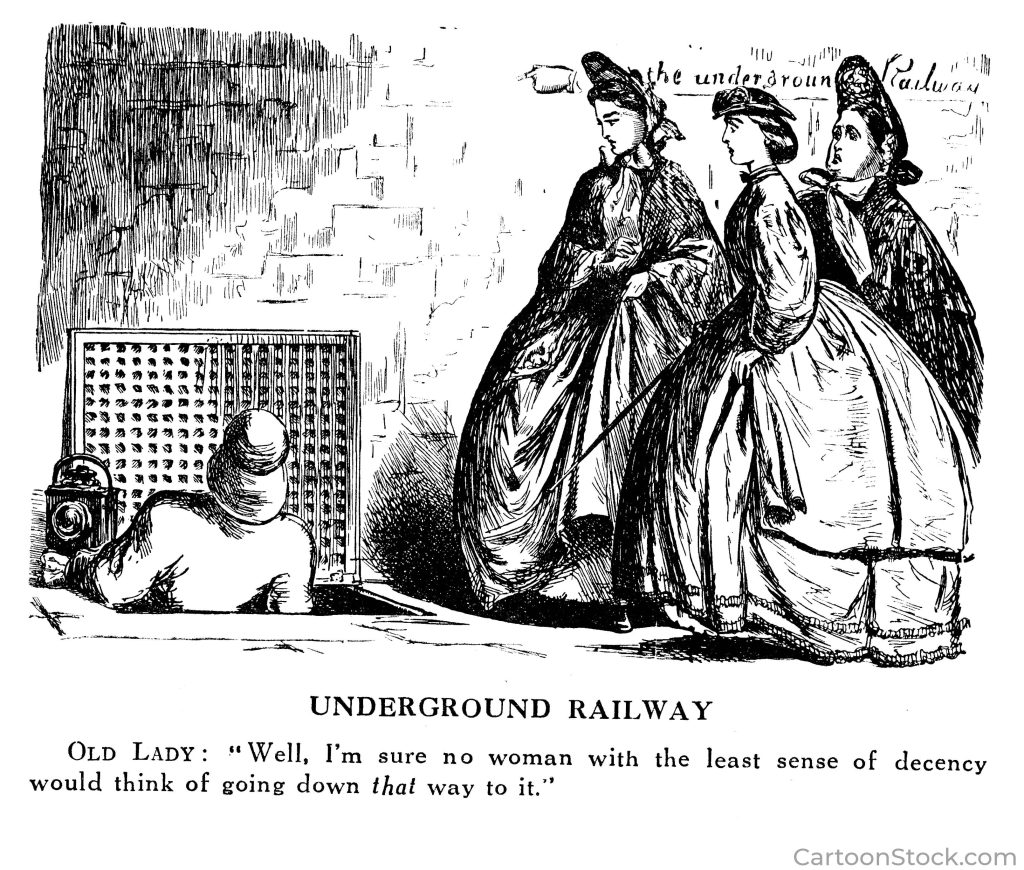

This contemporary Punch cartoon captures the concept’s unfamiliarity.

Such a radical notion could only be contemplated because the gigantic nineteenth century population growth of London had led to chronic traffic congestion on its roads and byways. These were clogged with legions of cabs, carriages, carts, omnibuses, and advertisement hoarding waggons, pulled by slow-moving horses emitting mountains of dung. “Why,” asked The City Press on 18th August 1860, “should London swarm with horses that eat corn beyond all proportion, when science has shown how we may do with a tenth of their number, and be rid of a hundred nuisances and a painfully permanent state of deadlock?”

“The Crowded Streets”, published in Punch.

The technology did not then exist to bore tube tunnels deep under urban areas, still less to access them via lifts and escalators, nor were there yet the smoke-free electric trains that later enabled deep-level operation. And an 1846 Royal Commission had expressly excluded the building of surface rail lines and mainline stations from much of central London, to avoid disfiguring destruction. Various outlandish projects were proposed to get round these restrictions, including a twelve-mile elevated circular railway, with shops and pedestrian walkways, contained within a glass arcade!

However, the Metropolitan Railway Company scheme that was finally approved by Act of Parliament in August 1859, with a substantial investment from the City of London, was one championed by Charles Pearson, the City’s solicitor. He proposed that connecting prosperous West London with existing mainline stations, and the City where many worked, would ease street congestion and encourage labourers to move out from poor, overcrowded town centre housing.

Charles Pearson (4/10/1793 to 14/9/1862) c.1855. Unfortunately he did not live to see his vision attained.

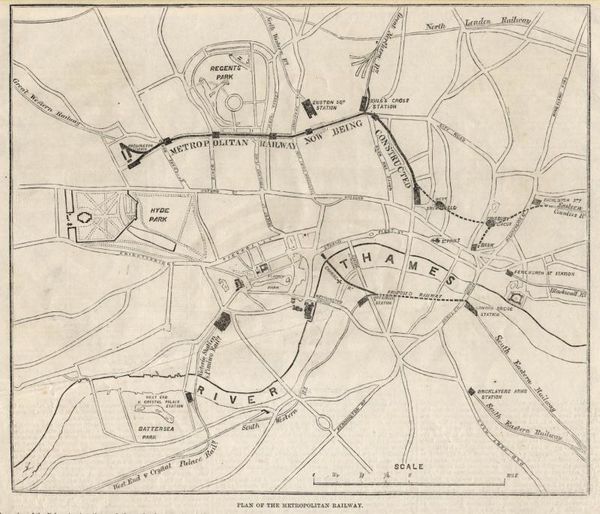

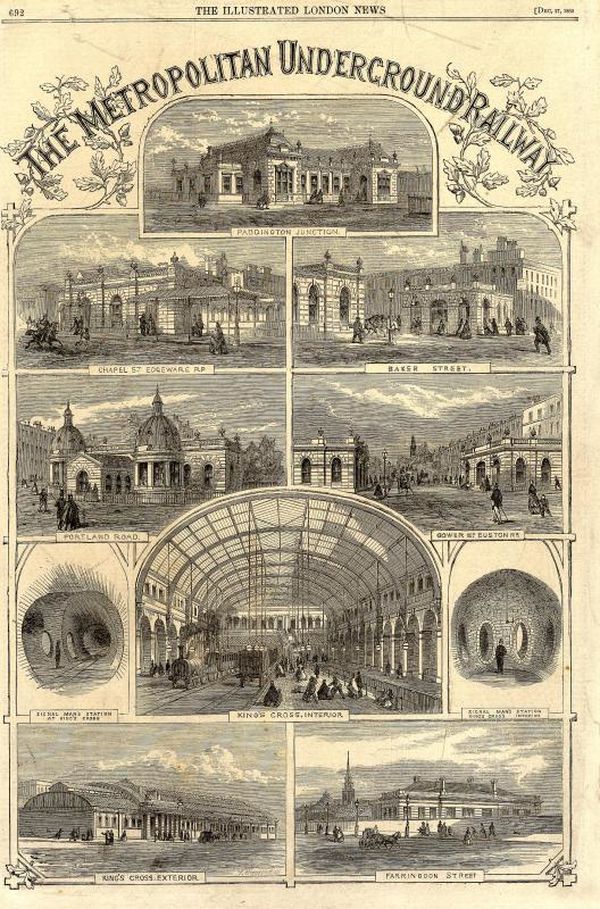

Pearson’s plan was to utilise the straight thoroughfare (often then called the New Road, but more commonly the Marylebone and Euston Roads) for a route passing the mainline rail stations of Paddington, Euston Square and King’s Cross, before proceeding down the Fleet river valley to the edge of the City of London at Farringdon. The stations were to be at Paddington (Bishop’s Road), Edgware Road (Chapel Street), Baker Street, Portland Road (now Great Portland Street), Euston Square (Gower Street), King’s Cross and Farringdon Street (now Farringdon).

Minimum demolition was the aim of the New Road section, “To avoid the necessity of paying compensation for much valuable property,” as the Illustrated Times put it. Such niceties were not, however, extended to the shorter Fleet valley stretch beyond King’s Cross, which would traverse areas of slum housing. Indeed the neighbourhood around Farringdon was described as a “dreary locality”, ripe for redevelopment and “Architectural Embellishment”. (Illustrated Times, 7/4/1860; The City Press 10/3/1860)

Plan of the Metropolitan Railway. Illustrated London News, 7/4/1860.

The New Road cut-and-cover method of construction was an innovative piece of civil engineering. “The bed of a London thoroughfare may be compared to the human body”, observed Charles Dickens’s All the Year Round periodical, “for it is full of veins and arteries which it is death to cut. There are the water-mains with their connecting pipes; the main or branch sewers, with their connecting drains; the gas mains with their connecting pipes; and very often, the tubes containing long lines of telegraph wire…lying as nearly close together as the pipes of a church organ. The engineers of the Metropolitan Railway have had to remove all these old channels to the side of the roadway, steering their tunnel in between, with the delicacy of a surgical operation.” (Reproduced in The Weekly Chronicle And Register, 26/1/1861)

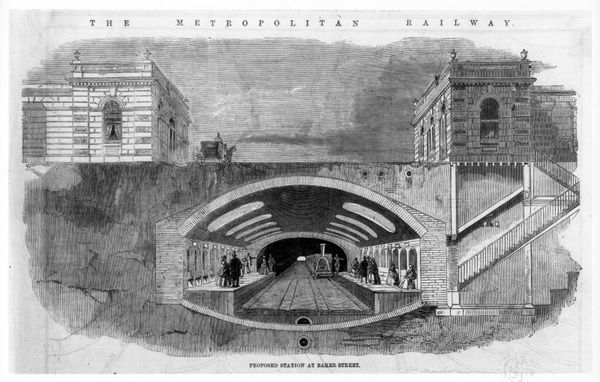

The Metropolitan Railway: Proposed New Station at Baker Street. Illustrated London News, 7/4/1860. This cross-section shows the roadway restored above the tunnel.

Work began in January 1860. A month later the project’s chief engineer, John Fowler, was able to report that matters were well underway at several points, with the stretch from Paddington to the west side of Euston Square contracted to Messrs Smith & Knight and that from there to the City contracted to Mr John Jay. Ominously for some, Fowler also reported that “Notices (which constitute an absolute contract of purchase) have been served upon nearly all the owners of property throughout the line…”. There were of course to be numerous disputes over compensation amounts for requisitioned and damaged property. The West London Observer also speculated that the New Road route “will come into very unpleasant proximity to the houses along the road…”, which proved true. (Herapath’s Railway Journal, 11/2/1860; The West London Observer, 4/2/1860)

Despite its cut-and-cover expedient the New Road section could not do without some property clearances, particularly around the planned stations that required space additional to the line. Notices of Metropolitan Railway sales by auction of building materials from demolished New Road area houses started to appear in the press from May 1860 onwards, and it is clear that many had been quite grand. On 22nd June, auctioneers Pullen and Son advertised building materials from 25 such defunct properties around the planned Edgware Road station for sale on behalf of the Metropolitan Railway directors. Pretty much everything that made for a building seems to have been meticulously dismantled and catalogued, including some “350,000 excellent stock bricks,” and “…several tons of lead in gutters and pipes, iron columns, stoves, ranges, coppers, cisterns, and numerous useful fixtures.” (The Morning Advertiser, 21/5/1860, 1/6/1860, 22/6/1860)

In December 1860, the about-to-be dispossessed proprietor of no. 1 Park Crescent, a smart house listed for removal in the approach to Portland Road station, offered its “elegant and superior modern FURNITURE, new within the last two years” for sale. It was stated that “the appendages for the drawing-rooms are walnut and rosewood,…[there are] costly ornaments, dining-room adjuncts of Spanish mahogany…capital carpets throughout…winged wardrobes, marble-top washstands, Arabian bedsteads…a small but choice cellar of wines etc.,” The Globe was outraged at proposed demolition in this choice locality, “entirely destroying the architectural symmetry of Park Square and Park Crescent”. The next door house was also taken down. These had been part of the architect John Nash’s grand urban remodelling project in regency London.(The Morning Herald, 13/12/1860, 4/8/1862; The Globe, 14/3/1860)

Stations of the Metropolitan Underground Railway. Illustrated London News, 27/12/1862

In July 1860, an Edgware Road gentlemen’s outfitter informed the public that, since his premises were required for the railway, his “extensive stock…will be sold from 20 to 30 per cent. under Manufacturer’s prices,” including, “Hats! Hats! Hats!”. On the other hand, some traders were anticipating a boost in business arising from the underground’s proximity. A 96 year lease on the British Oak public house was offered in October 1860, with the promise that its “commanding position” adjacent to the intended Paddington underground station and opposite the mainline one, “must, within a short period, double the present large and profitable trade…” (The Marylebone Mercury, 28/7/1860; The Morning Advertiser, 15/10/1860)

Many New Road traders and residents, however, were soon bemoaning the disruption that the works inevitably caused, and for which they were to receive no compensation. In early May 1860 a public meeting was held at Frampton’s Music Hall, St Pancras, “to consider what steps should be taken to obviate the serious loss and inconvenience arising from the opening of the Euston-road, each side for the sewerage, and in the centre for the Metropolitan Railway.” Locals complained that “mounds of earth, soil &c.,..thrown up, almost prevented them getting to their houses; that in cases of tradesmen their businesses were brought to a stand”, and that this had gone on for nearly three months. (The Express, 5/5/1860; The Morning Advertiser, 11/5/1860)

An excavation of a cut-and-cover tunnel down the middle of Craven Hill, 1867. 1998/86078 © TfL from the London Transport Museum collection https://www.ltmuseum.co.uk/

Construction work at Craven Hill, 1867. 1998/84471 © TfL from the London Transport Museum collection https://www.ltmuseum.co.uk/

Though taken a few years later, when the line was being extended from Paddington through Bayswater by the cut-and-cover method, the above photos illustrate the kind of conditions that New Road area inhabitants endured.

Some residents and traders formed The Euston Road Trade Protection Association. Its Secretary, William Bilton (whose address was given as 36 Lamb’s Conduit Street, at some remove from the nuisance!) wrote indignantly and at length to the Editor of The Morning Advertiser in May 1860, including this complaint: “The contractors are carrying out the works in the most slovenly manner, and instead of studying the interests of the persons opposite whose shops and residences they have sunk their shafts, they seem rather to have taken pains to render their works as obstructive as possible, in some instances literally to have blockaded the premises, and yet these injured persons are told there is no remedy.” (The Morning Advertiser, 12/5/1860)

But there are worse things than muddied shoes and obstructed shop doorways. On the 8th May, 1860, an eight year-old boy named Andrew Lawford Wall was playing with some other children on one of the mounds of spoil in the Euston Road, “and while stooping to pick up a piece of clay a portion of the mound slipped and the child was pitched head foremost under the wheels of an omnibus passing at the moment, which went over his head, neck and chest.” At the poor child’s inquest the coroner found no criminality involved, but was highly critical of Mr Jay, the contractor on this section of the road for not removing the mounds in a timely fashion. The jury also stated in a special verdict: “that the works where the accident happened have been executed in a careless, unguarded manner, and in a way calculated to endanger human life.” (The Morning Herald, 18/5/1860)

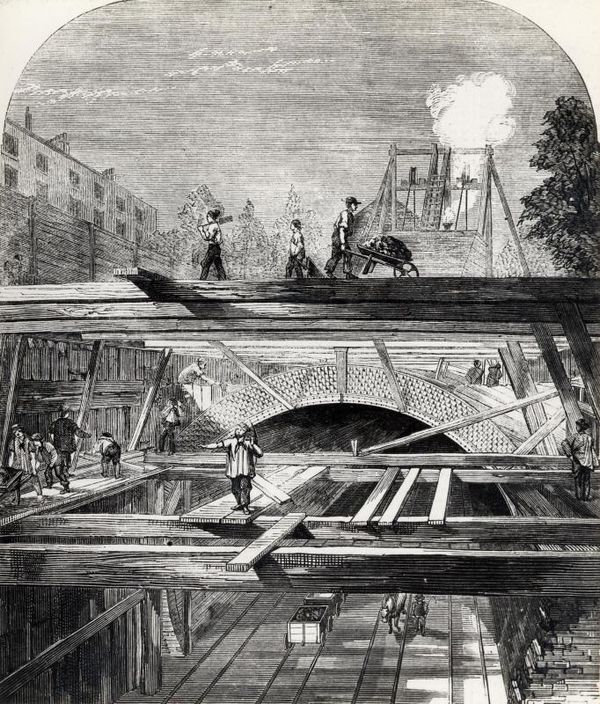

Engraving showing the cut-and-cover method used in the construction of a Metropolitan Railway tunnel. Illustrated London News, 1861. The works look remarkably clean and neat in this representation.

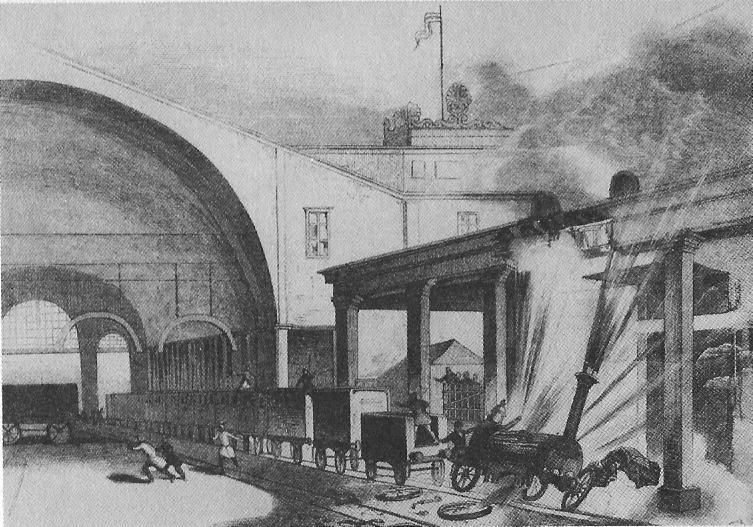

Another fatal accident occurred in November 1860 when the Albion, a locomotive owned by Mr Jay and employed to remove spoil from the excavations via a connecting tunnel to mainline King’s Cross, exploded outside the tunnel entrance: “The buffers were torn off like matchwood, the driving wheels forced from their axles, and the whole engine, a very excellent one, was smashed to pieces. The poor engine-driver was dashed to a mummy, and the stoker thrown high in the air and killed instantaneously. The foreman of the works was also much injured. The shock was heard over the whole of the northern part of the metropolis.” Although the inquest on the deaths of the driver, George Wiggins, and the fireman, Charles Tann, heard that the Albion’s exploded boiler was defectively manufactured, no finding of criminal responsibility was returned. (The Sun, London, 1/11/1860, 20/11/1860)

Steam Locomotive “Windsbraut” (Windbreak) exploding on the platform of Dresden Station in Leipzig, 1846

On the evening of 30th May 1860, a mainline excursion train from the north arrived at King’s Cross station and, “instead of slackening its speed, as is usual on entering the station, actually leaped the platform at the end of it…carrying with it the tender, the break, one or two carriages, and proceeding on in its fearful and precipitous course, ran down the inclined plane immediately under the clock tower and across the Old St. Pancras-road, where it burst through the enclosure of the Metropolitan Railway works…”. The wreckage buried itself in the excavation’s heaped spoil. There were no fatalities, but some fourteen passengers were injured. The fireman jumped clear, and the driver never left his post. Both were uninjured. (The Morning Post, 31/5/1860; The St. James’s Chronicle, 31/5/1860; Bell’s Weekly Messenger, 2/6/1860; Herapath’s Railway Journal 2/6/1860)

The guard in the rear brake van, James Warrener, who was found to have been drunk, had not applied the brake, and was sentenced to two months imprisonment with hard labour. Bell’s Weekly reported that, “The news of the dreadful occurrence quickly spread over the metropolis, and…all the thoroughfares leading to the station became so crowded that Superintendent Loxton of the S division required the assistance of 150 men of the Metropolitan Police force to keep the way open for the ordinary traffic.” Herapath’s Railway Journal commented, “if a Bengal tiger had got loose from its den in the Zoological gardens and made its way through the streets of London, it could hardly have created more sensation or caused greater alarm.” (The Morning Post, 31/5/1860; The St. James’s Chronicle, 31/5/1860; Bell’s Weekly Messenger, 2/6/1860; Herapath’s Railway Journal 2/6/1860)

A fatality was avoided in May 1862 in an incident that may be said to have foreshadowed the many sad instances of suicide under trains which were to occur on the underground. A thirty year old discharged soldier was prevented from throwing himself into the cutting of the Metropolitan Railway at Charlotte Street, St. Pancras by a conscientious railway worker who grabbed his hand and pulled him clear. When charged with attempted suicide the soldier said he had a wound on his head “which sometimes took away his reason.” He was sent to the workhouse. (The Express, 29/5/1862)

In May 1861 there was a major landslip at the Euston Road excavation near Judd Street, through no casualties were involved since the workmen had been evacuated at the first sign of danger. One account of the slip gives an insight into the method of working: “The entire extent of this section is hoarded in up to the pavement; the entire roadway has been gutted out to a depth of 30 feet below the surface and the sides of the road are supported by large bulks or struts of timber. A waggon way is then formed upon rails, and the excavated material…is removed…to make way for a continuous brick tunnel…”. Apparently, “about four o’clock the whole of the earth in front of the pavement on the north side, the pavement itself, and the walls and railings in front of no less than eight houses, fell in with a tremendous crash…the inhabitants rushed out in the greatest alarm.” Remarkably, this seems the only calamity of the sort to have occurred along the length of the New Road section. (Bell’s Weekly Messenger, 25/5/1861; John Bull, 25/5/1861)

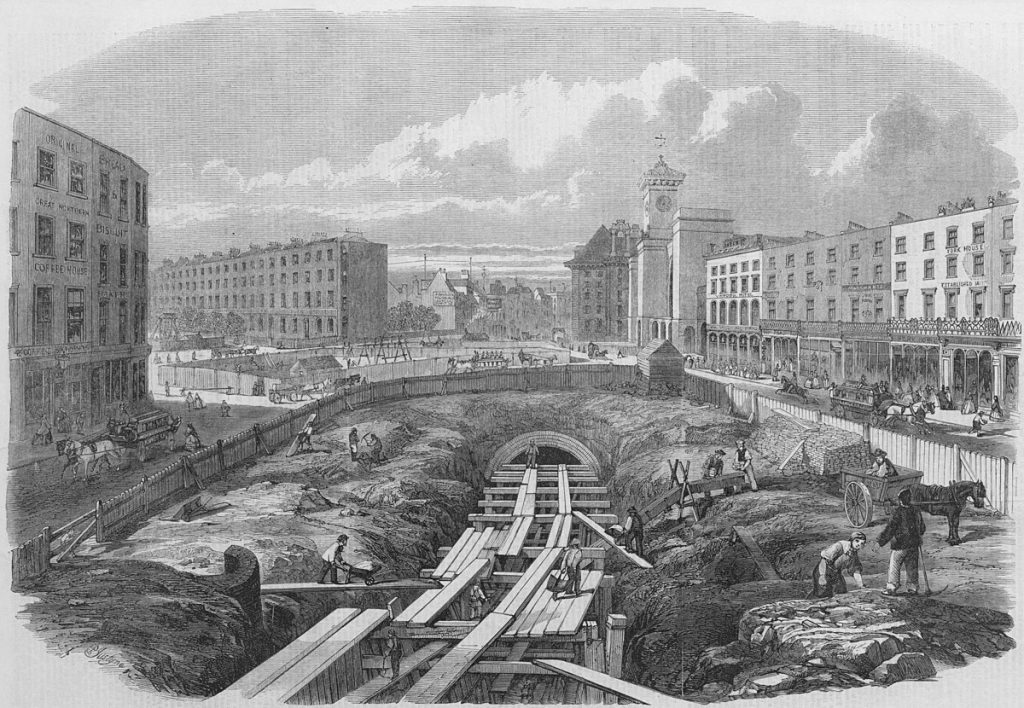

Constructing the Metropolitan Railway. Illustrated London News, 2/2/1861.

The above illustration shows the line under construction as it curved southwards towards the City, just east of King’s Cross station (St. Pancras station was not yet started). This Clerkenwell stretch to Farringdon had no long, continuous roadway to follow, instead it hugged the course of the old Fleet river, which was actually an enclosed sewer-ditch by this time. Since this passed through the “poorest property” of low lodging houses, “the fever dens of the metropolis”, which created little financial incentive to avoid demolition, many obstructing buildings were swept away. An area of poor housing near Farringdon had already been cleared (the new Farringdon Road, which would run parallel with the line, was being developed at the same time). This meant that this section could go through open cuttings for much of the way, without incurring the expense of covering them over. (Herapath’s Railway Journal, 17/3/1860; The Morning Herald, 28/10/1862; Illustrated Times 19/10/1861)

On 19th September 1861 The Morning Chronicle reported that “The Metropolitan Railway is fast eating its way into the heart of the City…and this day has been assigned as the last day of occupation of those who occupy the houses in Acton-street and the other streets branching off the Gray’s-inn-road, which stand in the way of the line.” A week or so later The City Press described how, “the inhabitants of two houses in Exmouth-street, Clerkenwell, and Guildford-place have been ejected on warrants issued by the Clerkenwell police-courts, in consequence of the dangerous state of the structures, which were badly cracked and rendered unsafe, by the works of the Metropolitan Railway. During the past month the Police Surveyor has condemned nearly a dozen houses in Guildford-place.” (The Morning Chronicle 19/9/1861; The City Press 28/9/1861)

In December 1861 two police officers turned a Mr C. Somers, described as “the well-known shot”, and his daughters out of their pub, the Cobham’s Head, Coppice-row, in accordance with a “warrant of ejectment”. The building was described as being “in a very dangerous state” owing to the Metropolitan Railway works, since “the whole of the house is leaning forward into the tunnel.” Somers claimed £1,245 compensation for the loss of his business (he was just a tenant-at-will of the property) but was awarded only £250 by the jury, though he had managed to instruct Mr Karslake, a Q.C., to act for him! Someone stood to derive a greater financial benefit (though it is not recorded who) when, “On pulling down a house in Clerkenwell, for the Metropolitan Railway, the labourers came upon literally a ‘pot of money’ in the shape of a variety of gold coins, including 400 spade guineas in good preservation.” (The Morning Advertiser, 7/12/1861; The Morning Herald, 30/4/1862; The Dial, 31/1/1862)

“The effect of these clearances hitherto,” summarised the writer Percy Greg in an article entitled “The Homes of London Workmen”, “has not been to drive labourers from the centre of the town to the suburbs, but to crowd still more those ‘rookeries’ of lodging-houses as yet undisturbed. The enormous disproportion between London wages and London rents has, in the case of the labouring classes, only been aggravated by the change.” This was a pity, since beneficial relocation of the labouring classes was one of the project’s aims. (The St. James’s Chronicle, 8/5/1862)

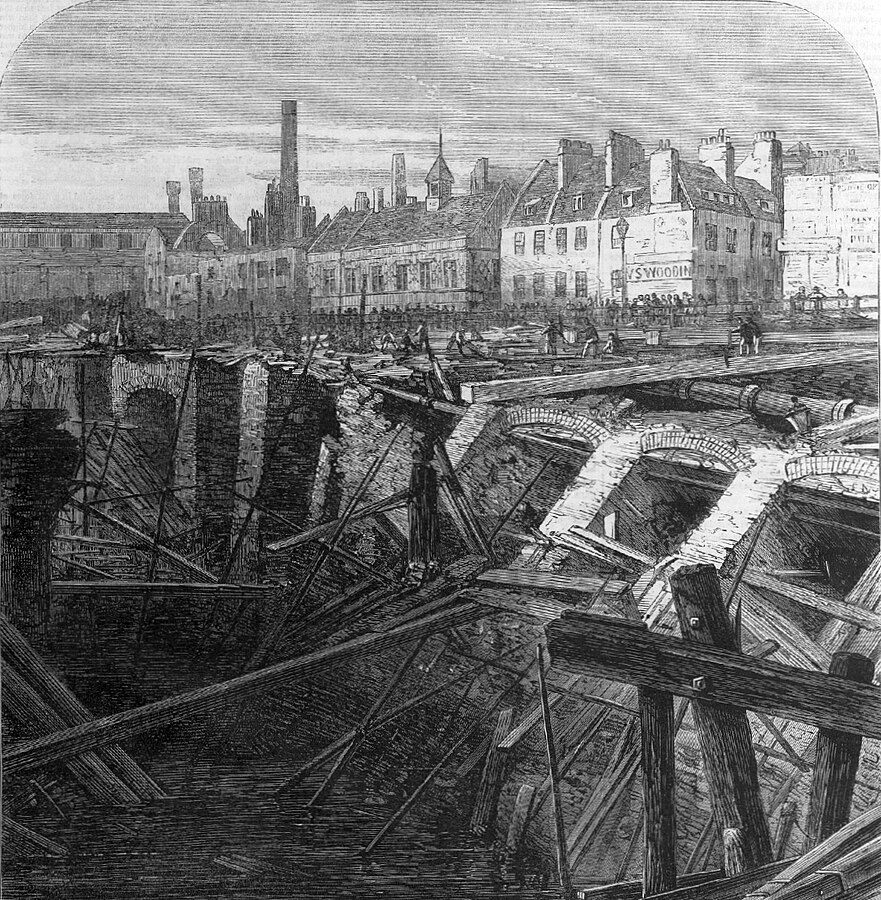

Collapse of the Metropolitan Railway Cutting. Illustrated London News, 28/6/1862. This incident delayed the line’s opening by several months.

Containing the Fleet river was the major engineering challenge on the Clerkenwell stretch. Dickens’s All the Year Round periodical described the river as “a black styx” and “a stream of sewage-water flowing from Highgate to the Thames out of fifty thousand houses.” By January 1861 a necessary diversion of it into a pipe-way over the new line at King’s Cross had been effected, so that “the black river is now safely caged…”. But it was not! Following heavy rain the Fleet-ditch burst on 14th June 1862 near Farringdon, flooding the railway cutting to a depth of ten or twelve feet and causing a section of brick tunnelling and arches to collapse “into a heap of ruins”. At night “immense crowds were assembled looking at the scene of destruction…and a large number of police were required to keep the roughs who abound in that neighbourhood in anything like order.” (The Weekly Chronicle And Register, 26/1/1861; The Express, 19/6/1862)

The “navies” who dug and built the railway, mostly by hand and without machinery, and who had to make-good the above collapse while wading in muck and sewage-water, did not go completely unrecognised at the time. In January 1861 an invitation from the London City Mission to attend an evening’s entertainment at a hall in Marylebone brought forth between two and three hundred of them, “nearly the whole of whom had divested themselves of their working apparel, and had gone through the ablutions necessary to present a clean and decent appearance.” There was tea and cake, an exhibition of “dissolving views” (a magic lantern show), and an illustrated lecture upon the story of Pilgrim’s Progress: “To this great attention was paid, and throughout the entire proceedings the greatest order was maintained.” (The British Ensign, 9/1/1861)

As the work neared completion in August 1862, Smith & Knight, contractors for the western portion of the line, gave a dinner for their workmen at the new Euston Square station. “A platform was erected above the rails, and the walls were gaily decorated with flags and banners. About 600 men sat down to dinner, and were entertained in a very liberal manner, Mr Smith presiding. Various toasts were drunk with hearty good will, and, after some complimentary speeches, the proceedings terminated at an advanced hour.” (The North London News, 16/8/1862)

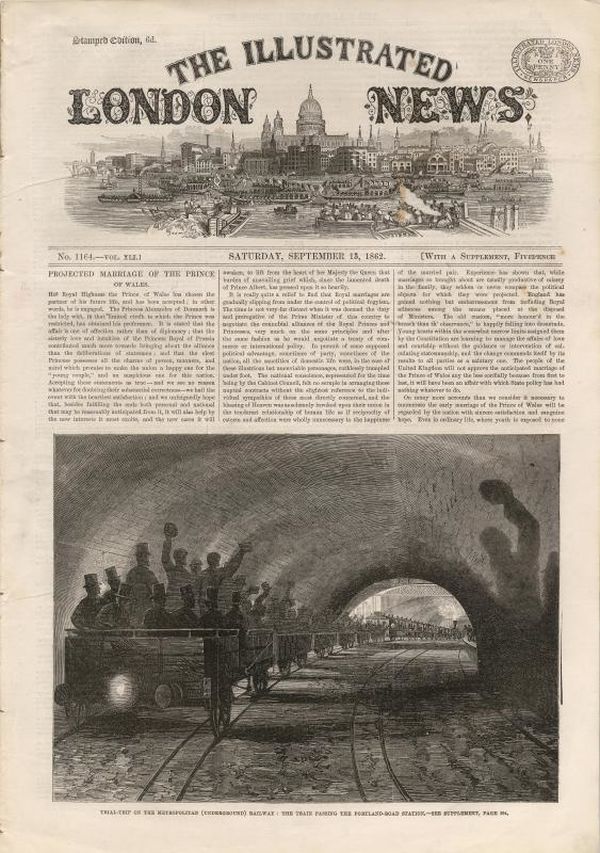

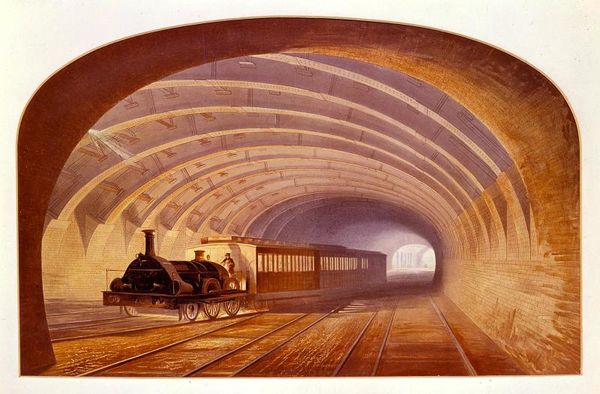

Front cover of The Illustrated News, 13/9/1862, showing: Trial-Trip On The Metropolitan (Underground) Railway: The Train Passing The Portland-Road Station

In September 1862 a large number of Metropolitan Railway Company shareholders and representative of the parishes through which it passed were conveyed the length of the completed line. The above illustration shows rails laid for both narrow and broad-gauge stock, since both were used initially. Only the rear coaches were open on this trip, and when the line opened all its coaches were enclosed.

On Friday 9th January 1863 an inaugural train conveyed an assemblage of distinguished persons from Paddington to Farringdon for a ceremonial opening, “where the band of the metropolitan police force welcomed the arriving visitors with the popular air of ‘See the conquering hero comes’. Here the station was very tastefully fitted up as a banqueting hall, to accommodate between 600 and 700 persons… The proceedings passed off with the greatest eclat. (Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper, 11/1/1863)

After the line opened to the general public on Saturday 10th January, 1863, The West London Times commented: “It was continually asked, would people, accustomed to the light and (stuffy) air of omnibuses, ever consent to drive underground?…Last Saturday solved the riddle. The Underground Railway did not require touters outside earnestly entreating passing passengers to descend, and take their places in the cellar station; the crowds who were anxious to try the results of the latest experiment in railway making far exceeded the accommodation provided…The Underground prejudice disappeared as soon as the doors were open…” Though finished behind schedule (chief engineer John Fowler had expected it’s completion in twenty-one months), the three and three quarter mile stretch had still only taken three years to build. (The West London Times, 17/1/1863; Herapath’s Railway Journal 11/2/1860; The St. James’s Chronicle, 8/4/1862)

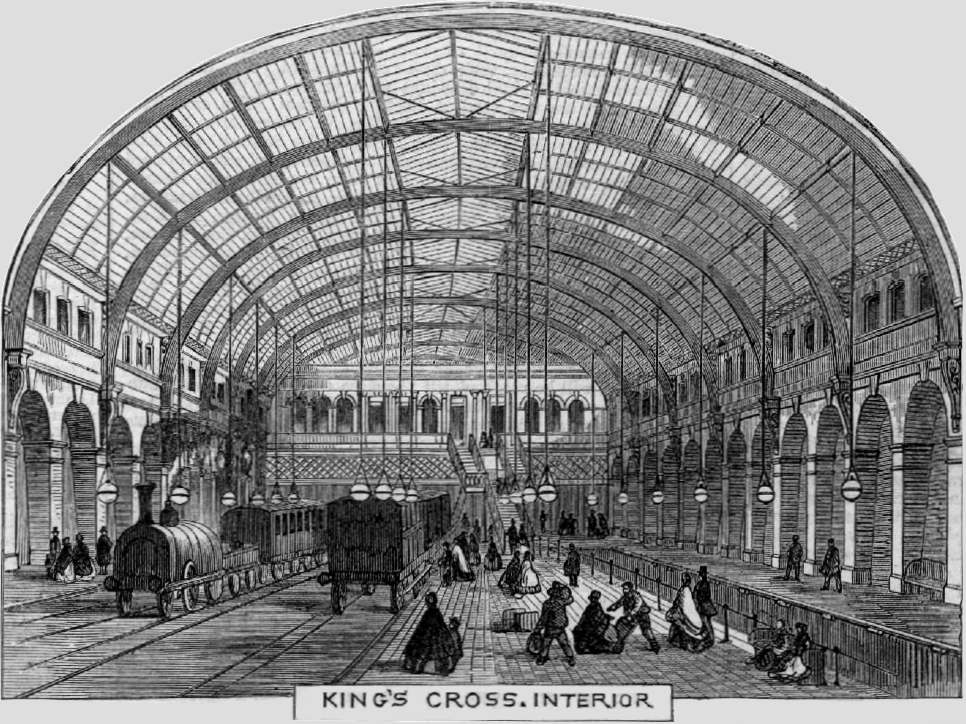

Interior view of King’s Cross Metropolitan Railway Station, Illustrated London News, 27/12/1862

There were initial troubles due to overcrowding and inadequate ticket-issuing provision. Smoke and steam from the locomotives could create “a deadly atmosphere”, and this continued to be a nuisance, despite efforts at amelioration, until electrification in 1905. There were vibrations caused to buildings above, which continue to this day! But passenger numbers totalled about 225,000 for the first week, spread fairly evenly from day-to-day, and the line was soon being widely extended. From six in the morning to midnight on weekdays, trains at first ran in both directions at intervals of a quarter of an hour or twenty minutes. On Sundays the service ran from 8 am until 10:40 pm. There were three classes of travel, though the cheapest at threepence one way and fivepence return was not that cheap. However the introduction of early-morning reduced cost workmen’s trains in 1864 proved very successful. (The Weekly Dispatch, 11/1/1863; The Evening Standard, 12/1/1863; The Morning Post, 23/1/1863; The British Ensign 21/1/1863)

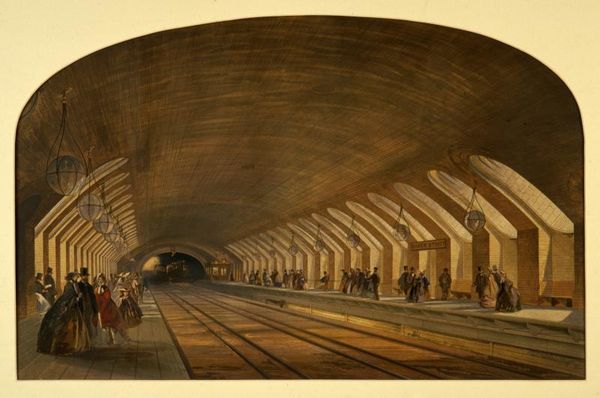

View of a broad-gauge steam locomotive hauling a train approaching the platform at Baker Street. The scene at Baker Street is still recognisable today, 160 years later. Light entering from the ventilation shafts can clearly be seen, though the shafts have long since been blocked up.

The Morning Post highlighted some of the initial problems on 23rd January 1863, particularly those caused by smoke, but also wrote that: “The company, as far as they have been able, have ministered most successfully to the comfort of their passengers. The carriages are lofty, commodious, and brilliantly lighted. The line is admirably laid down, and…we glide easily over it.”

The Christian World was more glowing still, writing on 16th January 1863 that it “really it is not the dark and dismal affair which the unbelievers in the possibility of building it imagined, but a thing of elegance, beauty and comfort, quite inconceivable for an underground railway.”

Broad gauge loco “Hornet” pulling a passenger train at Praed Street junction on the Metropolitan Railway.

I am indebted to the British Newspaper Archive for access to the above articles, as identified by publication and date:

https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/

Other Reading:

Christian Wolmar, The Subterranean Railway, 2004

Oliver Green, London’s Underground: The Story of the Tube, Updated Edition

Another brilliant and expertly researched piece Mr Croft! Do you happen to know the provenance of the golds coins and guineas?

– Rog.

Very interesting…most people tend not to think or be aware of how our present came about.. thank you

Very interesting article Mr Croft. Be interesting to know a bit more about the actual civil engineering aspects of constructing the line as this would have presented numerous challenges.

Absolutely fascinating! I’m amazed at tge sheer ambition of the project, let alone the actual construction of it!