My cultured friend and I recently visited Sambourne House, a West London terraced home preserved pretty much as it was in the 1890s, complete with its original contents and furnishings. We have all trailed around aristocratic country mansions, but what is so rare (perhaps unique) about the preservation of Sambourne House is that it was the comparatively modest home of a middle class family, albeit a prosperous one. This gives the visitor a real sense of how it might have been to live there in past times, which is often hard to capture amid the overwhelming scale and grandeur of a stately home.

The exterior of Sambourne House – Courtesy of: 18 Stafford Terrace, Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea

Glazed fern cases, like the one attached to the ground floor bay window, used to be standard fittings, as did the large gas lamp above the front door with the house number on it. From pavement level little details stand out, such as the separate bell-pulls for trade and social callers, or the sign on the door that can be alternated to show that the master of the house is “in” or “out”.

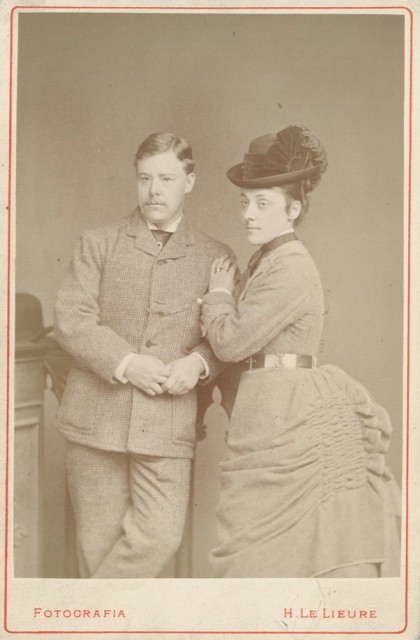

The house’s occupants were Linley and Marion Sambourne (with the later addition of their children Maud, born 1875, and Roy, born 1878) who moved in upon their marriage in 1874. Linley was a cartoonist, illustrator, and photographer, whilst Marion was the eldest daughter of a stockbroker. From 1882 both kept diaries, so that the pleasure of exploring their house can be enhanced by reading about their daily lives there.

Linley (1844-1910) and Marion (1851-1914) Sambourne – Courtesy of: 18 Stafford Terrace, Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea

On entering the hallway, one is immediately struck by how richly the house is fitted out. The back of the terrace is south-facing, and bright sunshine can be seen washing into the landing at the head of the first flight of stairs (see below). My cultured friend said that she would like to sit by the fish-tank on the landing and read in the afternoons if the house was hers (some hope!). Parts of the interior are unavoidably gloomy, due to the browning of old fabrics and old wallpaper (some by William Morris!) but this just adds to the authenticity. Little details are again to the fore, such as the case containing umpteen walking sticks.

The Hallway – Courtesy of: 18 Stafford Terrace, Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea

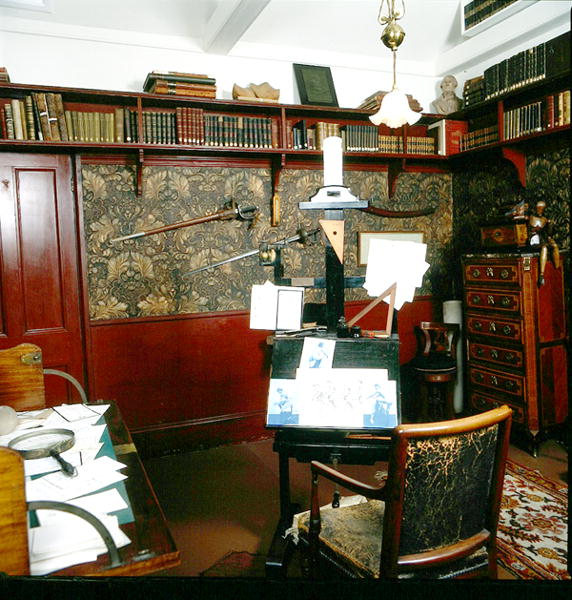

The first door from the hall on the right (above) leads into the dining room, and the second into the morning room (which was Marion’s own preserve). Up the stairs the drawing room takes up almost the whole of the first floor, from the bay to the back windows. Stepping inside this room, it is clear that the notion of the cluttered Victorian interior is no myth. Little of the floor space, shelf space or wall space is exempted from supporting some class of object. Linley Sambourne worked at home, initially at the south end of the drawing room. In later years the attic was modified to create a purpose-built, and better-lit studio for him to use.

The Studio – Courtesy of: 18 Stafford Terrace, Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea

Like Henry Mayhew, Arthur Munby and Hugh Shimmin, of whom I’ve written elsewhere in these pages, Linley Sambourne was an observer of his times. He differed from them in being an artist rather than a writer, but also in not sharing their preoccupation with the lower elements of society. For the bulk of his professional life, Sambourne drew cartoons for the humorous weekly magazine Punch. This has been out of publication for a few years now, and it is hard to imagine just how widely circulated and influential such a periodical was amongst the middle and upper classes in its heyday. Sambourne’s intricate and detailed weekly cartoons were keenly awaited, and his was a household name. In 1901, he succeeded Sir John Tenniel (author of the brilliant “Alice in Wonderland” and “Through the Looking Glass” illustrations) as “First Cartoon” at Punch.

After he discovered photography, Sambourne dragooned anyone and everyone who appeared at the house (including himself, his groom and the local beat-policeman) into costumes and funny poses to be snapped as models for his drawings. Later, as the technology of photography became more mobile, he amassed an archive of studies taken out and about in the streets, mostly of young women in everyday clothing (it seems that there was also an archive, taken indoors, picturing young women in less, or no clothing.)

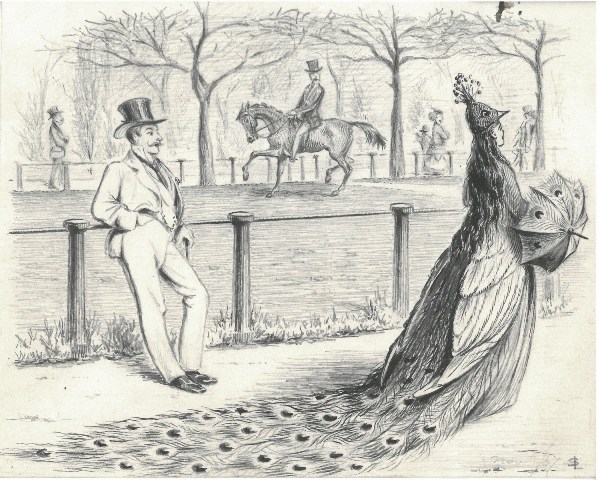

As his subjects were mainly the politics, personalities and current affairs of his day, the thrust of Sambourne’s cartoons can be obscure to the modern reader. He was a satiric commentator, not a campaigner, observing the privileged echelons of society (of which he was a member). This is perhaps encapsulated by an early cartoon of his, often referred to as “The Peacock Dress” (see below). The pictured gent is probably leaning against the rail of Rotten Row, in Hyde Park, where society’s glitterati paraded on horseback in the summertime London social “season”.

Miss Swellington Takes a Walk, 1867 – Courtesy of: 18 Stafford Terrace, Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea

Sambourne was an incorrigible bon viveur, and he died in 1910 from the cumulative effects of excess food, drink and tobacco. Their daughter Maud was a joy to her parents in many respects, marrying well, producing a brood of children, and being careful of her parents’ well-being. However, the verdict on their son Roy is not so rosy. It seems he suffered from profound mood swings and an unstable temperament. He found it hard to settle into anything. As a young man Roy was much in company with pretty actresses, to his parents’ disapproval, admiring them rather like the gent was doing in the cartoon above, looking at the girl in her peacock dress. Roy did not marry and lived on alone in the house until 1946, dying thirty-two years and two world wars after his mother had passed on in 1914. He made no alterations to the house over that period, and the walls of his bedroom remained adorned with portraits of the actresses he had known in his youth, each affectionately signed to his dedication (one is signed by “the babe”). This must have been rather poignant for a solitary individual, as he aged.

Roy’s Room– Courtesy of: 18 Stafford Terrace, Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea

So, in a way we have Roy’s loneliness and inertia to thank for the survival of the house in its original form. It passed to his sister Maud on his death, and she in turn wanted it to stay as it had been in her parents’ time. Her daughter Anne, Countess of Rosse, used it as a London pied-à-terre, and in 1958 founded “The Victorian Society” in the drawing room there. The house is now administered by the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, whose diligence in maintaining this priceless relic, and facilitating access to it, is to be thoroughly applauded. It is very well worth a visit.

I am grateful to “A Victorian Household” (1988) by Shirley Nicholson for much of the factual information about the Sambourne family and house included above. Also to the guide in period costume who showed us around, and to the RBKC website on the subject.