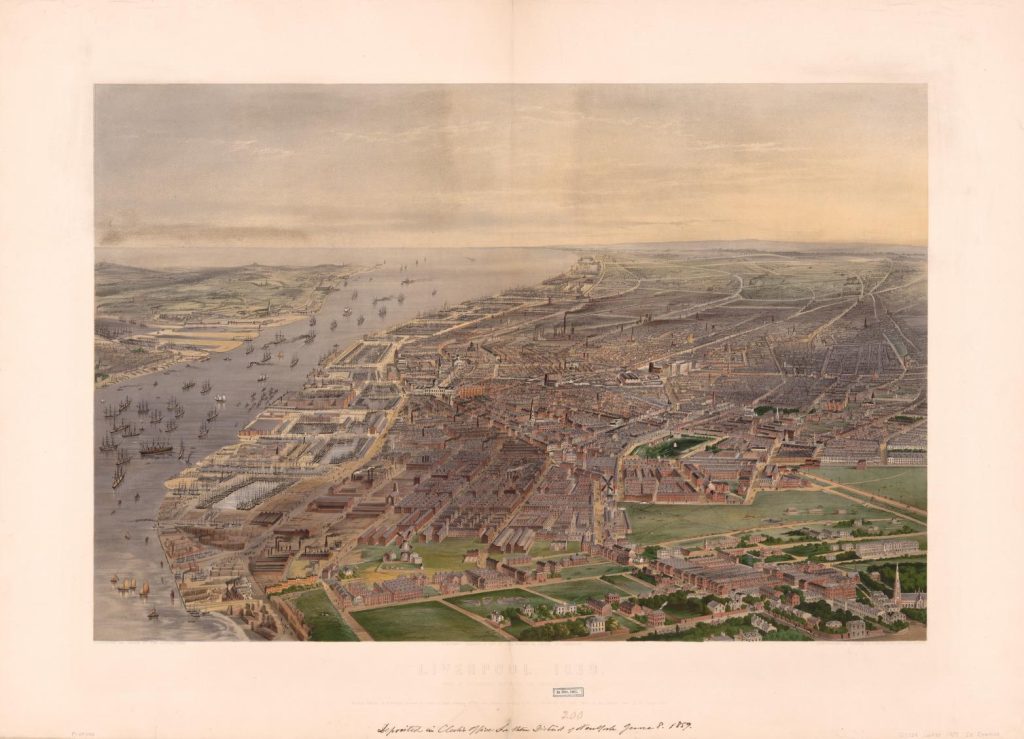

Liverpool’s waterfront must have been a fascinating place to visit in the first half of the Nineteenth Century. The growth of the dock estate in the period was prodigious, and by now Liverpool was second only to London as the chief port of empire. Ships, goods, merchants and sailors from all over the world packed its quays, warehouses and lodgings, and dozens of ancillary maritime trades and professions competed for business. But, just as sea-passage was extremely hazardous at a time when wooden sailing vessels still predominated, so passage through the port itself presented multiple perils to the seafarer, as I shall explore in this post.

Liverpool 1859. John Raphael Isaac. By this time the docks stretched along the river Mersey from “Brunswick” in the south to “Canada” in the north.

On the 23rd April, 1841, The Liverpool Standard reported that: “On Wednesday, at noon, (shortly after high water,) the river presented one of the most interesting marine spectacles ever witnessed in this or any other port. The day was fine, with a fresh breeze from the N.E., favourable for vessels going down the channel coastwise (southward), or seaward, and a vast number of craft of all descriptions consequently pushed out from the several docks into the stream, until the bosom of old Mersey bore a fleet which alone would have done honour to any maritime state in Europe.”

However, for inward-bound sailors the perils of their passage through the port began at the very dock gates: “It is not perhaps so generally known as it should be,” cautioned the Standard, only a few weeks before its celebratory account above, “that numbers of crimps and lodging house keepers of the lowest class make a practice of forcibly intruding themselves on board of vessels while they are being worked from the peirheads to their berths in the docks. These parties frequently conduct themselves in the most insolent manner to those who are in command, and persist in pursuing their vocation of kidnapping the poor sailors, whom they frequently contrive, on such occasions, to render unfit for duty by clandestinely supplying them with spirits.” (The Liverpool Standard 26/03/1841)

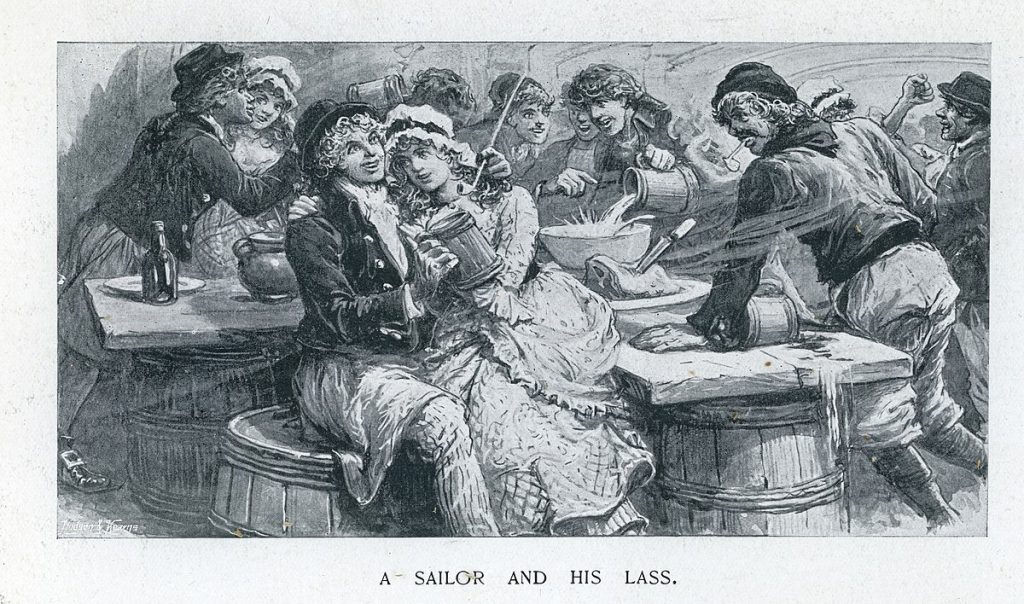

The practice of “crimping”, whereby sailors were decoyed, usually by women, under one pretence or another in order to rob them, was widespread. In May 1841, Antonio Maria Dacros, second engineer of the steamer Oporto, lying in the Trafalgar Dock, went with a fellow Portuguese man to a tavern near the dock, where they met Rachael Pixton, “a handsome, but slovenly-attired young woman…”. So enamoured were they with hers, and another young woman’s society, that they eventually accompanied them to a house in Harrison Street. “In the morning the females were missing, and Dacros found that he had been robbed…of 50 sovereigns, 3 gold pieces…3 crowns, 20 shillings in silver, several Portuguese coins, a gold breast-pin, and a silver snuff box.” Pixton was soon apprehended and admitted the offence, while bemoaning that, “The money is all gone…”. (The Liverpool Standard 8/6/1841)

A Sailor And His Lass. Charles Joseph Staniland.

Drink was generally involved in such occurrences, but a variation on the theme was practised upon an American visitor in 1833. The man had come to England to dispose of some property in Kent, and, having done so, returned to Liverpool with a view to taking ship home, and with the sale proceeds amounting to £93 in sovereigns in his pocket. While strolling along the Goree Piazzas he fell into conversation with an apparently friendly stranger, who invited him along to a pub which turned out to be some distance away in the backstreets. There they had a drink of ale, and met with some other men, subsequent to which the American “recollects no more of the circumstance; but a few hours afterwards he found himself in the streets, minus £93…It is considered that the villains, who were confederates, had, what is termed hocussed the ale, viz. put laudanum in it.” The conspirators were not found, as their victim lacked even the faintest idea of where he had been taken to. (The Liverpool Standard 13/12/1833)

Another American visitor proved far less passive the following year, when, having “overstepped the boundaries of the temperance society and those of prudence, [he] awoke, and found himself, ‘by accident,’ in one of those numerous houses of iniquity, in Poynton-street, frequented by disorderly females.” Finding himself robbed of 41 sovereigns and the house deserted, “the Yankee hit on an expedient to compensate himself for his loss; for, finding the house tolerably well furnished, he went out and hired a porter’s cart, and carried away every vestige of household furniture found on the premises, from the feather bed to the fryingpan.” His initiative, however, was not rewarded, since he had to restore the goods to the landlady in the absence of proof of her complicity in the crime. (The Liverpool Standard 27/05/1834)

It was to provide inexpensive accommodation for sailors, removed from crimps and the blandishments of pubs and “houses of iniquity”, that the Sailor’s Home was opened in 1850 in Canning Place, behind the Customs House.

Liverpool Sailor’s Home, Victorian illustration, circa 1860. Sadly, the building was demolished in 1974.

The many emigrants passing through Liverpool in these years were especially vulnerable to the attentions of swindlers. The Standard reported in April 1834 that nearly 4,500 persons had embarked at the port for America and Australia in the first three months of that year alone. Lone travellers were often robbed in the casual ways described above, but sometimes frauds were more systematic. In January 1834, the Standard complained that, from June the previous year onwards, passage money had been taken from 34 persons boarding the brig Mountaineer, supposedly bound for New South Wales,“each succeeding victim being promised immediate despatch…yet the vessel is still in the Liverpool docks, with her passengers on board.” The paper described conditions for these unfortunates, fast running out of money and provisions, as constituting“a scene of disgrace and misery”, and referred to “the race of low crimps concerned in this kind of business.” Financial subscriptions from concerned citizens were sometimes raised to ease the plight of such people, as was the case for those stuck in port on another emigrant ship, the Cumberland, at around the same time. (The Liverpool Standard 08/11/1833, 15/11/1833, 06/12/1833, 21/01/1834, 15/04/1834, 27/04/1841, 11/06/1841)

The Last of England. Ford Madox Brown, 1855. The Pre-Raphaelite artist depicts a couple with their baby, leaving to start a new life in Australia and not looking back.

The Emigrant Ship. Charles Joseph Staniland

A risk that some might actually choose to run on arrival in port was being caught smuggling. Captain James Morrison of the ship Lord Selkirk, lying in Brunswick dock, was charged in November 1836 with having eight pounds of tobacco and three quarts of brandy “concealed between the timbers. The prisoner, on being questioned, said he had stowed the tobacco and brandy away in order to prevent his mate and second mate from getting them, as they were much addicted to spirits.” Despite this highly inventive excuse he was convicted, and fined £100. (The Liverpool Mail 24/11/1836)

David Clarke, chief mate of the ship British King, in from Havana early the next year, rivalled Morrison in excuse making when he admitted stowing a large quantity of cigars and tobacco in his berth and behind a “false fitment”. He was convicted and fined, despite pleading “that he purchased the goods as a small venture, having a wife and large family. The proceeds, he thought, would have assisted him much, while they would not have been any great loss to the government.” (The Liverpool Mail, 2/02/1837)

Smugglers. George Morland, 1792.

Other types of dishonesty were practised by some “seamen” on ship-masters themselves. Captain Moornan, of the ship George Gordon, was summoned before Liverpool Police Court for non-payment of two crewmen’s wages in January 1837. He pleaded in his defence that the first claimant, an “able seaman”, was in fact an “impostor”, who “could neither steer nor heave the lead, and did not know a rope in the ship”. The second man was hired as cook, “spoiling the sailor’s mess several times, and preparing for them pea-soup made with salt water”. Both claims for wages were dismissed. In January 1841, a certain John Duff was charged at the Police Court with “having accepted several engagements to go to sea, but after receiving monthly notes from the parties respectively, got them cashed, and refused to proceed on any voyage whatever”. (The Liverpool Telegraph 4/01/1837; The Liverpool Standard 15/01/1841)

Some impostors, however, were a good deal more useful. In 1841“A Would-Be Sailor”, named Isabella Stewart, “a healthy stout female, 16 years of age, shipped in Liverpool [aboard the Algonquin, as “Billy Stewart”] as a sailor boy, being dressed in the habiliments, neatly rigged from top to toe, and actually performed the duty of a lad aboard, going aloft, &c., for several days” before the truth was discovered. In early 1842, a young woman named Elizabeth Hunter shipped to Glasgow in the guise of a sailor boy, then reshipped back to Liverpool on a schooner under the same pretence. The captain of the latter vessel “says she is an excellent sailor; and, indeed, her merits have been well tested as there were only three hands on board, she had amongst other duties to reef topsails, which she did in gallant style”. (The Liverpool Standard 3/09/1841, 22/04/1842)

Ship on Fire at Night. Charles Brooking.

Fire was an ever present danger in the docks. One Sunday evening, in January 1842, “a fire was discovered in the hold of the schooner Sarah and Ann, from Waterford, laden with grain, rags, furniture, and tallow, lying in the King’s Dock. The officers on duty sent instant intelligence to the Fire-Police Station…In a short time no less than nine engines were ranged on the dock quay opposite the spot where the vessel was lying. Hose were conveyed on board; and…water was poured freely into the hold, where the heat and density of the vapour indicated, that, if any time were lost, serious consequences might ensue. As the wind was blowing with some violence from the northwest, and the schooner was surrounded by large ships, some of which were laden with spirits, cotton, &c., the consequence of the fire obtaining anything like head would…have been most disastrous.” Fortunately, things were brought under control in a timely fashion. (The Liverpool Standard, 18/01/1842)

The engineer of the appropriately named steamship, Vulcan, was fined in 1837 for allowing the chimney of his vessel to be on fire, throwing out sparks that endangered surrounding craft in the Clarence dock. In 1841 a Customs House officer was fined ten shillings with costs at the Police Court, and strongly reprimanded, for smoking a cigar around some crates packed with straw. A boatman named Hugh Weakley was fined the same sum later in the year for “smoking his pipe while he was landing some kegs of gunpowder at the Seacombe Slip, north-end of Prince’s Dock…”. The magistrate “remarked that the practice was a most dangerous one: it was a wonder, indeed, that the offender and those near him were not all blown in the air.” (The Liverpool Mail, 24/08/1837; The Liverpool Standard 9/02/1841, 16/03/1841)

Shipwreck by storm and misadventure was as much to be feared on the river, and even when berthed in the port, as out on the open seas. There was a “Dreadful And Destructive Hurricane” in January 1839, whereby:“In every dock the damage has been enormous, from the vessels pitching violently against each other, thus staving in their bows and sterns. On the river and the adjacent coasts, the disasters have been numerous and awful… many vessels in the river, utterly helpless, were driven about at the mercy of the tempest.” (Gore’s General Advertiser, 10/01/1839, The Liverpool Mail, 10/01/1839)

The Shipwreck. J.M.W Turner, 1805.

An added peril in the docks and the surrounding sea-lanes was that of collision. One day in January 1842, “the town and river were enveloped in a thick fog, which, as the afternoon advanced, increased in density…the mist became almost impenetrable, especially on the water…The ferry steamers were provided with lights and bells…and on the slips on the opposite side bells were kept ringing or horns blowing.”. Despite these precautions, “about five o’clock the Egerton steamer, which was on her way from Runcorn, with a crowd of passengers, ran foul of a schooner, which was lying at anchor opposite George’s Pier-head. The concussion was so great that the steamer had one of her paddle boxes and mast swept away, and, before she got clear, lost all her bulwarks. The passengers were filled with alarm, and many of them jumped on board the schooner, and were left there. In the confusion one woman was seen struggling in the water, and as no effort could be made to save her, she, no doubt, perished. (The Liverpool Standard, 21/01/1842)

Fatal falls were also all-too-frequent occurrences. In October 1833 a fourteen year old lad overbalanced on the main yard of a timber ship in the Brunswick dock “and fell upon the deck, a height of about thirty feet, and was almost instantly a corpse, having fallen upon his head.” Later that month a fifteen year old boy drowned in the same dock, having fallen overboard from a rowing boat. In November of that year a seaman aboard the Anne Paley, lying in George’s dock, “missed his footing and fell to the deck, from the height of about 49 feet….and was conveyed to the Infirmary, where he breathed his last…” A sailor named John Welch occasioned his own demise when, in June 1836, he attempted to board his ship, the Othello, lying in Prince’s dock, while intoxicated, and fell into the water to drown. (The Liverpool Standard 1/10/1833, 29/10/1833, 5/11/1833, 7/6/1836)

Found Drowned. George Frederic Watts, 1867.

The causes of some of the frequent drownings reported were more mysterious. The case of an unknown male whose body was dredged from the river in May 1840 is rather poignant, since so many details of his ostensibly well-healed life were present: “There were found upon him, a tobacco pouch, a halfpenny, a pearl-hafted knife, a pair of black leather gloves, and a handkerchief. He had on a little black frock coat, drab trowsers, dark waistcoat, black silk handkerchief, linen shirt, and flannel singlet, a pair of shoes, that appeared to be nearly new, and light-coloured knit stockings. He appeared to be from 56 to 60 years of age, light complexion, gray hair, and a little bald. He also had a mark on his chin, which appeared to have been an old cut, and was about five feet 8 inches…in height.” Who was this man, and how did he end up dead in the river? (The Liverpool Standard 26/5/1840)

Not all falls ended in tragedy. An instance of “Praiseworthy Intrepidity in Saving Human Life” arose in April 1841, “when a woman fell overboard from a steamer going out of the Clarence Dock. Captain Cleland, of the American mail steam ship Britannia, being, by chance, on the quay at the time, and hearing the screams, gallantly jumped into the water, fully dressed as he was, and kept her afloat until he made a rope fast around her, by which she was hauled on board the steamer again.” (The Liverpool Standard 9/4/1841)

Captain Cleland’s vessel, The Royal Mail Steamer, Britannia. Owned by the British and North American Royal Mail Steam Packet Company, later Cunard, she carried mail to North America under a government-subsidised contract.

Notwithstanding the assorted calamities and dishonesties depicted above, salvation through acts of selflessness such as that of Captain Cleland was not uncommon. Some months later, by their “bold and humane conduct”, the men of a small fishing smack out of Hoylake saved the lives of the crew “clinging to the rigging” of a schooner named Louisa, wrecked in a gale on the north bank of the Wirral, near the Mersey’s mouth: “It was impossible for them to come near the wreck, in consequence of their own disabled state and the tremendous height at which the breakers of the bank were running; but two of the crew put themselves into their own small boat, having stripped themselves to their shirts, made their way through the breakers, succeeded in reaching the wreck, and returned to their own vessel with the whole crew of the Louisa. (The Liverpool Standard 6/08/1841)

It was all part of the romance, danger, squalor and nobility of engagement with the sea. Visiting future Prime Minister, Robert Peel, who was himself a Lancastrian, was stirred to declare in a Liverpool Town Hall oration in 1828: “I have passed the day in witnessing the wondrous scenes which Liverpool presents; and I have been gratified, astonished, and…surprised, at what everywhere met my eyes. I have frequently heard of the rising greatness of Liverpool, but I never conceived that it had vaulted to such an eminence as it now proudly and magnificently holds.” (The Star 11/10/1828,)

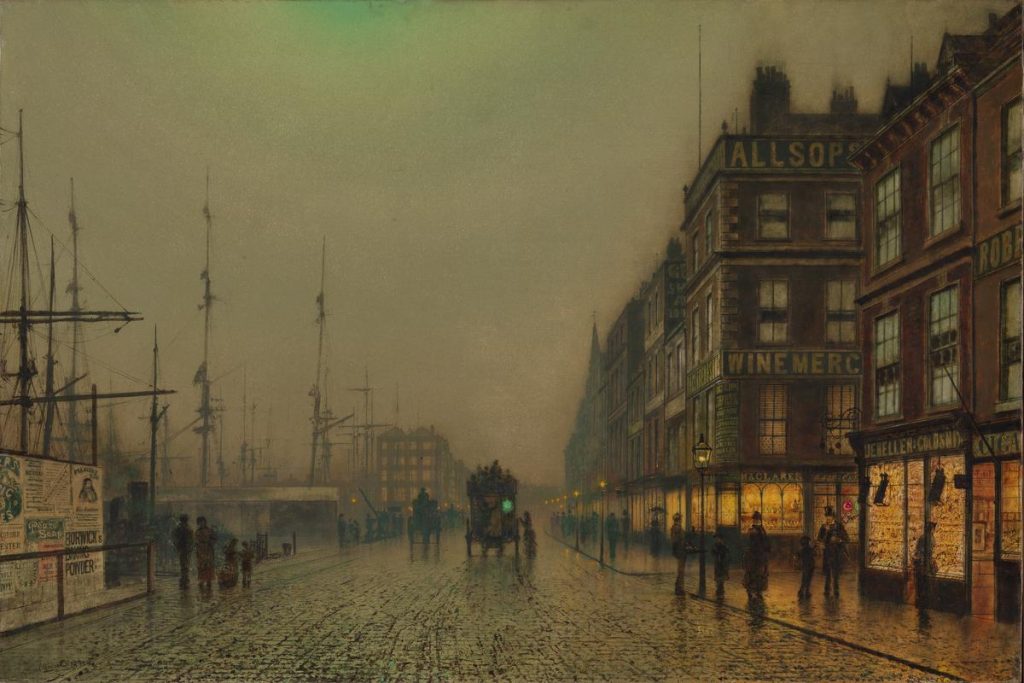

Liverpool Quay by Moonlight, 1887, by John Atkinson Grimshaw.

At Liverpool Docks. Eduardo de Martino.

I am indebted to the British Newspaper Archive for access to the above articles, as identified by publication and date:

Thank you … very enlightening….

Must have been exciting and dangerous times….

The making of a person.

You do wonder whether some sailors were not actually innocent victims looking to have a half of bitter while they were prudently saving their cash, but instead as members of an uncertain and dangerous trade, looking for a kind of pact where they would exchange their back pay for a couple of weeks of sexual, emotional and alcoholic excess before signing back on for another 18 months at sea.

Still of course victims. Perhaps more so, as they aren’t just robbed, but betrayed.