The London Docks were built in Wapping and neighbouring Shadwell, just downstream of the City of London, between 1801 and 1815 by the London Dock Company. First opened in 1805 the docks gave the area a distinctly maritime flavour, since it became a classic “Sailortown”, filled with boarding houses, pubs, beer-shops, brothels and other helpful facilities for the resting seaman. In this piece I shall portray the district in all its often sordid, but colourful, variety as described in press reports from the first half of the Nineteenth Century. I shall also show how the docks faced outward to the wider world, and say a little about what remains of them.

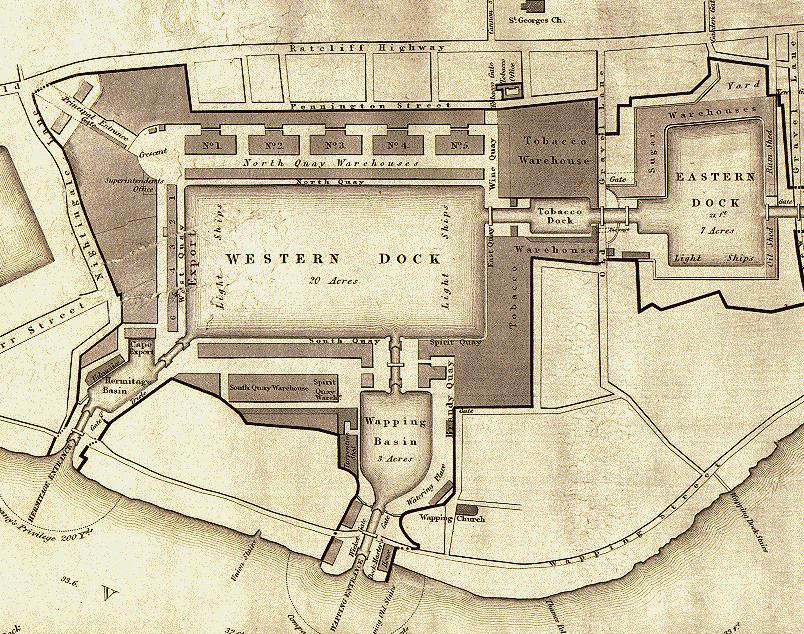

Plan of London Docks by Henry Palmer, 1831. Wikimedia Commons.

The above plan shows the dock complex at its greatest extent, with the Western and Eastern basins linked by the smaller Tobacco Dock and accessed from the Thames by the Wapping and Hermitage basins (though the Shadwell basin which connected eastwards to the river is not shown). The docks covered 90 acres, of which about 35 were water. A corner of the separate St Katherine Dock, opened in 1828, appears to the west. Ratcliffe Highway, the main thoroughfare into and out of the City of London, ran parallel to the dock’s northern perimeter, and Wapping High Street and Wapping Wall curled round behind warehouses along the Thames shore. These sail-ship docks were relatively small in comparison to ones built later further east, and they eventually closed to shipping in 1969.

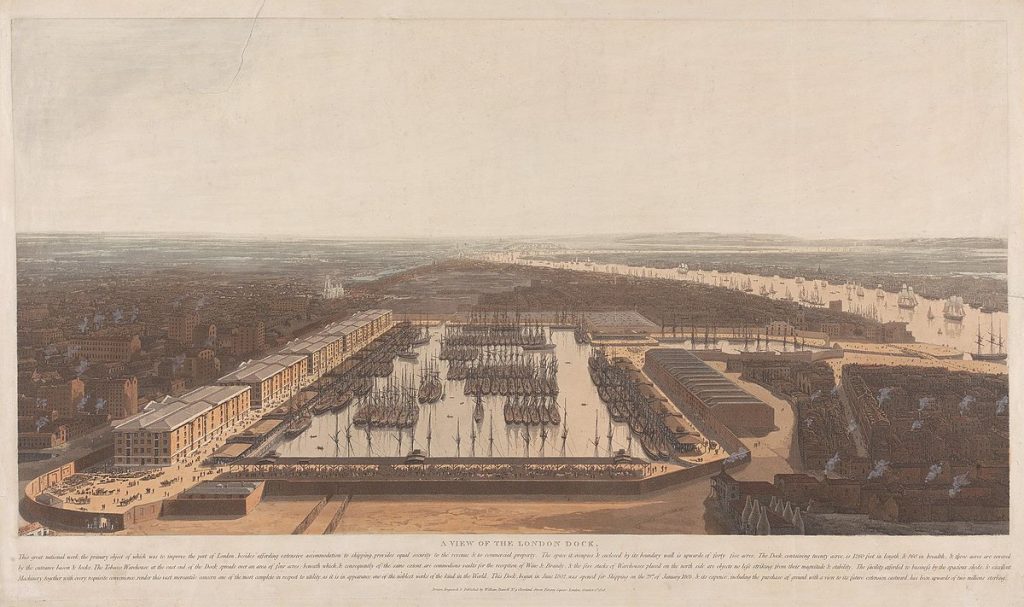

A View of the London Dock, 1808, by William Daniell. Wikimedia Commons. Looking east, this depicts the Western and Wapping basins only, before the eastern section and the Hermitage basin were added. The fine Hawksmoor parish church of St George in the East, off Ratcliffe Highway, towers over its surroundings.

Despite high-value commodities such as wines, spirits and spices landing in quantity in their midst, Wapping and Shadwell were places of great poverty and deprivation. “If the wealthy have their Belgrave-square and their Park-lane,” observed the Atlas in July 1841, “so the poor have their Seven Dials and their Ratcliffe Highway.” A report of the Poor Law Commissioners in 1838 described some dreadfully filthy, overcrowded and fever-inducing housing conditions in the locality. In 1842, a method for finding the time of high water there was flippantly presented as being: “Take a cheap lodging in a cellar in Ratcliffe-highway. When the rats run out of their holes and over your bed, then the tide is rising; but when the flounders get into your pillow-case, and the bed is gently floated up until your nose touches the ceiling, then it is high water.” (Atlas 24/7/1841; Kendal Mercury, from the Morning Chronicle 28/7/1838; Argus, from Punch’s Almanac, 31/12/1842).

Such conditions did not deter the on-shore seafarer, however. “Ratcliffe Highway and Shadwell,” noted The Naval & Military Gazette on 30th June 1838, “are as attractive to the seaman as Almack’s to the beau-monde.” (Almack’s was a high-class West End club). The article reported that even men paid-off from ships in other ports commonly headed to London to enjoy the particular delights of Ratcliffe Highway. Fifteen pubs were listed in 1842 as trading along there, and there were plenty more in the surrounding alleys and byways. When the freehold of one Ratcliffe Highway pub, the Kettle Drum, was offered for sale in 1841, the house was described as being: “commandingly situated…in a neighbourhood at all times ensuring an extensive and lucrative beer and spirit trade.” (The County Chronicle 16/2/1841).

Prince Regent, circa 1895, Ratcliffe Highway https://pubwiki.co.uk/LondonPubs//StGeorgeEast/PrinceRegentTavern.shtml

The pub is on the right with the overhanging lamp. The photograph gives a good idea of how the street would have looked in the early Nineteenth Century.

On 27th September 1841, the “Amicable Total Abstinence Benefit Society” of catholic teetotallers celebrated an anniversary at its Prince’s Square rooms off Ratcliffe Highway. Their cause was undoubtedly a hard sell thereabouts. In 1843 a “singular scene” was described when a cask of brandy being unloaded from a spirit merchants’ cart in Ratcliffe Highway fell and broke open on the pavement, causing its contents to trickle down towards the London Dock wall. “In an instant after, men, women, and children were seen to rush out of the houses and courts with all sorts of vessels, and commence scooping the spirits from the small pools where a portion of it had remained.” (Cork Examiner 29/9/1841; Woolmer’s Exeter and Plymouth Gazette 14/1/1843).

Under the heading “A RUM CUSTOMER”, London’s Morning Herald reported the following Police Court case on 19th August 1840: “Mr Coley, a licenced victualler in Ratcliffe Highway…complained that Sarah Scholes, a wretched-looking female, whose whole garment consisted of a filthy, ragged stuff gown…on the preceding night came to his house and asked for a glass of the best rum…The prisoner also asked for a piece of lemon to remove the flavour of the rum from her breath, and while the latter was being procured, she tossed off the glass of spirits…the servants from five different public houses in the neighbourhood…all declared the prisoner had had a glass of rum at the house of each of their masters, and had not a farthing to pay for it at either place.” The magistrate discharged the prisoner, saying that hers was a case of private debt, but on leaving the court she made straight for the first public house she came to!

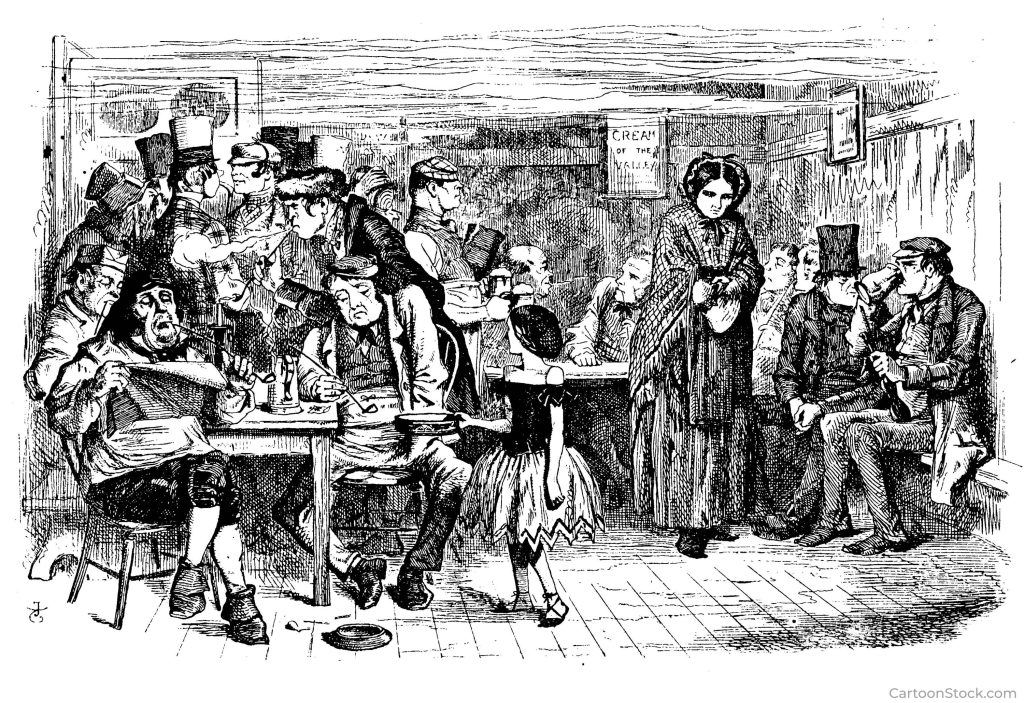

Sir John Tenniel, Victorian pub scene. Cartoon Stock.

In August 1843 a seaman named Richard Hall of the ship Margaret, lying in the Regent’s Canal, near Limehouse, went with a lad from the ship to spend an evening with Hall’s aunt on Ratcliffe Highway. “They called at every public-house on their way, and drank beer, brandy, rum, and gin.” They stayed at the aunt’s house for two hours “still continuing their debauch. Then they left, in the worst stage of drunkenness, in order to return to their ship and [Hall] was last seen alive asking for beer at the Noah’s Ark, which was refused him.” There was a splash, and shortly after he was dragged from the Regent’s Canal, and a surgeon “tried for two hours and a half to restore animation, but did not succeed. The inquest’s verdict was “Found Drowned.” (Bell’s Weekly Messenger 26/8/1843).

In January 1846, Robert Clark, a newly paid-off seaman, decided to enliven some leisure time by embarking upon a “Land Cruise”. Already “three sheets in the wind” he found himself outside the Coach and Horses on Ratcliffe Highway at two in the morning. He commandeered one of the vacant cabs standing in front of the pub, got up onto its box and drove it away, with a companion stowed inside. “After various hair-breadth escapades…he came in collision with an upright piece of timber, and the cab was thrown on its beam-ends, the springs broken, the harness torn, and the glass smashed.” Thankfully the horse was uninjured, but the fate of the companion inside the cab was unmentioned. When hauled before Thames Police Court, Clark excused himself as follows: “Why, please yer honour, when I came out of the grog-shop the ship was without a commander, so I took the helm myself, but I had no compass to steer by, and did not understand the navigation of this here coast (Laughter).” Being unable to pay the cabman for the damage, Clark was sent to prison for twenty-one days. (The Westmoreland Gazette 17/1/1846).

The Jolly Sailor, Ratcliffe Highway

https://pubwiki.co.uk/LondonPubs//StGeorgeEast/JollySailor.shtml

The pub is pictured on the left, with the overhanging lamp.

Many sailors would have been less than jolly after Ratcliffe Highway nights out. In August 1844, three women “of infamous character, who have frequently been in custody for stripping the homeward-bounders of their property” appeared at Thames Police Court charged with stealing a ten-pound note and five sovereigns from John Cooper, a seaman. The latter, “a sun-dried, jolly looking tar”, was paid-off from the ship True Briton, following which he “sallied out upon a cruise, and stopped out all night, and about five o’clock that morning he fell in with the prisoners in a coffee-shop in Ratcliffe Highway.” They proceeded to a couple of pubs where he treated them to various drinks. “By that time he was pretty well slewed…and he was invited to go home with the women [whereon] they all turned into bed together (Laughter). He awoke to find the prisoners gone, and a crown coin “was all the money which the land-sharks had left him.” (Weekly Dispatch 4/8/1844).

Catherine Fitzgibbon, alias “Irish Kit”, was brought before Thames Police Court in April 1849 charged with stealing seven five-pound notes from Richard Cochran, just paid-off from a man-of-war at Plymouth. According to Cochran’s account, he “was strolling through Ratcliffe Highway on Friday night, when the prisoner, insisting that she was an old acquaintance of his, dragged him by the collar into a house in Bluegate-fields, [a notorious Shadwell slum, off Ratcliffe Highway] “and after having compelled him to send out for gin, forced him to pass the night with her. On awaking in the morning he found that Irish Kit had flown”. So had his bank notes, even though he had stitched them into his pocket for security. Irish Kit was arrested at the Angel pub in Shadwell, but only one of his five bank notes, which Cochran said “constituted the greater part of four years’ hard earnings” was still in her possession. (The Standard 6/4/1849).

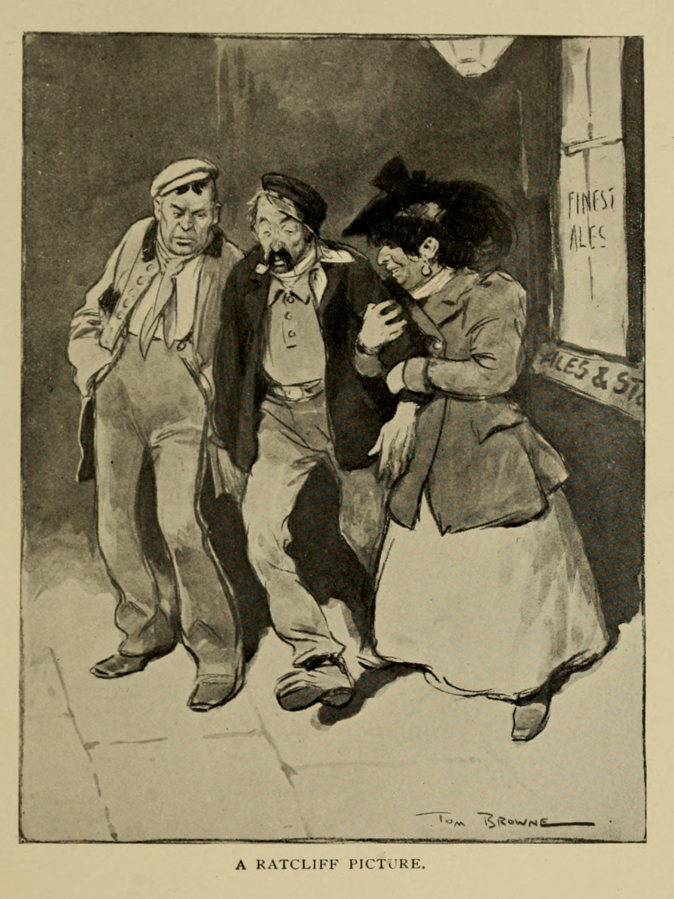

A Ratcliffe Picture, 1910. Wikimedia Commons. A drunk ship’s stoker about to be mugged by a low prostitute and her bully.

A variation on the theme occurred a couple of months after Cochran’s encounter with Irish Kit. Beneath a heading “JACK AMONG THE PIRATES”, a Thames Police Court case was described wherein three women were charged with stealing a silver whistle from James Greene, boatswain to the ship Blenheim. Greene, “a jolly looking tar, stated that he fell in with the prisoners the previous night in the latitude of Ratcliffe Highway, where they took him in tow, and whilst drifting smoothly along under their convoy, having no suspicion that he had fallen in with pirates in petticoats, [one of them] snatched his ‘call’ from his pocket, and scudded away with all her canvas, while her consorts threw their grappling-irons aboard him, and held him fast alongside.” How he escaped and brought the miscreants before the magistrate is not reported. (Monmouthshire Merlin 16/6/1849).

Sailors were not the only targets for theft. In March 1842, a gang of teenage robbers were caught stealing from a linen-drapers shop window in Ratcliffe Highway. The shopkeeper had lodged a complaint with the local police about their persistent depredations. This led to William Argent, an officer of H division, being sent out one night to catch them at it. “To accomplish this he dressed himself like a sailor, and kept staggering along on the opposite side of the street as if drunk.” He observed the gang appear, remove a section of glass from the linen-drapers window (“starring the glaze” in the local vernacular) and remove a bundle of handkerchiefs. Argent seized one of the lads, and the rest were taken soon after at their lodgings. But shopkeepers could themselves be offenders. A few months later, eight Ratcliffe Highway retailers of assorted trades were fined at Lambeth Street Police Court for using false weights and scales. (Evening Mail 25/3/1842; The Oxford University, City, And County Herald 30/7/1842).

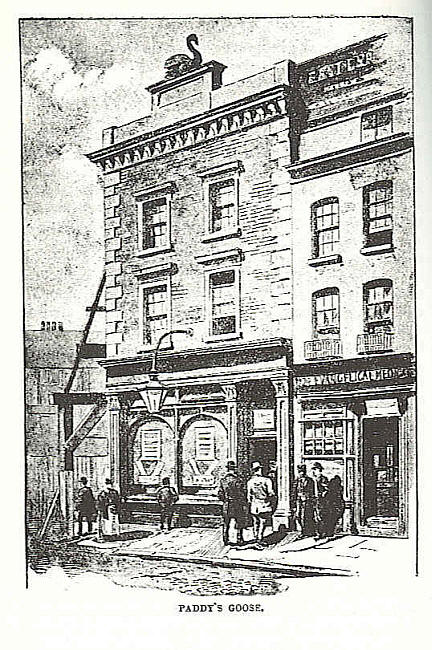

The White Swan, alias Paddy’s Goose, Ratcliffe Highway

https://pubwiki.co.uk/LondonPubs//StGeorgeEast/WhiteSwanGeorge.shtml

Cases of violent, often alcohol-fuelled, disorder came regularly before local magistrates. A man named Francis Carney was convicted of aggravated assault against a young woman, Mary Ann Jones, for having struck her over the head with a poker when they had “quarrelled about some trifling matter” in a Ratcliffe Highway pub. He was sentenced to twelve months in the House of Correction. Thomas Canniffe, a blind fiddler, was committed to Newgate to stand trial for manslaughter against a labourer, Richard Fleming, during a fight over beer money at the Hoop & Grapes, Ratcliffe Highway. Apparently “death had been caused by the rupture of one of the intestines produced by external violence.” On the same day in 1840, Dan Driscoll, “a tall, ferocious looking fellow”, was committed to prison for a violent rampage, commencing next to a pawnbrokers at the New Crane river stairs, off Wapping High Street, during which he assaulted multiple police officers, inflicting a serious injury upon one before he was wrestled into custody. (The Globe 18/5/1842; The Magnet 4/5/1840).

Deaths resulting from violence were not infrequent in the area. The notorious “Ratcliffe Highway Murders”, in 1811, are amply covered elsewhere so need not be rehashed here. Thirty years later, in the Shadwell slum of Bluegate Fields, referred to earlier in connection with “Irish Kit”, two young women named Mary Long, alias Owen, and Hannah Sparks, alias Covington, alias Carrington, launched a “brutal” drunken attack on an old gentleman named Thomas Briggs “with such ferocity that he died a few minutes afterwards”. He was a local property landlord and Long sought revenge on him for distraing upon her mother’s goods for rent. The trial judge directed the jury that the inquest’s finding of “wilful murder” could not be sustained, and, after a verdict of manslaughter, sentenced the pair to only six months hard labour in the House of Correction “to the astonishment of all present.” Carrington, whose criminal career subsequently blossomed further, got her comeuppance in 1843, however, when she was sentenced to ten years transportation for theft. (The Standard 28/6/1841; The Globe 2/7/1841; The Weekly Chronicle 10/7/1841; The Oxford University, City, and County Herald 7/1/1843; Bell’s Weekly Messenger 7/1/1843).

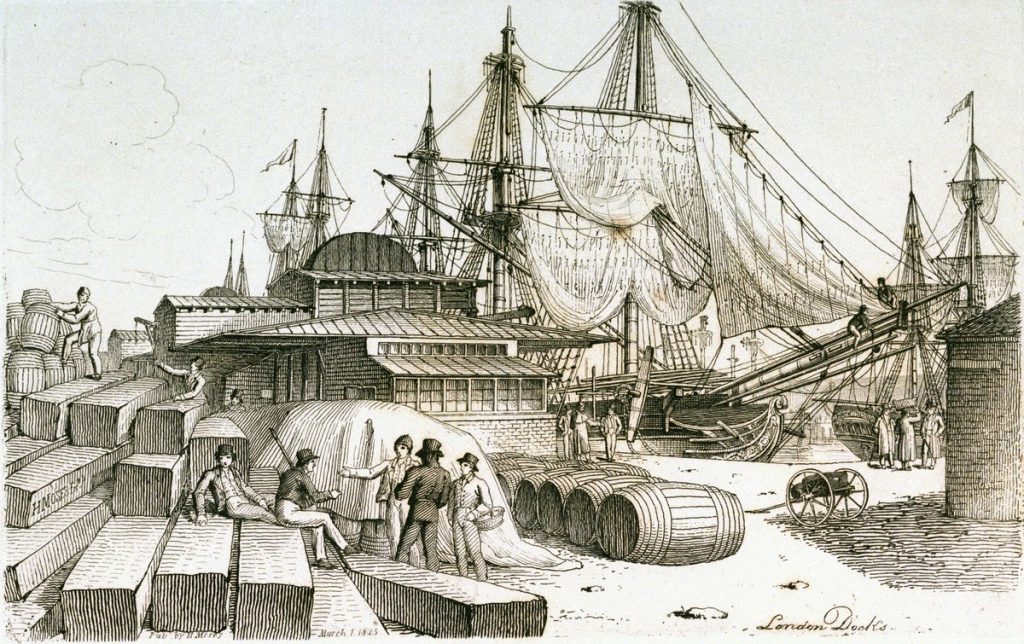

London Docks by Henry Moses, from “Sketches of Shipping”, 1825. Wikimedia Commons. A timber wharf in the London Docks, adjacent to a lock entrance.

Not all cases coming before local magistrates involved robbery or violence, and the district was not without its gentle entertainments. In February 1849 eleven persons were charged at Thames Police Court with “representing dramatic pieces without licence” at 159 Ratcliffe Highway. The parties consisted of the theatrical manager, his wife and daughter, and assorted musicians and players who made up the company. Appearing too before the magistrate was their performing dog, which was “also in custody.” A police superintendent had visited the house one evening and paid his penny for admission. He stated that “The place was occupied by men, women, and children of the humblest class, and a sort of drama was performed, intermingled with dancing and singing.” He did not venture to say whether he had liked it or not. A lawyer who was present, Mr Pelham, “seeing the company completely crestfallen, undertook to plead for them.” He argued that “The performances comprised nothing offensive, and, as far as public morality was concerned, it was surely better to have persons enjoying themselves, and…indulging the imaginative powers at such a place, than indulging in the low debaucheries which other resorts in the same neighbourhood encouraged.” Nominal fines were issued by the sympathetic magistrate, and the company was allowed to keep its stage paraphernalia, including the performing dog. (The Era, 18/2/1849).

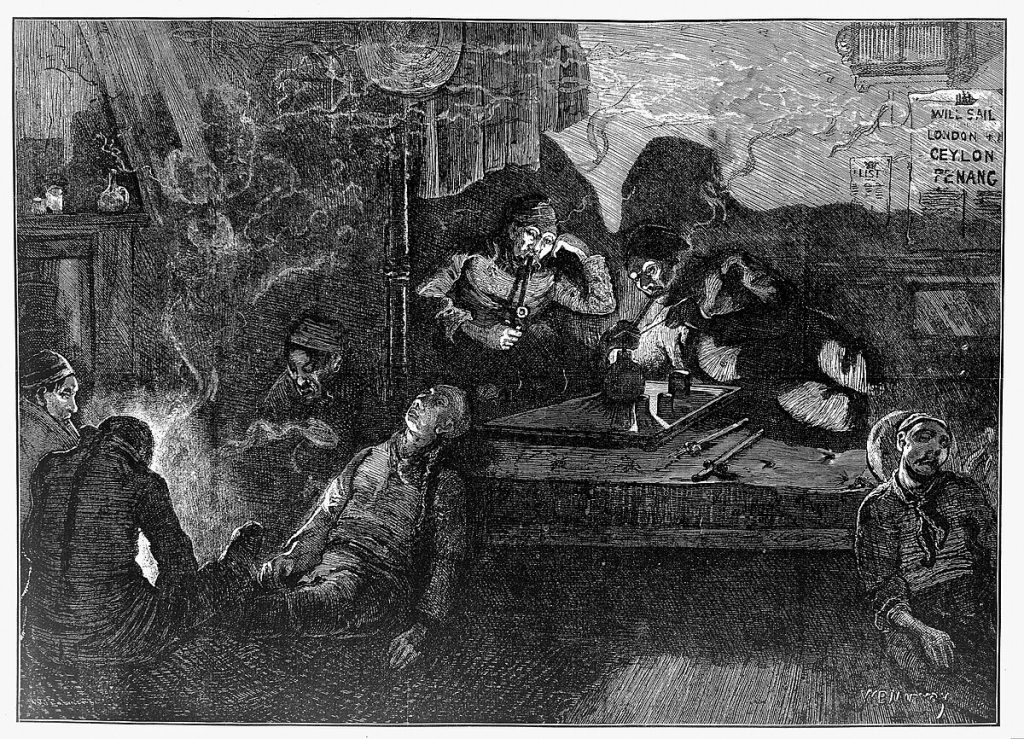

Opium den in the East End of London. Illustrated London News 1st August 1874. Wikimedia Commons.

The area offered other, non-theatrical, attractions. Opium dens are commonly associated with the East End in the popular mind, but it was apparently not necessary to patronise one in order to obtain the drug. In June 1840, William Cocks, a 38-year-old man who was singing and playing piano at a Ratcliffe Highway pub to earn his living, “killed himself …by chewing a large quantity of opium. He was in the habit of taking laudanum; but not having his phial with him, on that evening, he sent for a pennyworth of opium to a druggist’s shop. A woman in the shop sold the quantity asked for, and the pianoforte-player put it into his mouth and kept it there (while he began to sing and play a song entitled “The Wolf”) till he fell down in a stupor. The stomach-pump was applied in vain.” The inquest jury ascribed his death to opium, but did not find that he had swallowed it with the intention of taking his own life. (Dublin Morning Register 1/6/1840, from the The Spectator; The Examiner 7/6/1840).

James Parkhurst, “a young man of respectable appearance and pleasing manners”, residing at a sailors’ lodging house on Ratcliffe Highway, was found dead in his room a few years later of a suspected laudanum overdose. Strangely, “His manners were so superior to the other inmates, and his habits also differing so widely from them, that many conjectures were formed as to the cause of taking up his quarters in a place so humble.” He had apparently disclosed to fellow residents that, “his father was a man of considerable affluence, and residing in splendid style in the vicinity of Blackheath: that he himself had been brought up as a gentleman…and that his only motive for going to reside in that part of the town was an unconquerable attachment to a female named Brazier, who was a pauper inmate of Wapping workhouse.” It would be fascinating to know more of this man’s story. (Yorkshire Gazette 19/10/1844).

London Docks by Henry Moses, from “Sketches of Shipping”, 1825. Wikimedia Commons.

A young woman named Sarah Jackson, charged in 1844 with “attempting self-destruction by taking laudanum, and then endeavouring to throw herself into the Hermitage-basin of the London Dock”, had bought three-pennyworth of the drug from a shop in Ratcliffe Highway. She had been saved by a young man “of colour” who “caught hold of her clothes just as she was in the act of falling into the basin,” and who had earlier attempted to prevent her being sold laudanum. The magistrate expressed surprise that she had been sold the drug, but hers was not an isolated case. (The Patriot 30/9/1844).

London Docks by Henry Moses, from “Sketches of Shipping”, 1825. Wikimedia Commons.

Attempted suicides by drowning, like Sarah Jackson’s, were regularly reported. A number of attempts took place off the swing bridge that carried Old Gravel Lane (now renamed Wapping Lane) across the canal linking the Eastern Dock with the Tobacco Dock. In May 1842, “a woman named Dodds…in a fit of despair and heated by liquor, threw herself over the swing-bridge in Old Gravel-lane, Wapping. A large crowd of persons soon collected…She was sinking for the third time, and in an almost lifeless state, when the alarm attracted the attention of a Scotch seaman, named Archibald MacDonald, belonging to the Robert of London, who instantly jumped from the ship’s side, and after many efforts succeeded in rescuing the female…So pleased were the spectators with the gallant conduct of MacDonald that they subscribed their pence, six-pences, and shillings, for his benefit.” (The Morning Post 18/5/1842).

An unknown female jumped off the very same swing bridge in December 1842, but was not saved despite an alarm being raised. The water was dragged for her body, which was removed to “the dead house” of St. George in the East. Her description was given as follows: “The deceased is a fine young woman, about twenty years of age, fair complexion, and light hair. She was dressed in a halfmourning gown, shawl pattern cape, Tuscan bonnet, low leather shoes, brown jean stays, and appears to be about five feet three inches in height. No money was found upon the deceased, or any article by which her friends might be traced.” Judging by her costume she does not appear to have been destitute, despite the lack of money upon her. The halfmourning gown (worn with a little colour allowed, after full-mourning black) perhaps indicates bereavement as a cause for suicide? (The Planet 18/12/1842).

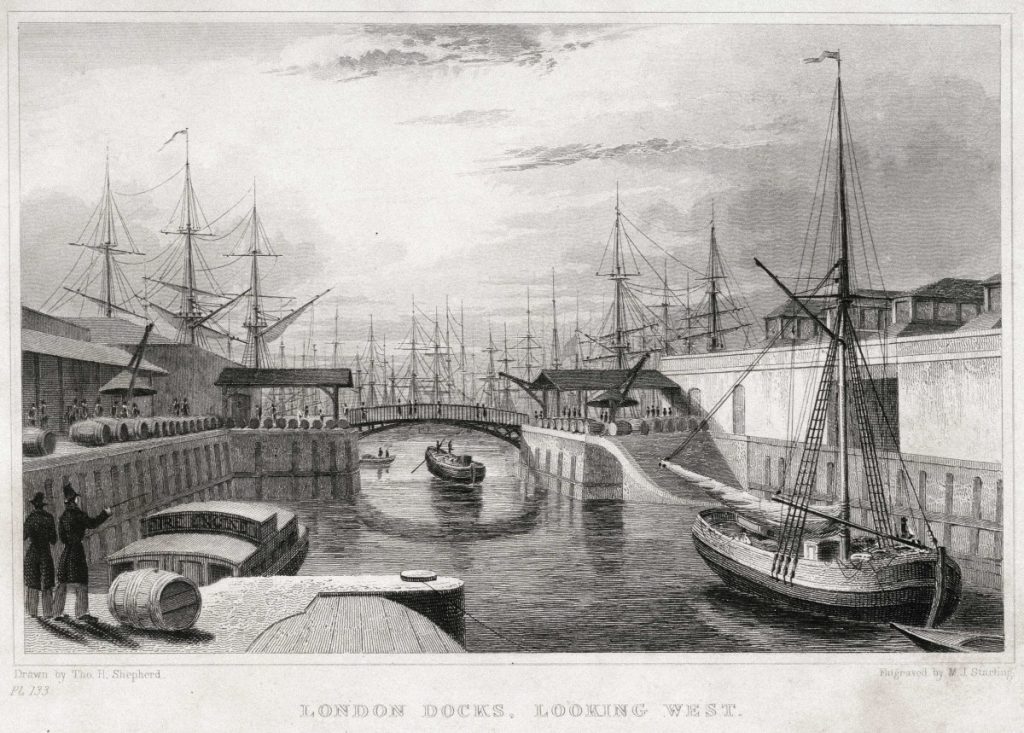

London Docks, Looking West, by Thomas Hosmer Shepherd, 1831. Wikimedia Commons.

The above illustration, and my photograph below, look westward from the Old Gravel Lane swing bridge, site of the above tragedies, separated by an interval of almost two centuries. The Tobacco Dock is in the foreground, and the tops of the tobacco warehouses appear in both views to the right, as does the footbridge straight ahead in the middle distance at the entrance of what was the Western Dock. The former warehouses to the left have been replaced by a gated residential development in my later view, and the tall masts in the now filled-in Western Dock have been replaced by taller buildings. The Shard, over the river at London Bridge, rises in the distance in my photograph.

London Docks, Looking West, 2025. Author’s photograph.

Bodies perennially ended-up in the dock basins or the river. In October 1839 the steamers Sir George Hawk and William Simerton were moored alongside each other in the river, off Pelican Stairs, Wapping Wall, when James Gayzer, a sixteen-year-old sailor boy, slipped when passing from the paddle box of one to the other and fell in to drown. In February 1840 the body of James Newburn, master of the collier brig Ann, of Sunderland, was found in the mud off Bell Wharf Stairs, Shadwell, with a severe bruise on the back of his head and only five farthings of the £20 he was known to have had when last seen alive. In May 1842 an unknown middle-aged man, in a thick brown “Petersham” coat with a velvet collar, tried to leap from a Greenwich steam ferry to the landing stage at Tunnel Pier, Wapping High Street, after the gangway had been lifted and the steamer had pushed-off. He fell in and was drowned. (The Planet 3/10/1839, 22/5/1842; Bell’s Weekly Messenger 2/2/1840).

The Prospect of Whitby, Wapping, 2021. Wikimedia Commons. This pub was known as the Pelican until the late Eighteenth Century when it was rebuilt. Pelican Stairs leading down to the river, where the boy James Gayzer met his end, are signposted to the right.

Numerous narrow stairs accessed the Thames all along the Wapping and Shadwell shorelines, and via the docks and the river these districts were connected to the seas and oceans of the world. The principal bulk goods landed at London Docks, being tobacco, tea, timber, rice, sugar, wines, spirits and spices, meant that they welcomed ships from all over the globe. On one Saturday in 1845, chosen fairly randomly, twenty ships were hauled-in (with capstan and ropes), having arrived variously from Aveiro, Bordeaux, Calcutta, Ceylon, China, Faro, Havana, Madeira, Mauritius, Palermo, Port Adelaide, Puerto Rico, Rio Grande, St. Vincent’s and Sydney. On the same day, ships were hauled-out for Cadiz, China, and Hudson’s Bay. Over one, or two hundred ships might be lying in the docks at any given time. (The Public Ledger 7/6/1845).

The ship Hindostan, which got in on the above-mentioned Saturday from China, brought with it a pair of “Wou-wou”, or Long-armed Gibbon, apparently the first to reach these shores, and named Wou-wou after their distinctive and penetrating cry. “A number of persons desirous of making the acquaintance of these very curious aborigines of the Celestial Empire were congregated to witness their disembarkation and removal to the residence of Mr. J. Warwick, the late superintendent of the Surrey Zoological Gardens, by whom they have been purchased.” His next-door neighbours may not have been as keen to make the noisy wou-wous’ acquaintance. (The St. James’s Chronicle 10/6/1845).

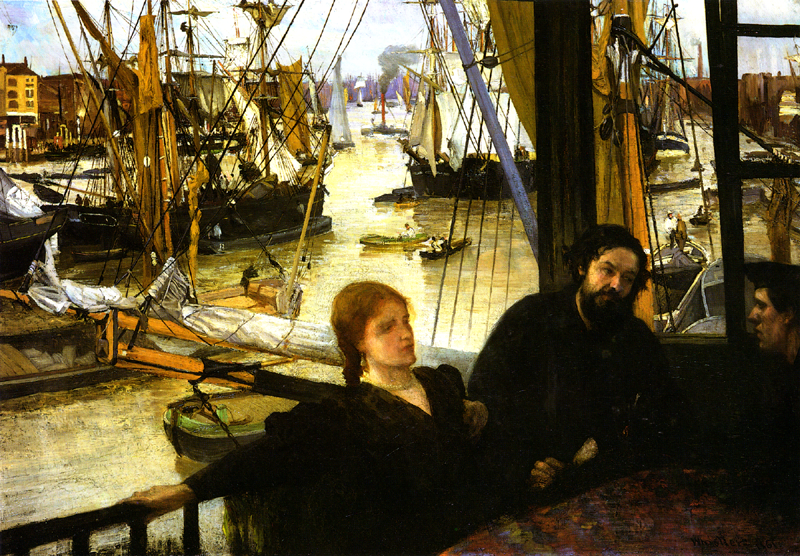

Wapping on Thames, by James McNeill Whistler, 1860-64. Wikimedia Commons.

Human primates embarked at the docks for far-flung voyages. On 17th June 1845, “The splendid fast-sailing clipper Brig TITANIA” was loading there for Hong Kong. “This fine vessel being well armed, offers a desirable opportunity for the transmission of specie, [bullion] and has good accommodation for passengers.” Also loading that day was the DIAMOND, for Calcutta, “This fine vessel has a handsome poop, with beautiful accommodation for the comfort and convenience of passengers.” Regular monthly sailings were scheduled for places as far apart as Australia and Madeira. “The brig GRACE DARLING…will sail again in July [for Madeira] Fare £20, including provisions, wine, bedding, &c., children and servants, half price.” (Shipping & Mercantile Gazette 10/6/1845, 17/6/1845).

London Docks by Henry Moses, from “Sketches of Shipping”, 1825. Wikimedia Commons. The darkly dressed figure in back view in the central group is probably a customs officer.

Despite being surrounded by stout dock walls and gates, ships lying there still fell prey to intruders. One Saturday night in October 1839 the Fortitude, captained by John Fowle, was left unprotected in the Eastern Dock basin. “The burglars effected an entrance…by getting down the skylight on deck, and obtained admission to the state room, where they broke open one of the side cabins and forced in the panel of a locker, in which was deposited a chest of silver plate worth nearly £100, belonging to the captain. The plate chest was forced, and every article it contained, except a soup ladle and two gravy spoons, were stolen. The thieves also carried off a check for £30, a towel marked ‘J. Fowle’, a pair of trousers and some other articles.” It was speculated that, “The robbery must have been effected by some persons well acquainted with the ship, which ought not to have been left without someone in charge.” (The Planet 13/10/1839).

The vast quantities of valuable goods held in 20 warehouses, 18 sheds and 17 vaults, also presented a temptation to abuse. The Tobacco Dock warehouse covered five acres, while the tea warehouse was capable of holding 120,000 chests. The wine vaults, “An underground storehouse for bonded liquors, arched with bricks and extending over more than twenty acres,” were the largest in the world. “Stored up in these vaults there are said to be 65,000 pipes [large wooden casks] of wine – as much as would fill London drunk.” Curious citizens could explore the wine vaults by appointment, as did the assistant relieving (poor law) officer of Marylebone parish with a friend in February 1854. The outraged Christian News reported that he had been dismissed for “appearing drunk” after this “dangerous visit”, as well he might. (Black’s International Exhibition Guide to London 1862 pp. 249-50; The Stirling Observer 23/10/1851; The Christian News 18/2/1854).

London Docks by Henry Moses, from “Sketches of Shipping”, 1825. Wikimedia Commons.

In fact, as Black’s 1862 London Guide stated, “The liability to loss by the fraudulent dealing of persons who have access to the wine vaults is very great.” A bizarre instance of this occurred in 1854 in what became known as the “Osborn Fraud”. This “consisted in twenty-two pipes of Italian or Spanish red wine purchased at the rummage sales, and being deposited in the east vault, changing in a peculiar manner into a very excellent port wine. The Dock Company said that the fraud had been effected…by getting rid of the wine from Osborn’s casks by some undiscovered means, and filling them up by pilfering from good port wine casks.” This “miraculous transformation” considerably enhanced the value of Osborn’s casks, and its discovery resulted in the discharge from the company’s employ of all the coopers then working in the east vault. The case was quoted in the press in connection with a later one (Morgan v The London Dock Company) in which a reverse transformation, from good wine to bad, was alleged to have occurred! (The Weekly Chronicle 20/1/1855; Saunders’s News-Letter And Daily Advertiser 23/2/1860; The Globe 23/2/1860).

If anyone reading this knows whether the underground vaults still exist, I would love to hear about it. Above ground, only fragments now remain of London Docks and their surrounds which once constituted a great trading port in their own right. Ratcliffe Highway, now just “The Highway”, is a rather dismal dual carriageway, largely denuded of its old buildings, and with no pubs or shops remaining in business save for a petrol station and a couple of drive-in fast-food outlets. The Shadwell basin remains, as does the Hermitage basin and a canal through the old Tobacco Dock, but the main Eastern and Western Docks, and the Wapping entrance basin, have all been filled-in. Where there is still water, wild fowl nest here and there in place of ships. There are some wonderful warehouse buildings and several good pubs along Wapping High Street and Wapping Wall. This neighbourhood has a rather quiet village-like feel nowadays, in contrast to the loud tumult of commerce that would once have prevailed. I think it would be a pleasant place to live, if one could afford the extravagant property prices.

St George in the East, taken from The Highway, 2025. Author’s photograph.

Old Rose, Ratcliffe Highway, circa 1920s. https://pubwiki.co.uk/LondonPubs//StGeorgeEast/OldRose.shtml

The only pub building remaining on The Highway. Now long derelict.

The Western Basin South Quay, 2025. Author’s photograph. This surviving quay overlooks the housing development built in the now filled-in dock, with a small canal remaining. The northern part of the former dock is now largely high-rise buildings, with development continuing.

The now filled-in Wapping entrance channel to the docks, with some surviving Regency housing. Author’s photograph.

Wonderfulhistory and recollection of its vibrant and sometimes dangerous past..

Another brilliant blog Mr Croft!

Fascinating. I’d heard of the Ratcliffe Highway murders and this article puts them into context. A very interesting visit to the past.