The Leylands has long since vanished as a distinct area of north Leeds, but it was once a densely-populated and vibrant district, lent extra colour by an influx of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe fleeing persecution in the late Nineteenth Century. Life in the district was pretty harsh in that period, as I shall describe in this post, but I shall also record some strong pointers towards its peoples’ future advancement and their eventual escape from the ghetto.

Just Landed. Immigrant Jews arriving in Spitalfields, East London, 1901

Though there had been prior Jewish settlement in Britain, it was the anti-Jewish pogroms in Russia unleashed by the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881 that incited a mass migration. Perhaps 120,000 Jewish immigrants settled in Britain between 1870 and 1914, mostly after the assassination. Many of those who landed by sea in Hull came from the province of Kovno, in present-day Lithuania, and proceeded by rail to Leeds where there was already an established Jewish community in the Leylands. This ethnic population swelled to about 12,000 persons by 1900.

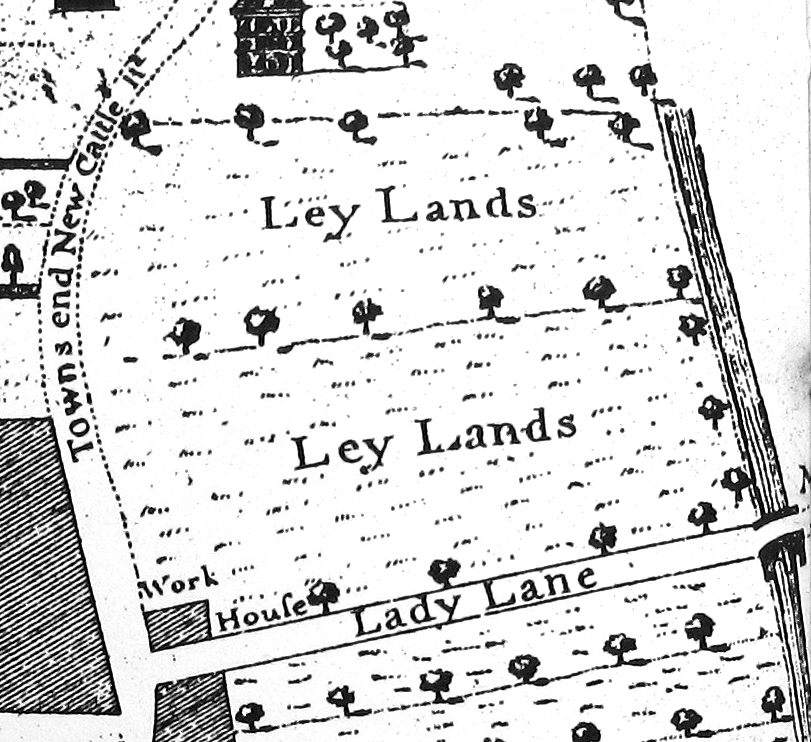

“The Leylands”, old English “Meadowlands” according to the The Leeds Times, was a suburb of “about three-quarters of a square mile”, bounded by North Street to the west, Lady Beck running alongside Mabgate to the east, Lady Lane to the south and Skinner Lane to the north. Its principal thoroughfares were Bridge Street and Regent Street, then crossed by a lattice of smaller streets packed with workshops and back-to-back terraced housing. Almost none of this now remains, and a sizeable southern section of the Leylands’ former extent has disappeared under the car park north of Lady Lane and a stretch of the Inner Ring Road. (The Leeds Times 12/5/1888)

Detail from the 1726 map of John Cossins “Plan of the Town of Leeds”. By the late Nineteenth Century the road on the left had become North Street, the first section of which is now part of Vicar Lane. Lady Beck flows on the right.

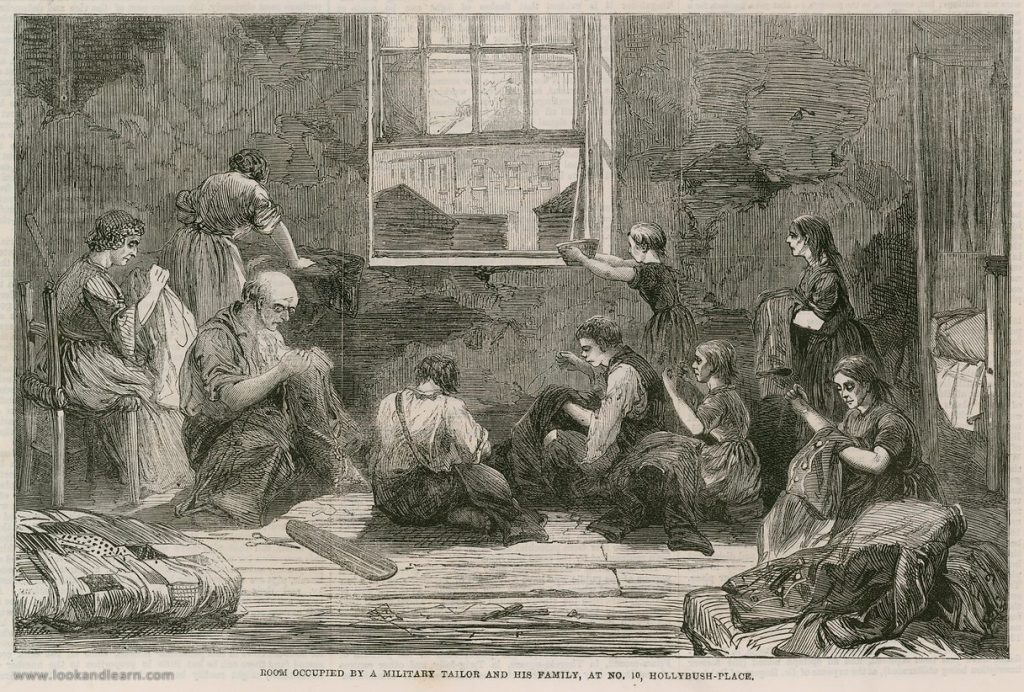

Leeds pioneered the growth of ready-made, rather than bespoke, tailoring from the mid-Nineteenth Century onwards, much of which was undertaken at large mills in the Leylands where cloth was manufactured in bulk. But these were supplemented by numerous smaller Leylands workshops employing “outworkers”, the growth of which went hand-in-hand with Jewish settlement there. These workshops (or “sweatshops”) were largely Jewish owned, and their middlemen would collect jobs of work in bulk from the factories. Minute specialism was the name-of-the-game, with different hours and rates of pay allocated to those such as “fixers”, “machinists”, “pressers-off”, “fellers”, “button-sowers-on” and “basters”. (The Leeds Mercury 21/8/1888)

A reporter observed: “There are not a few places in the Leylands where the conditions under which the workers pursue their calling are visibly depressing. In several streets the basements of the houses are tenanted by families engaged in machining, finishing, and pressing off wearing apparel, and in such places the modicum of daylight which is vouchsafed to the subterranean occupants comes through a few square feet of glass, protected by an iron grating from the feet of the careless pedestrian on the pavement above. In these apartments the ceiling is almost level with the footpath, and the contiguity of street drains is unpleasantly manifest by the painful streaks of damp on the walls.” At one house, three children and two women were seated in a kitchen “stitching with astonishing application in the dim light of a solitary lamp…the odour of the place was oppressive in the extreme. Merely raising their heads for an instant to glance at the visitor, the workers went on plying their needles in silence.” (The Leeds Mercury 17/3/1888)

Room Occupied By A Military Tailor And His Family, At No 10, Hollybush Place. This illustration, reproduced from The Illustrated London News of 24th October 1863, depicts a sweatshop room at Bethnal Green in London’s East End. Credit: Look and Learn / Peter Jackson Collection

But by no means all residents of the Leylands were Jewish, and tailoring was far from being the only industry sited there. The area also hosted two big iron foundries (Smithfield Iron Works and the Hope Foundry), malthouses, breweries, a saw mill, a lead works, a leather works, and numerous boot, shoe, slipper and cabinet making workshops. Crammed into an area of less than one square mile, cheek-by-jowl with domestic housing, these industries would have generated a cloud of effluent that combined with household coal-smoke to make for a noxious atmosphere. And the fact that the land dipped down on both sides towards the Lady Beck, must have caused pollutants to gather there.

Sanitary conditions were equally obnoxious. The Leeds Times journalist “The Owl” wrote of “the sickening odour” of the Leylands “arising from the gullies and sewers” and stated that, “The difference in purity of atmosphere between these low-lying quarters and Woodhouse-lane and the westerly end of the borough is very noticeable.” He further classified the locality as one of the city’s “pest places” where the “poisonous and foggy atmosphere…induces habits of tippling ‘to keep the spirits up by pouring spirits down’ ”. Dr Goldie, medical officer for the borough, cited Templar Court in The Leylands as a “dark spot…where the people are thickly huddled in wretched domiciles.” And a correspondent complained to The Yorkshire Post of: “ashpits overflowing on to the road…and welling up…through trap doors in the pavement”. (The Leeds Times 15/9/1883, 10/11/1883, 30/7/1887; The Yorkshire Post 11/2/1887)

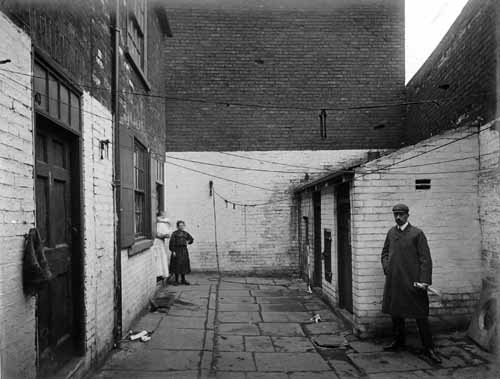

Bridge Court, off Bridge Street. Dense, insanitary housing, between Trafalgar Street and Nile Street, with only ashpits for toilets. By kind permission of Leeds Libraries, www.leodis.net

Alongside poverty and desperate living conditions went drunkenness, violence and crime. A local couple were sentenced to twelve months imprisonment each with hard labour for violently robbing a homeward-bound cloth dresser on Regent Street in May 1881. One Saturday night later that year two policemen patrolling Bell Street, off Regent Street, found a general drunken disturbance underway, wherein “Pots and pans were thrown about the street,” one of the officers being struck “on the mouth, making it bleed” in the affray. Two officers who tried to arrest a drunken riveter, on Mason Street off Regent Street in 1883, were “very severely handled” by him and a crowd, including his wife and mother-in-law, that violently sought to free him from custody, one officer having a tooth knocked out. (The Yorkshire Post And Leeds Intelligencer 6/5/1881; The Leeds Times 8/10/1881; The Leeds Mercury 6/10/1883)

Bell Street, off Regent Street. Looking west to the back of Star Street. Two police officers encountered a drunken affray here in 1881. By kind permission of Leeds Libraries, www.leodis.net

Some incidents were rather more comic. A workhouse pauper named Thomas Hobson, afflicted with the “green eyed monster” of jealousy, attacked a man in 1882 for “messing” with his woman and complained that “She took my money and went to the Leylands to drink it with other people.” Convicted of assault, Hobson was offered to be bound over “in two sureties to keep the peace for three months.” He said he could get no sureties and would serve gaol time instead, at which the reporter quipped that he had perhaps been presented by the magistrate with “Hobson’s choice”. (The Leeds Times 25/3/1882)

Under the headline “A Fool And His Money” it was reported in February 1883 that a soldier, James Clarke of Cannon Street, who had lately served in Afghanistan, was robbed by two women of £4 at a Leylands “house of ill-fame” from a “purse-belt” which he had unaccountably unbuckled from his midriff and failed to keep an eye on. “The women refused to return the ‘brass,’ and the valiant warrior, threatened with violence, left without it.” (The Leeds Times 24/2/1883)

Headed “Wearing Borrowed Plumes”, a 25 year-old “hawker” named James Keeley was reported in 1886 as having been an in-patient at the General Infirmary, and, having been dressed “in shabby habiliments”, was lent a suit of clothes there. “He left the infirmary…without obtaining his proper discharge, and forgot to leave his borrowed clothes behind.” He was later apprehended in the Leylands by a detective officer “while wearing the now-stolen ‘toggery’…He was committed to jail for one month to reflect on the vanity of keeping up appearances.” (The Leeds Times 6/2/1886)

Some incidents were rather more grotesque. In 1885, a 20 year-old Italian organ-grinder named Luigi Solvetta was plying his trade on Regent Street when the son of a passing butcher from Gower Street named Callaghan “annoyed him by dancing around the instrument. Solvetta struck the child, upon which Callaghan said that if he did so again he would strike him. Solvetta thereupon drew from his pocket a knife and savagely plunged the blade of it through Callaghan’s left eye, completely destroying it, and penetrating a considerable distance towards the brain.” (Unfortunately, I have been unable to discover the outcome of this outrage for either victim or perpetrator. The Leeds Times 5/9/1885)

Some incidents betray very different attitudes to those of today. In March 1885, an inquest was held into the death of a new-born male child found in the cistern of a water closet in the back yard of houses in Moscow Street (between Templar and Hope Streets) wrapped in a handkerchief. The coroner found that “death resulted from asphyxia caused by drowning,” and the mother was identified as Sarah Casey, a 23 year-old single woman of Moscow Street, who was indicted for child murder at Leeds Assizes. At trial Casey admitted she had given birth to the child in the outhouse, but said that she left it there, believing it to be dead, and denied she had put it into the water closet. The jury was surely being disingenuous in convicting her of the lesser charge of “concealment of birth” only, and she was sentenced to just one month in gaol. (The Leeds Times 7/3/1885, 25/4/1885, 2/5/1885; The Leeds Mercury 21/3/1885, 28/3/1885; The Yorkshire Post 29/4/1885)

Moscow Street, off Hope Street. Sarah Casey’s dead child was found in one of these outhouses in 1885. By kind permission of Leeds Libraries, www.leodis.net

A near identical case the very next year concerned a new-born female child found dead in an outhouse at Cannon Street, off Regent Street. At trial the eighteen year-old unmarried mother, Grace Ann Cheetham, was convicted of concealment of birth only, despite the inquest jury’s previous finding of manslaughter against her. The judge said he was inclined to discharge her, but, on learning that she was ill and had no home to go to, sentenced her to three weeks imprisonment in the gaol infirmary, so that she might “be placed in a fit state of health to be discharged”. (The Leeds Times 6/2/1886; The Leeds Mercury 20/1/1886, 21/1/1886, 30/1/1886)

Cannon Street. Looking west from Regent Street. Grace Ann Cheetham’s dead baby was found in an outhouse here, in 1886. By kind permission of Leeds Libraries, www.leodis.net

The dead body of yet another baby was found by two nightsoil-men when turning out the midden at No 43 Copenhagen Street, off Bridge Street. in 1892. The inquest found that the child had been born alive and that the death had been owing to “a want of proper attention at birth”, but it seems that the mother was never located in this case. (The Yorkshire Evening Post 18/1/1892, 20/1/1892)

Copenhagen Street. Looking west from Bridge Street up towards North Street, we see a demure group of Jewish children in 1901. By kind permission of Leeds Libraries, www.leodis.net

Leniency unlikely to be matched today was also evident when a woman named Mary Elizabeth Leach (25) was killed in Mason Street, off Regent Street, in 1887. According to their landlady, just after midnight one Saturday night the man with whom Leach was cohabiting, James Pyrah Peate (27), “came to the house the worse for liquor, and went upstairs into the bedroom.” Shortly afterwards the landlady heard screams, and, on going up to investigate, saw Peate strike his paramour full in the face three times. “One of the blows caused her lips to swell, and her nose and mouth bled profusely, the pillow on which she was lying being saturated with blood.” Leach became insensible and died four or five hours later. Peate was found guilty of manslaughter, but was only sentenced to twelve months imprisonment. This apparent injustice was probably due to Leach being described as “a woman of loose character…of an excitable and passionate temperament…very much addicted to insobriety.” (The Leeds Mercury 20/6/1887, 21/6/1887; The Leeds Times 25/6/1887, 2/7/1887; The Yorkshire Post 26/1/1887; The York Herald 6/8/1887)

Regent Street. Mason Street, where James Peate killed Mary Leach, leads off to the right just past the Mason’s Arms in the foreground. Perhaps he had been drinking in this pub on that Saturday night in 1887. By kind permission of Leeds Libraries, www.leodis.net

Another killing had a very different outcome for its perpetrator, 29 year-old Jewish slipper-maker Samuel Harrison (clearly an anglicised surname). At Back Nile Street off Bridge Street in 1890, what came to be described as “The Leylands Tragedy” occurred: “Screams were heard; a window was thrown up and smoke was seen to be issuing from the house.” A passing policeman and a civilian, “broke into the house, and a horrible sight met their gaze. The wife and child were bleeding from severe wounds, which numbered six on the wife…The house furniture had been partially broken up and was scattered about the floor covered with blood, and to this tangled mess Harrison had tried to set fire, casing the smoke which attracted attention.” His wife Dora died from her wounds and Harrison was convicted of murder and sentenced to hang, but was instead committed to Broadmoor on appeal to the Home Secretary. Convincing evidence was adduced that Harrison had been insane since he sustained a severe head injury in his native Poland, where he had been known as “Samuel the Lunatic”. (The Leeds Times 10/5/1890, 17/5/1890, 24/5/1890; The Leeds Mercury 21/5/1890, 15/8/1890; The Yorkshire Post 19/8/1890)

Back Nile Street. Looking west from Bridge Street, scene of “The Leylands Tragedy”. By kind permission of Leeds Libraries, www.leodis.net

It is notable that Harrison’s is one of the few reported cases of criminal violence I have found that was committed by a Jew. They were not, of course, without vice, illegal gambling in the Leylands being one well-documented Jewish pastime. But hostility towards these incomers was itself a shameful aspect of Leylands life at the time. “Where are the police?” The Leeds Times was moved to complain on their behalf in 1886: “The Jews inhabit the Leylands in large numbers. They are generally peaceable, orderly citizens, who respect the law, and demean themselves as becomes respectable members of the community. Some low-bred fellows, ‘roughs’ who ought to be ashamed of their conduct, annoy the Jews in various ways, and should have the kindly attention of the police”. (The Yorkshire Evening Post 7/3/1891, 24/9/1891, 21/1/1895; The Leeds Times 30/1/1886)

And the contemporary press itself was not entirely innocent of perpetuating race hostility. Another whole blog-post could be written exploring this theme, but I will confine myself here, by way of example, to quoting from a letter of complaint written by “A Lover of a Quiet Sunday” to The Yorkshire Post in 1884. “In no place in Europe,” he claimed, “are the Israelites treated so kindly as in England, nor is there any other country where where they can earn the same amount of money as among us, and it is a poor return for this hospitality that they should render our Sunday hideous by running their machinery in [an] ostentatious manner…etc.,”. (The Yorkshire Post 12/7/1884)

Jews were unashamedly industrious, and they formed a cohesive and religiously-observant community that saw the education of their children as the surest way out of squalor and disadvantage. “Mir zanen do” one said on arrival, which apparently was Yiddish for “We are here”, and they meant to make the best of it.

Noble Street. Leading north off Hope Street. We see a crowd of remarkably well-shod and turned out Jewish children (also evident at Copenhagen Street, pictured above), especially considering the conditions in which they lived. By kind permission of Leeds Libraries, www.leodis.net

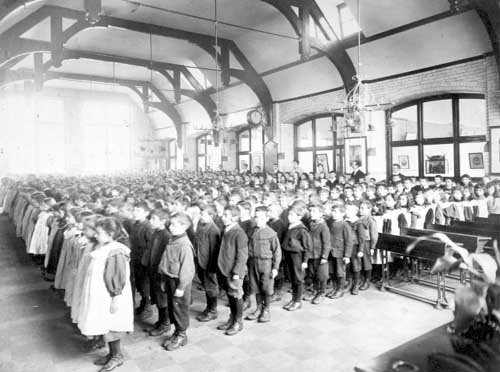

The Leeds Jewish Free School was established in 1881 to provide evening and Sunday instruction for children in Hebrew and religious knowledge, in addition to their regular education at the Leylands Board School on Gower Street or the Board School at Darley Street. These two state schools were stated to be “excellent”, and the Gower street one in particular was reported as having “a striking record of attendance”. Headlined “The Jews’ Appreciation of Education” it was reported in October 1900 that Gower Street had averaged upwards of 99.5 per cent attendance over the previous six months, by which time its pupils were almost exclusively Jewish. A notable achievement for such a deprived area. (The Leeds Times 23/6/1883, 8/1/1884, 2/7/1898; The Leeds Mercury 30/10/1900)

And so the foundations were laid for the early Twentieth Century translation of Jews into the professions and the more salubrious suburbs of North Leeds. Perhaps the foundations were also laid for the future Jewish engagement with Leeds United. In an 1898 win for Darley Street school over Gower Street, both sides deserved “praise for their earnest and vigorous play. Tompofski scored the whole of the three goals for Darley Street, although Ginsberg and Rosen defended well for the Leylands.” (The Yorkshire Evening Post 10/9/1898)

Darley Street Board School. Boys at play. By kind permission of Leeds Libraries, www.leodis.net

Darley Street Board School. Boys and girls enjoying a “Happy Evening” of play with games and toys. By kind permission of Leeds Libraries, www.leodis.net

Darley Street Board School. School Assembly. By kind permission of Leeds Libraries, www.leodis.net

Acknowledgements:

I am grateful to Diane Saunders and Philippa Lester for their splendid book “From The Leylands To Leeds 17: Jewish Leeds in words and images” (2014, Leylands Books, Leeds). Their celebratory spirit informs this blog post.

I am also indebted to Leeds Libraries Local and Family History Service for their invaluable help with maps and for their kind permission to use illustrations. I have reproduced here only a small number of the many historical photographs they have of the Leylands.

Other Sources: “Kelly’s Directory of Leeds”, 1888; “The Leeds Jewish Tailors’ Strikes of 1885 and 1888” by Colin Holmes in Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, vol. 45 (1973) and “Leeds Jews in the 1901 Census: A Demographic Portrait Of An Immigrant Community” by Murray Freedman (2002), both of which articles can be found in The Thoresby Society’s Box 22G5 at The Leeds Library.

Excellent: a very well-researched post. The various stories of Leylands’ life are enhanced by the juxtaposition of photos showing the places where the action took place. As a long-time resident of Leeds, it was great to learn about a part of my city that I hardly knew.

Fascinating to hear about that area of Leeds. I only know North Street but your article brings the area to life. What a huge amount of industry in a small area. Also interesting to consider how hard the Jewish immigrants worked in order to give their children better opportunities.

This is so interesting. My GGGGrandfather was a tailor living in Nile Street in 1841 (census). He was Scottish so no Huguenot interest there but fascinating to see the area where he lived described so vividly.

So interesting reading about the Leylands, Darley Street school… my mother, a milliner by trade grew up in just that area of Stamford Street and used to proudly tell me stories of her childhood including about the sweatshop in the attic where her father, a master tailor and his employees completed the suits.

Thankyou for the insight.