When I lived in London I worked for some time in an office overlooking the Aldwych, off the Strand. I did not know then, as I watched the traffic thunder relentlessly by from an upper-floor window, that this had once been an out-of-the-way area of great charm and character. Around the turn of the nineteenth century twenty-eight acres of closely packed lanes, alleys and courtyards thereabouts were demolished in a grand redevelopment, to be replaced by Kingsway and the Aldwych and to facilitate the widening of the Strand. I was also unaware then that the area once housed the reputedly unholy Holywell Street, notorious in Victorian times for its bookshops where pornography could be found.

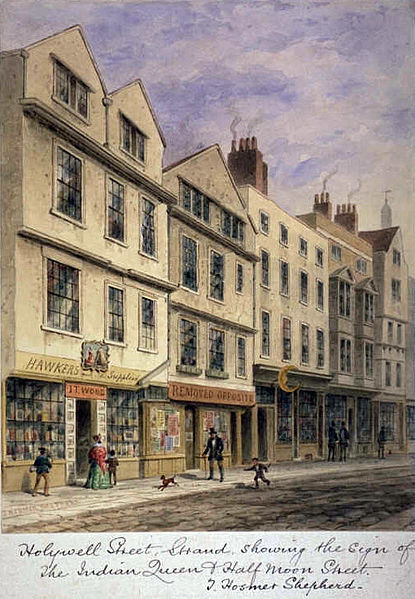

Holywell Street by Thomas Hosmer Shepherd (1793-1864) Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Despite its open appearance in the above illustration, old photographs show the street to have been so narrow as to exclude most wheeled traffic. Like nearby Wych Street, which was also rubbed-out in the grand Edwardian redevelopment, Holywell Street contained a higgledy-piggledy array of quaint old buildings, some of great antiquity.

Though writing long after its demise Michael Sadleir, author of Fanny by Gaslight, penned a vivid portrait of Holywell Street in his novel of London low-life Forlorn Sunset (pp. 410-22, 1947). Sadleir (1888 to 1957) has his luckless antihero, Paul Gladwin, go there for nefarious purposes in November 1878. Gladwin’s “lean stooping figure, wearing a shabby black overcoat and a shapeless slouch hat”, shuffles into the “narrow chasm of Holywell Street”.

Sadleir writes: “A crazy jumble of houses rose on either side. A few of the old timbered buildings, whose upper stories so far overhung that two people could shake hands across the roadway, had survived the Great Fire; a few others, partially destroyed, had been patched and tinkered into some sort of stability…A rag-bag of a street, in fact, and one whose population was as squalid and promiscuous as its architecture…

“More than one huckster made a pitch of Holywell Street. A vendor of comic songs stood and walked and stood again, shouting the titles of his penny sheets, often with humorous gesture or lively comment. A knife-seller had set out his wares on a small square of dirty carpet. Others, with trays slung about their necks, offered studs or glass jewellery or secret nostrums for various and often alarming ailments.

“The ground-floors of the buildings…housed a succession of small shops. The majority were bookshops, print-shops or jumbles of old glass, china and second-hand furniture; but there was also a sprinkling of food and clothing shops, two small auction rooms open to the street, a jeweller (so-called), a barber, and quite half a dozen cigar-shops. At either end stood a flaunting public house.”

After this splendid evocation of a lost world, Sadleir lets himself down somewhat by casting a clichéd Jewish bookseller he calls Mr Jack Bernstein as an under-the-counter pornographer with whom Gladwin has business to transact. “He had the soft, rather pleading eyes of his race, but their quality of gentleness was violently belied by a rasping voice, a large cruel mouth full of very white teeth, and a curious roughness of gesture even when (as occasionally was the case) no roughness was meant. He always wore a billycock hat pulled so far down his head that it rested on his prominent ears, and when he spoke, the traditional lisp and adenoidal blockages were so marked that he was suspected of exaggerating them on purpose.”

The furtive nature of Bernstein’s establishment is conveyed as follows: “It was a single-windowed shop, and a sloping stall on trestles was so placed in front of the window that passers-by…could not approach closely to the window but were constrained to examine from a distance of some three feet whatsoever Mr Bernstein chose to display behind glass.” Appearing therein, hand-bills containing tantalising synopses of certain publications could dimly be made out. Sadleir reproduces several of these, who knows whether from real-life or his own imagination, such as:

“Just out, Price Sixpence, with Illustrations. The New Racy Volume, or the Private Companion of every person above the age of Seventeen”. Or “The Diary, Confessions, and Curious Attractions of a noted favourite and celebrated Quack Doctor, detailing his Amusing Adventures With his Pretty Patients, whose blushes illuminated the whole of the Examination Room.” Or “A Book For The Wicked, or Tit Bits For The Bed Room, Containing Ninety Pages of racy reading and Ten Coloured Cuts of a nature rather going it.”

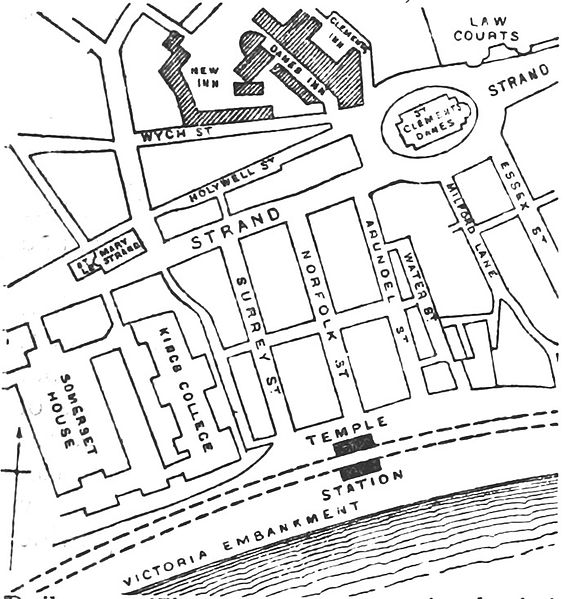

I have no way of knowing how accurate Sadleir’s portrayal of Holywell Street was, especially since it is now entirely subsumed under the buildings, pavement and tarmac of the Strand. It ran parallel to that thoroughfare, just west of St Clement Danes Church (which is still standing, on its own little traffic island), as appears from the following map.

District Map (1888) Temple, Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

It’s difficult to be precise, but the office building I worked in, on what is now the eastern curve of the Aldwych crescent, is probably just about where the law-chambers of the New Inn used to be, as marked on the map. It was a law firm that I worked for there, and if I’d been around a century earlier perhaps I’d have worked at the New Inn. In those days, I would at least have had some fascinating local colour to observe whilst strolling melancholically about in my lunch break.