Leeds is an unlikely place to find a three-thousand year old Egyptian mummy. But the coffin containing the embalmed remains of Nesyamun, a priest of the ancient god Amun, was brought to Leeds in 1823 having been unearthed near Thebes in Egypt. It became the star exhibit in the newly formed Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society’s museum on Park Row (“The Philosophical Hall”) which also housed rooms for the society’s meetings, a hall for lectures and recitals, and an extensive library.

Although his coffin bears an inscription praying for Nesyamun’s freedom of movement in an eternal afterlife, it was probably not anticipated by the tomb-scribes that his soul’s wanderings would bring him to West Yorkshire. His mummified remains, however, have not since been allowed to rest in peace.

Park Row, Leeds, 1882, by Leeds artist John Atkinson Grimshaw. Public domain

The Philosophical Hall, built in 1821 to a neo-classical design by Leeds architect R. D. Chantrell, appears in the left-foreground of Atkinson Grimshaw’s wonderfully moody, and appropriately spooky, evocation of late-Victorian Park Row (above). So successful was the Philosophical and Literary Society, and its museum, that the hall was substantially enlarged and renovated in 1862 by architects Dobson & Chorley, who gave it the impressive porch we see in the painting. The splendid Italian-gothic Beckett’s Bank appears opposite (designed by Sir George Gilbert Scott, who also built the Midland Grand Hotel at St Pancras Station in London).

On visiting Leeds in 1896, The Builder magazine praised Park Row “for its remarkable succession of large and dignified buildings”, adding, “…it is not often that one meets with a modern city street which can show so large a proportion of buildings that are worth notice.” For almost 150 years Park Row was home to the earthly remains of Nesyamun, the “Leeds Mummy”, but, inevitably, few of the street’s buildings “worth notice”, now remain.

By the time of its renovation in the eighteen-sixties, the Philosophical Hall’s museum (according to its historian, E. Kitson Clark) “…was equal, if not superior, to that of any other provincial institution. It comprised 7,000 geological, 1,300 Mineralogical, 6,000 Zoological specimens, and the most remarkable Mummy in the kingdom.”

Other notable exhibits were the skeleton of a female elephant, late of Wombwell’s traveling Menagerie, and those of an Irish elk, an Ichthyosaurus and a Plesiosaurus, plus the stuffed bodies of a young lion, an armadillo and a boa constrictor, also acquired from Wombwell’s. The bones and teeth of a “Great Northern Hippopotamus”, discovered in a brick-yard at Wortley, were featured, as were two skulls of extinct bears, a slab of Breccia with prehistoric flint implements from the Dordogne Valley, and mummies of crocodiles, plus implements and bones from a tumulus on Esketh Moor, near Thirsk. The Archaeological Room displayed a magnificent collection of Greek Marbles, Roman Altars and Querns, together with a tessellated Roman pavement from Isurium (Aldborough, Yorkshire).

Entry was cheap and, “The Museum attracted thousands of visitors, many of whom were in the humbler walk of life, whose decorous conduct…deserved commendation” (presumably their “decorous conduct” was not normally to be relied upon!). A photo of the Zoological Room shows an impressive space well-lit by skylights, with large exhibits in the middle, surrounded by a good many (now terminally old-fashioned) glass display cases at floor level, and a further course of collections running along a gallery above.

It may seem perverse to bomb someone who has already been dead for three-thousand years, but on 15th March 1941 a German air-raid shell exploded in the Philosophical Hall and disturbed Nesyamun’s slumbers. The building’s frontage was destroyed and three floors towards the front collapsed, so that the curator found himself conducting an archaeological dig in the wreckage of his own museum.

Although the glass case surrounding Nesyamun’s coffin was shattered, the coffin and the mummy within were largely undamaged. Rubble was swiftly cleared, exhibits were recovered, and damage done to taxonomic figures (such as that of Mok the Gorilla, late of London zoo) was repaired. Much of the building, and its essential structure, remained intact, so that the museum’s lunch-time music recitals in the lecture hall were resumed after just a few months’ work, and the whole building was reopened by the Lord Mayor in June 1942.

Given this, it is maddening that the Philosophical Hall was closed in 1965, and demolished the year after, to make way for the atrocious HSBC building that now occupies its spot. The hall had been transferred into the ownership of Leeds Corporation in 1921 and that body never properly restored the frontage, settling for a temporary concrete render that gave it a “makeshift appearance” (according to the Yorkshire Post in 1953). The glorious Beckett’s Bank building, opposite, was demolished around the same time to make way for an anonymous NatWest Bank.

Today’s City Museum (including Nesyamun, and the Great Stuffed Bengal Tiger) was opened in the Mechanics Institute building on Cookridge Street in 2008. Good effort though this is, it only displays a tiny fraction of the collections on show in the old building (the rest is in storage), which could claim to be a natural and local history museum of national importance. Also lost is the architectural quality of the Philosophical Hall itself, and its quality as a centre of municipal cultural and intellectual life. Meanwhile Nesyamun slumbers on – indifferently and indestructibly – as the millennia roll past.

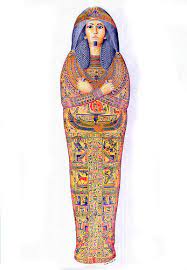

A reconstruction of how the coffin of Nesyamun might originally have appeared. By Tomohawk (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons

Sources:

Books: The History of 100 Years of Life of the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society, E. Kitson Clark (1924); The Coffin of Nesyamun, the “Leeds mummy, Belinda Wassell (2008); Building a Great Victorian City, Leeds Architects and Architecture, 1790-1914; West Yorkshire Architects and Architecture, D. Linstrum (1978).

Newspapers: The Builder, 12/12/1896; Leeds Mercury, 17/12/1862; Yorkshire Evening Post, 27/3/1941, 2/3/1942; Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, 24/3/1941, 28/3/1941, 24/6/1942, 7/7/1941, 3/8/1944, 15/7/1953